January 28, 2011 was an ordinary day at the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center in Springs. The museum was closed for the winter, its director Helen Harrison free to go about her day-to-day errands.

This year is an entirely different story. After all, it’s not every January 28 that the legendary artist Jackson Pollock would have turned 100.

“It’s a good excuse for a party!” Ms. Harrison said at the museum last week. “But other than that, this is a guy who changed the course of international modernism, not just western art. This is an artist worthy of celebration.”

The powers that be at the Smithsonian American Art Museum agree. A centennial tribute to Pollock, “Memories Arrested In Space,” compiled from the museum archives will open on his 100th birthday in the Lawrence A. Fleischman Gallery in Washington, D.C. Ms. Harrison—a foremost authority on Pollock and his lady love, Lee Krasner—is the curator of the exhibit, which is chock-full with photographs, documents, magazine clippings and other ephemera that, together, take a peek inside the artist’s past.

“It’s just a very personal, very eclectic kind of thing you’d have in a shoebox under your bed that you just kept because it had meaning for you,” Ms. Harrison said of the collection.

This Saturday, here on the East End, Ms. Harrison will be hosting a birthday party for Pollock at the Springs Community Presbyterian Church and screening the Academy Award-winning film “Pollock,” starring Ed Harris and Marcia Gay Harden, which was partly filmed on location in Springs almost 13 years ago.

“A lot of bio-pics about artists are sort of love stories or about the drama of the creative life, but they’re not really about the art,” Ms. Harrison said. “The art is sort of secondary, and the fact that the people are artists just adds a little spice to the mix. In this case, it’s really about people—Jackson Pollock and his wife, Lee Krasner—who are living the creative life and making art. Ed Harris really nailed it.”

The first time Pollock and Krasner met was at an artists’ dance in 1936, Ms. Harrison said. His future wife was on the floor with another man when Pollock cut in.

“But he was a terrible dancer and he also had a bit of a skinful at that point,” Ms. Harrison said. “I mean, the guy was an alcoholic, let’s not mince our words here. He had been a heavy drinker since he was a teenager. And in 1936, he’s only 24 years old.”

According to Krasner’s own telling of the tale, Pollock stepped all over her feet and then had the audacity to proposition her, Ms. Harrison said. She blew him off, never expecting to see him again.

And she didn’t, until five years later. The pair was invited to participate in an exhibition of French and American painting by the likes of Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Willem de Kooning and Stuart Davis. The only name Krasner didn’t recognize was Pollock’s. Ironically, and rather conveniently, at the time he lived on 8th Street, just around the corner from her apartment on 9th.

“So, as she put it, she ‘hoofed over there’ and she goes up to his studio, knocks on the door,” Ms. Harrison said. “He’s hung over, opens the door and she says, ‘Hi, I’m Lee Krasner,’” Ms. Harrison imitated in a Brooklyn accent, “‘and I want to see your work.’”

He let her in. Her eyes darted around the studio from canvas to canvas, “dazzled” by what she saw, Ms. Harrison said.

By this time, Pollock had already experimented with unorthodox techniques involving enamel paint—including paint pouring and even flinging the liquid, which became his trademark more than a decade later. But in the early 1940s, Native American motifs and other pictographic imagery played a central role in his compositions, marking the beginning of a mature style.

Krasner had never seen anything like it.

“She had no idea that anybody was doing work that was so different from the direction that she and most of the other young avant-gardists were headed in,” Ms. Harrison said. “She fell in love with the work and, as an added bonus, she fell in love with the guy. The feeling was mutual. And yes, she absolutely recognized him and forgave him as soon as she saw the work.”

According to Ms. Harrison, Pollock was high maintenance, and Krasner recognized that from the beginning. But she thought his art was genius and that she could give him the emotional and moral support he needed, Ms. Harrison explained.

After they married, the couple spent a summer on the East End in 1945 and Krasner suggested to her husband that they invest in a winter rental—away from Pollock’s drinking buddies, away from temptations and away from distractions.

“Jackson says, ‘Are you nuts? Leave New York? Why would I do that?’” Ms. Harrison said. “He didn’t want to move to the country. He had grown up in the country, in Arizona and California. Very rural, had lived on farms, and that wasn’t his idea of an art life.”

When they returned to Manhattan after Labor Day that year, Pollock spent three days on the couch, mulling over the idea, Ms. Harrison reported. He came up with an even more radical proposal than his wife’s: buy a house in Springs and settle down.

In 1946, they did. It is now the Pollock-Krasner House and the site where Pollock created what is said to be his most innovative and influential work.

“Jackson said on more than one occasion that he didn’t move to the country,” Ms. Harrison said. “He moved away from the city.”

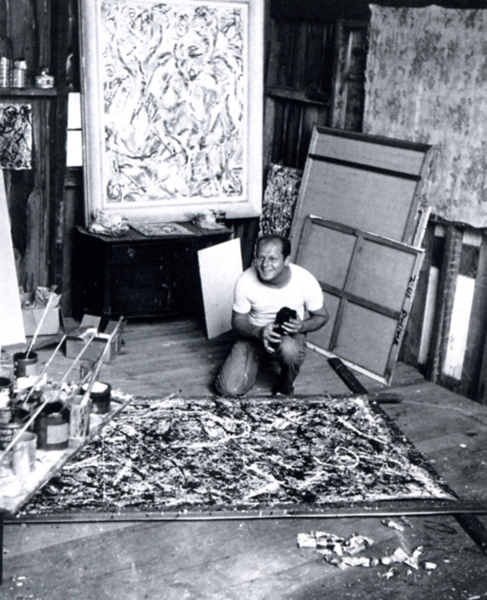

He gave up drinking for two years. In a small barn studio, he would spread his canvases on the floor and developed his compositions by working on them from all four sides. His artistic vision was freed from the influences in Manhattan. His colors brightened, his work opened up and his imagery reflected a new responsiveness to nature, according to Ms. Harrison. Soon, he pioneered the spontaneous pouring technique for which he is now internationally known.

“This is the myth about Pollock,” Ms. Harrison said. “You see these photographs of him with his furrowed brow and his kind of grumpy expression. But he lived a life like anybody else. He had fun. We have pictures of him smiling. People don’t see that side of him because they look past that to the tortured genius.”

Mr. Pollock made friends on the East End—some of them remember him as a “joker” and “a stand-up guy,” Ms. Harrison said—and was very productive during his sober years. Drinking did not release the creative energy, Ms. Harrison said. It shut him down. He was either drunk or working. That was the problem. And it was a problem that eventually caught up to him.

Pollock fell off the wagon again in 1951. He visited psychiatrists, dieticians and even attended Alcoholics Anonymous, which didn’t work because he wasn’t much of a talker, Ms. Harrison said. As he drank more, he worked less.

“He said to Lee one time, ‘The problem is not the work,’” Ms. Harrison said. “‘It’s what to do when you’re not working.’”

Pollock abandoned non-objective imagery for abstracted references to human and animal forms. He gave up color and created a series of stark black paintings. His art underwent a series of revisions, some of them more successful in adding back color and layers than others.

In 1955, Mr. Pollock’s alcoholism took over. He stopped painting altogether and drove his wife away. In the summer of 1956, she took a trip to Europe to re-evaluate their relationship, leaving Mr. Pollock behind with his mistress, Ruth Kligman. His new paramour was 26. He was 44.

“She hero-worshipped him,” Ms. Harrison said of Ms. Kligman. “It was very flattering. Here’s this young, beautiful woman telling him he’s the greatest thing since sliced bread. He bought it.”

The date was August 11, 1956. Mr. Pollock, Ms. Kligman and her friend from Manhattan, Edith Metzger, were on their way to a local concert when he decided to turn around and head home. He’d been drinking all day, Ms. Harrison said.

Speeding around a turn, he flipped the car, tossing all three riders. Mr. Pollock hit a tree and died instantly. The car rolled over Ms. Metzger and broke her neck. Ms. Kligman was the only survivor.

Krasner received a telephone call the next day with the news. She flew home from Paris.

“Lee was his sole heir and she became the keeper of the flame,” Ms. Harrison said. “She kept him in the public eye and his work in the right collections, the right exhibitions and the right books. She made sure people didn’t forget him.”

Krasner molded Pollock’s legacy, Ms. Harrison said. And on what would have been his 100th birthday, more than half a century after his death, he is still very much alive.

Marking the 100th anniversary of Jackson Pollock’s birth, the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center will host a birthday party in the artist’s honor at the Springs Community Presbyterian Church on Saturday, January 28, from 6 to 8 p.m. The movie “Pollock” will be screened, refreshments will be served and a conversation is planned. The event is free and open to all. For additional information, visit pkhouse.org.