As a cartoonist, Jules Feiffer plumbs the depths of the human condition with such fiendish finesse as would put a smile on the most jaded of faces.It’s a gift he discovered early, with the help of his mother, Rhoda, who drew fashion designs that she would go door-to-door selling. And while she introduced him to the joy of Broadway musicals and the finer things in life, of which she somehow felt denied, she also taught him shame and infused their home life with an aura of strict suppression.

“My only escape was a life of escapism: reading comics, going to movies,” he wrote in his memoir “Backing Into Forward,” and immersing himself in the fantasy realities that he saw as his future.

Still, the superhero powers of which he dreamed remained a stretch. Much against his will, he served in the Korean War, then came to Manhattan, living from apartment to apartment and doing “dumb advertising jobs,” as he calls them. He made his mark with the Village Voice strip, “Sick Sick Sick: A Guide to Non-Confident Living,” which became “Feiffer’s Fables” and finally “Feiffer.” Coming of age during the Cold War, a period of American containment that mocked the suppressive atmosphere of his home, his radical politics emerged in his art, as it did in his life.

When his 40-year run at The Voice ended, a world of new opportunities emerged, including a stint with The New York Times—and a call from an old friend, Roger Rosenblatt, who started the writers program at then-Southampton College. That is when Mr. Feiffer discovered the East End, where he has resided full-time for the past eight years.

He lives on a quiet East Hampton street in a house filled with sunlight. At 87, “having aged out of New York,” as he puts it, and realizing that his hearing isn’t as sharp—neither is his walking—he finds he can pursue his love of books far from the madding crowds of Manhattan. His most vital activities now rest in the life of the mind. As perhaps, they always have.

The 1986 winner of the Pulitzer Prize for his Village Voice cartoons and a prolific writer, Mr. Feiffer’s oeuvre extends beyond a dozen or so children’s books and a trilogy of graphic novels—currently in the works—to Obie Award-winning plays and an Academy Award-winning animated short, “Munro.”

In a professional career that spans 70-plus years, he has drawn and written about a huge range of subjects, from the way men and women use each other as objects, from “Carnal Knowledge” to “Passionella,” which was the inspiration for one of the three short plays in the musical “The Apple Tree,” about a chimney sweep who transforms into a Hollywood movie star.

Just five years ago, he published his memoir, “Backing Into Forward,” a literal who’s who of left-wing New Yorkers. Here we meet Hollywood A-listers and New York literati, theater people and artists, among whom lurks a Russian spy, Rudolf Abel, the central character in the movie “Bridge of Spies.”

“Mark Rylance looks exactly like Rudolf Abel or, as I know him, Emil Goldfus,” Mr. Feiffer lights up. “What a movie!”

Struck by the subject of Steven Spielberg’s film—the Cold War—he remarks about the grip it holds on the American psyche. From his perspective, “Our fear of terrorism, whether we call it the Soviet Union or ISIS” is entrenched in our social consciousness.

In opposing that socio-political status quo, he has been outspokenly anti-McCarthyism, anti-“an endless series of wars that last a lifetime,” anti-capitalism and anti those who are simply, for no reason, “anti.” With an ideology, which he describes as “indigenous free-form American radicalism,” he remains the quintessential American satirist.

“What moved me toward satire was this innocence and sense of humor and childlike idealism coming up against life as we all lived it—in my case, during the Great Depression and after,” he said, continuing with a sly grin. “Dealing with grownups who spoke in code put me in perfect shape to be a satirist during the Cold War years.”

In conversation, Mr. Feiffer is loquacious, offering his insights about the artists and intellectuals who inspired him: Mort Sahl, Nichols and May, Lenny Bruce, Edward Albee and Samuel Beckett. Still, the fact that Mr. Feiffer’s work remains so eminently relatable to us today, speaks to its intemporality.

“From time to time, I’ve been fortunate enough to write or draw on things where I represented the reader or the audience,” Mr. Feiffer said, adding that he believes art—his art, in particular—“represents the inarticulate thoughts, or not yet articulate views, that we have. But we don’t have them until someone gives us permission to have them.”

Today, Mr. Feiffer is as innovative and creative as ever. Last year, W.W. Norton published his first graphic novel, “Kill My Mother,” drawn in noir style. Indeed, that was the style of his mentor, cartoonist Will Eisner, for whom he worked starting at age 17. Try, as he had, to paint those dark, grotesque and distorted images like Eisner, he said he never could until he wrote this novel. The second in his trilogy, “Cousin Joseph,” will hit bookshelves in July 2016. It continues to explore the noir form in a detective story about the Hollywood blacklist—the titular Joseph—and how it shaped America for the future. Currently, he is completing the third, with the working title, “Ghost of Script.”

A few years ago, director/producer Dan Mirvish met Mr. Feiffer while working on the Richard Altman film, “Popeye”—which Mr. Feiffer wrote—and discovered his screenplay, “Bernard and Huey.” Now updated and set in 2010 with flashbacks to 1986 when it was written, the production will stage in spring 2016, Mr. Mirvish anticipates. Tracking down the script, which Mr. Feiffer had virtually forgotten about, was a feat in and of itself.

“These characters are deeply embedded in [Feiffer’s] oeuvre going back to 1956, the year he started the script in the Voice,” Mr. Mirvish said during a recent telephone interview.

Beyond their presence in numerous cartoons, Bernard and Huey appear in various guises and in various genres. In the movie, “Carnal Knowledge,” for instance, the Jack Nicholson character—a misogynist who always gets the girl into bed—is like Bernard in a certain sense. While the gentler Huey, who consistently falls short of fulfilling his sexual expectations, is often considered somewhat autobiographical, although this is not necessarily what Mr. Feiffer will confirm.

Regardless, in the film, their roles are reversed. When a disheveled Huey shows up on Bernard’s doorstep, a series of dalliances, misalliances and betrayals take place, capturing these now middle-aged men as they wrestle with relationships, sex, fatherhood, and friendship.

When it comes to transporting a cartoon character to the screen, Mr. Feiffer is far from a novice. The best example is the film, “Popeye,” which succeeds so beautifully in giving the characters the extra dimension that makes them feel to us as though they are real people.

“When I started writing it, I was flummoxed,” Mr. Feiffer admits, “until I came up with the idea that it’s not Popeye and Olive Oil, it’s Tracy and Hepburn in ‘Adams Rib.’ And, suddenly, they took on flesh.”

While seeking an afterlife for cartoon characters on Broadway has been something of a shot in the dark for some, it hasn’t eluded Mr. Feiffer. Working with composer/lyricist Andrew Lippa, who is known for “The Addams Family” and “You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown,” the two have adapted Mr. Feiffer’s first children’s book, “The Man in The Ceiling,” for a full-scale New York production, which is still in the works. About a boy who is a cartoonist, the book demonstrates Mr. Feiffer’s incisive take on character and relationships, while also featuring his signature drawing style and agile lines.

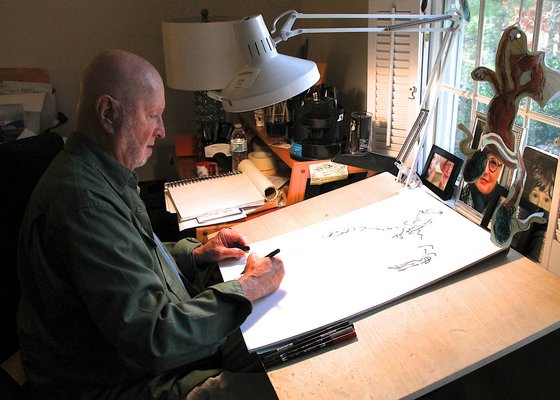

He continues to draw his dancers in the effortless style of Fred Astaire. He still draws every day, either when he gets up or before he goes to bed. During a recent visit, his drawing of an angular man dancing in his tuxedo lay glistening under the morning sun in the studio where he works.