[caption id="attachment_64006" align="alignright" width="505"] Untitled 75, 2017, 31 x 13 x 19-1/2 inches. Bronze, Ed. 1 od 1, by Benjamin Keating[/caption]

Untitled 75, 2017, 31 x 13 x 19-1/2 inches. Bronze, Ed. 1 od 1, by Benjamin Keating[/caption]

By Michelle Trauring

Benjamin Keating held his grandmother’s hand as she started to cry.

“What’s gonna happen with all my stuff when I die, Ben?” she had asked him, terminally ill, at her home in Brooklyn, which had been in the family since 1898. “What’s gonna happen with the house?”

“Well, I’m gonna buy the house,” he recalled saying. “And I’m gonna take all the furniture and make it into sculpture, and make millions of dollars off of it.”

Her face lit up.

She would die three years later, and her grandson stayed true to his word. Once the house was his, he got to work. The project — casting the entire contents of her home, and parts of the home itself, in aluminum, an endeavor that the artist estimates will take him five years — is still incomplete, but that didn’t stop it from inspiring a number of the artist’s most recent works, debuting in his first-ever solo show, “On View,” on May 12 at Tripoli Gallery in Southampton.

“I have to give Trip the credit for pushing me into it,” Mr. Keating said of the exhibition. “I realized sometimes the universe does things for a reason. My first professional practice out of college was in the Hamptons, so it started to make a lot of sense. I said, ‘F--k it, let’s do it.’”

Mr. Keating is not one to pull punches. He tells it like it is, without hesitation, in a thick Brooklyn accent. It hints at his childhood, when that mentality kept him strong while growing up in a tough neighborhood in the 1980s. “I was the only white dude for miles, literally, growing up,” he said. “Mostly the neighborhood was rejecting them, but we weren’t racist. My family wasn’t that way.”

It was right around the time his parents divorced that Mr. Keating built a lean-to in the yard and bought his first torch.

He was only 10 years old.

“I had bullets and the torch and I was making these sculptures. I was a young kid. I was stripping them and I had these cigarette butts and I was melting them and making these fiberglass shapes,” he said. “My mother didn’t know what I was doing back there. When she saw, that was the end of my sculpture career for a minute.”

The artist would return to sculpture at age 18, sticking to his first love, poetry, in the interim. But after college, something changed within him, and he found himself living and working at Nova’s Ark in Bridgehampton from 1998 to 2000.

There, he earned $100 per week, plus room and board—“I was the poorest kid in the Hamptons,” he said—but it was relatively enough. It was his start.

[caption id="attachment_64015" align="alignright" width="551"] POH18, 2017, 50x42x6 inches, aluminum, Ed. 1 of 1, by Benjamin Keating, on view at Tripoli Gallery in Southampton.[/caption]

POH18, 2017, 50x42x6 inches, aluminum, Ed. 1 of 1, by Benjamin Keating, on view at Tripoli Gallery in Southampton.[/caption]

It was on the East End where the sculptor came into his own. And it was meeting artists from all walks of life that gave him confidence and a voice, and laid the course.

“I didn’t want to be a plumber, I didn’t want to be a doctor, I didn’t want to be a lawyer, I didn’t want to be rock star, I didn’t want to be an astronaut. I just wanted to be a poet and an artist, and I figured that would be the thing that would get me out of my lower-middle class kind of mentality. I figured that was the thing to get me out,” he said. “Mainly, what I learned in Bridgehampton was that I could do it. If all these other f--kers could do it, I could do it. I was like, ‘Holy s--t, I might be able to pull this off.’ It really showed me I could do it.”

His artistic process begins with a pattern that can be burned, whether it’s wax, wood, or another organic material. It’s invested in ceramic, burned out and replaced by molten metal. Sometimes, he then carves into the metal sculpture before polishing it, he said.

“I used to work with found objects, and abstract objects, and then destroy them. It was always the way I made art—building, destroying, building, destroying,” he said. “But, say, with my grandmother’s couch, I didn’t treat it like a piece of furniture or a kid’s toy that I destroyed when I was 19 and made art out of. That’s where a new thing happened with me. It was in between carving and destruction that became more this gestural approach to working with canvases and making the object and then destroying the object.”

He laughed. “It doesn’t make much sense, does it?”

The five sculptures, nine paintings and 10 works on paper all began as just that, he explained, but they are now all cast in metal. Each piece, completed in 2017, found inspiration within the past, present and future of abstract art, and his grandmother’s house project, a series he will eventually title, “A Piece of Her That’s Missing.”

It is his most recent work that has made Mr. Keating love art now more than ever, he said.

“I’m finally starting to get somewhere with it. My studio’s better than it ever was,” he said. “I’ve always been on a progression. I’m not a rocketship, I’m like a big heavy tank moving up a hill. And it’s solid, so it feels better. I have ground beneath me, not a bunch of rocket fuel in the air. When that rocket fuel burns out, you might just be falling back to the ground, you know? We’re just trying to climb up the hill.”

“On View,” featuring work by Benjamin Keating, will open on May 12 at Tripoli Gallery in Southampton. A reception will be held on May 13 from 6 to 8 p.m. The exhibition will remain on view through June 11. For more information, call (631) 377-3715, or visit tripoligallery.com.

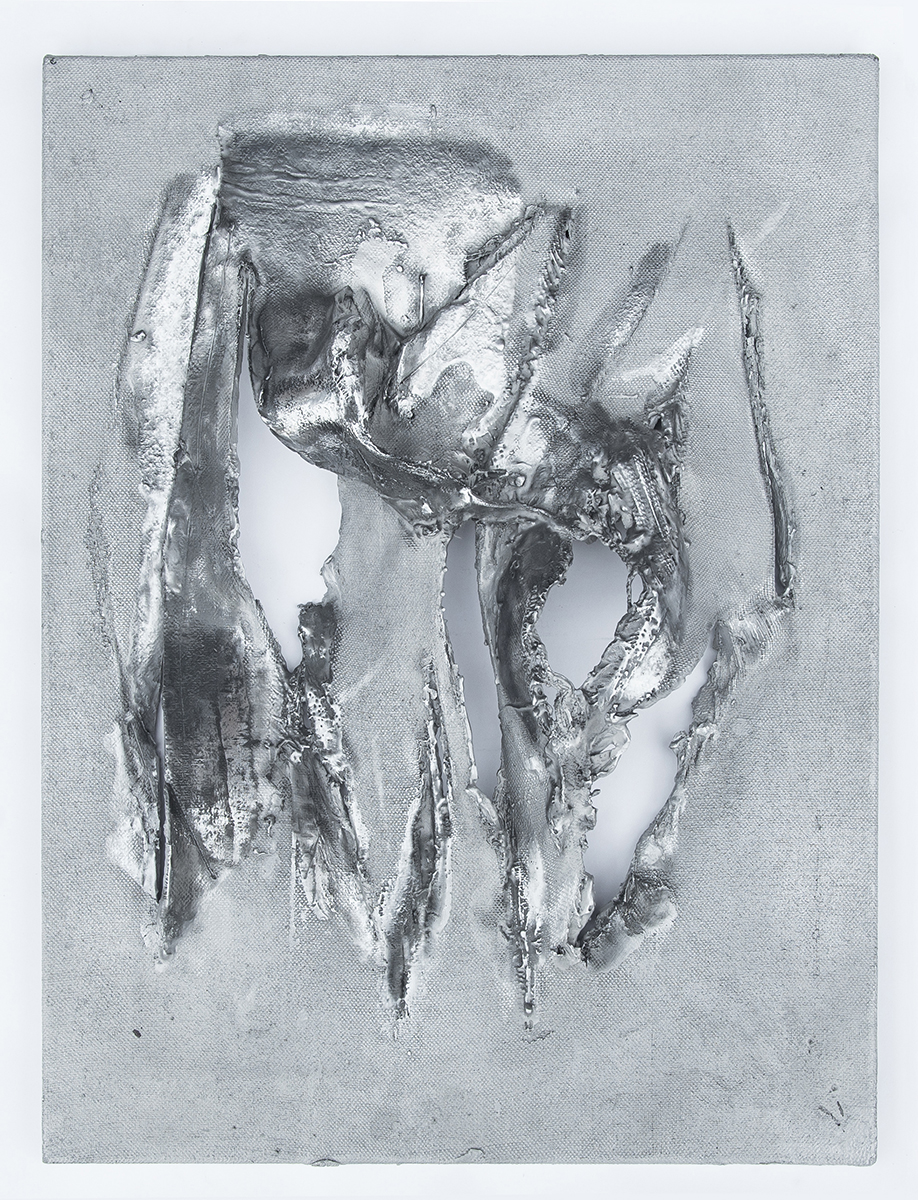

[caption id="attachment_64018" align="alignnone" width="783"] POH15, 2017, 24x18x6 inches, aluminum, Ed. 1 of 1, by Benjamin Keating.[/caption]

POH15, 2017, 24x18x6 inches, aluminum, Ed. 1 of 1, by Benjamin Keating.[/caption]