The Montauk Bluffs were much easier to climb in 1949. Alex Matter would know.

As a young boy, Mr. Matter trekked up and down them alongside Jackson Pollock, who was oftentimes bogged down by camera equipment, working as a production assistant on the film, “Works of Calder,” by the late Herbert Matter—the then 7-year-old’s father.

At the time, Pollock was just another one of the Matter family’s unknown, starving artist friends scraping by on the East End. That is, until he wasn’t.

This year, Pollock—now known as the most legendary abstract expressionist in the world—would have turned 100, if not for a drunk-driving accident that killed him on August 11, 1956.

“My experiences with him were very good. I mean, he was terrific with me, with kids in general,” Mr. Matter recalled during a telephone interview last week. “Not the image he’s given, of being a loud drunk and crazy man. He wasn’t like that with me at all. He was very kind and soft.”

The 20-minute “Works of Calder” documentary— which fuses footage of another of Mr. Matter’s friends, artist Alexander Calder, producing mobiles in his Connecticut studio with motion-centered art related to the changing Montauk environment—will be screened later this month during “Artists Make Movies: Motion and Emotion” at the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center in Springs.

In honor of Pollock’s birthday, for the first time in the series’s 12-year history, the films—which celebrate early experimentation and will be shown every Friday night in September—all have a connection to the abstract expressionist.

“This whole year, everything’s been around him,” art critic and series curator Marion Weiss said during a telephone interview last week. “There’s a fascination here because, of course, he lived and worked here, and people are still here who say, ‘I remember him. I talked to him. I went to his house.’ That has nothing to do with the quality of his work, but it is a fascination. And the fact that he just threw traditions to the wind and said ‘I’m going to do what I’m going to do.’”

That much Pollock and the late photographer Val Telberg had in common, according to his son, Rick Telberg, a Sag Harbor native who now lives in East Hampton.

“My father was recognized from the beginning as an abstract expressionist, but they weren’t sure whether to call him an artist or a photographer,” Mr. Telberg said during a telephone interview last week. “At that time, those things were mutually exclusionary. He was the only photographer working as an abstract expressionist, and the only abstract expressionist working as a photographer.”

The senior Mr. Telberg, who died in 1995, liked the juxtaposition between dream and reality, the natural contraction between memory and experience, his son said. The result was photographs with a surreal quality, he said.

“It was something he could be a master of and nobody else was doing it,” Mr. Telberg said. “It was the very epitome of being an original.”

Recently, he went digging through his childhood attic and stumbled across cans upon cans of 16-millimeter film. After filtering out the footage from his old birthday parties, he struck gold: two homages to his mother, choreographer Lelia Katayen, which will be screened at the Pollock-Krasner House on Friday, September 14.

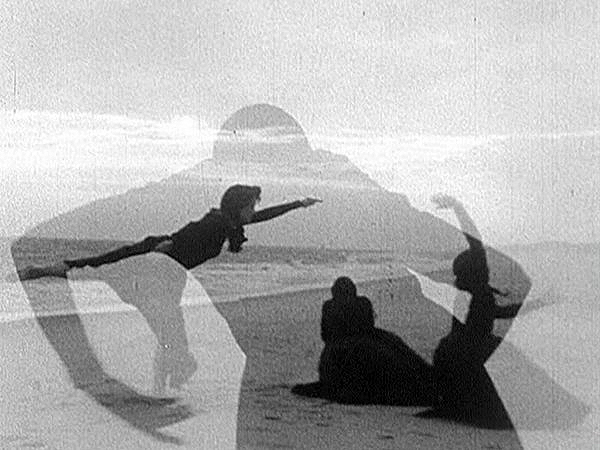

The 6½-minute “Montage Haitien” shows Ms. Katayen dancing with native Haitians. The second, nearly 6-minute film, “Widow’s Walk,” captures her cavorting on the beach in Amagansett.

The photographer filmed his wife by first shooting a scene on his 16-millimeter camera, rolling back the film, shooting over it and rolling it back again for another layer, creating improvisational, serendipitous moments, his son reported.

“It was, just, wow,” Mr. Telberg recalled of his discovery. “Look at what these people were doing 50, 60 years ago. Look at what they were doing with such crude equipment, such ancient equipment. Look what they were doing with such simple, but powerful ideas. It’s black and white. It’s grainy and we don’t have the sound to it anymore. But it’s powerfully evocative because of its directness. The images, the movement, the pacing are all very, very clear. The idea was, ‘We’re going to let the paint fall where it wants.’”

While the senior Telberg and Pollock weren’t necessarily friends, they ran in the same social circle, his son said.

All of the East End artists knew one another, whether they were photographers, painters or filmmakers, Ms. Weiss noted. They formed a community.

“They all went to the same parties,” Mr. Telberg said. “It was that time out here. That was when the Hamptons and Springs were a place where poor artists could find space and light. It didn’t cost much. The first house my parents bought was in a tax sale for $1,300.”

Pollock and his wife, artist Lee Krasner, moved to the East End in 1945 with a $2,000 down payment on their home, which allowed them a $3,000 mortgage from the local East Hampton bank. They made friends in the area, such as Mr. Matter and his son, who was the main character in his father’s film. It was shot through his eyes, Mr. Matter said, so he became close with Pollock during the summer months they spent filming on the Montauk cliffs, away from their home in Manhattan.

“Jackson had this crow that he would call out of the woods,” Mr. Matter recalled. “His name was ‘Caw Caw,’ and he would call it and it would land on his shoulder or arm. And he taught me how to do it, which was quite a thrill for a little kid, to have a crow come out of the woods and land on your arm.”

One summer, the Matter family rented right down the road from Pollock’s home in Springs, and it didn’t take long for the abstract expressionist to notice that the young boy was often alone.

“So he got me a pet goat. And I loved that goat,” Mr. Matter sighed. “I would sleep with it at night outside. I remember, once, I got a severe case of poison ivy because, unbeknownst to me, we were sleeping in poison ivy.

“When we went to the beach one day, my mother left him tied up to a tree,” he continued. “When we got back, he had choked himself to death, and I was absolutely heartbroken. Jackson made it a lot easier because he gave him a funeral and told me that we would be together again, later. And that made me feel a lot better. He was very, very cool.”

The only time Mr. Matter witnessed an inebriated Pollock was during a party at his parents’ house in Manhattan. The artist stumbled into Mr. Matter’s bedroom, in search of the bathroom, and decided to plop down on the boy’s bed instead.

“He tried to convince me to come down to the party. And I’m, like, 8 years old. And it was two in the morning,” Mr. Matter laughed. “Finally, he left and promptly fell down the stairs and broke his leg and an ambulance came and broke up the party. That was really the only time I saw him drunk, and he was actually quite funny. Not loud or mean. I have nothing but good memories of Jackson.”

The “Artists on Film” series will continue with Val Telberg’s “Widow’s Walk” and “Montage Haitien,” and Maya Deren’s “At Land” on Friday, September 14, at 7 p.m. at the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center in Springs. Admission is $5, or free for members. Additional screenings will include “Works of Calder” by Herbert Matter on Friday, September 21, and a number of short films by Len Lye on Friday, September 28. For more information, call 324-4929 or visit sb.cc.stonybrook.edu/pkhouse.