“Black art has always existed. It just hasn’t been looked for in the right places.”– Romare Bearden

For years, Dean Mitchell refused to show his face — not to accept the awards he won in fine art shows, not when the magazines came knocking, and certainly not to promote himself.

Because in order to keep gaining momentum, no one could know he was African American.

“I did not want race to interfere with my progress here, because all I heard was I wasn’t gonna make it because I was black,” Mitchell recalled during a recent telephone interview. “I couldn’t get into any galleries because they were scared they’d run off their clientele, and I couldn’t hardly sell my artwork, but I could win about $30,000 in prize money, as long as they didn’t know who I really was.”

In 1987, that finally changed when American Artist magazine ran an article on Mitchell, with a photograph, that would lead to his first museum show, fan his now four-decade-long career, and land him in a seat across from President Barack Obama in the White House, interviewing as one of four contenders to create his official National Gallery portrait.

[caption id="attachment_100097" align="alignnone" width="508"] "Buffalo Soldier in Blue" by Dean Mitchell.[/caption]

"Buffalo Soldier in Blue" by Dean Mitchell.[/caption]

“I told him, ‘Even if I don’t get to do your portrait, I have already won,’” Mitchell said. “‘The fact that I am sitting in the Oval Office talking to you about doing your portrait, I started with a Paint-By-Numbers kit from the South. This is a fricking miracle that I’m sitting here.’”

The 2018 Obama portrait appointment went to Kehinde Wiley, but for Mitchell, to be considered was ultimately enough — a source of validation that he never expected, from a man who helped pave the way for mainstream African American curators who have championed black artists ever since.

But there is still a long way to go, the art world agrees, and RJD Gallery in Bridgehampton is doing its part to right those wrongs with its annual Black History Month exhibition, opening Saturday with work by Mitchell, Phillip Thomas, Stefanie Jackson and Jules Arthur.

“From our first show celebrating Black History Month, we knew we wanted to make it an annual show,” said gallery director Joi Jackson Perle. “It’s important that everyone’s art is celebrated and, quite frankly, artworks by black artists have been sadly underrepresented in galleries and in print. The world is a wonderfully diverse place and we want to celebrate that diversity through art, and we are proud to highlight that diversity through this annual exhibition.”

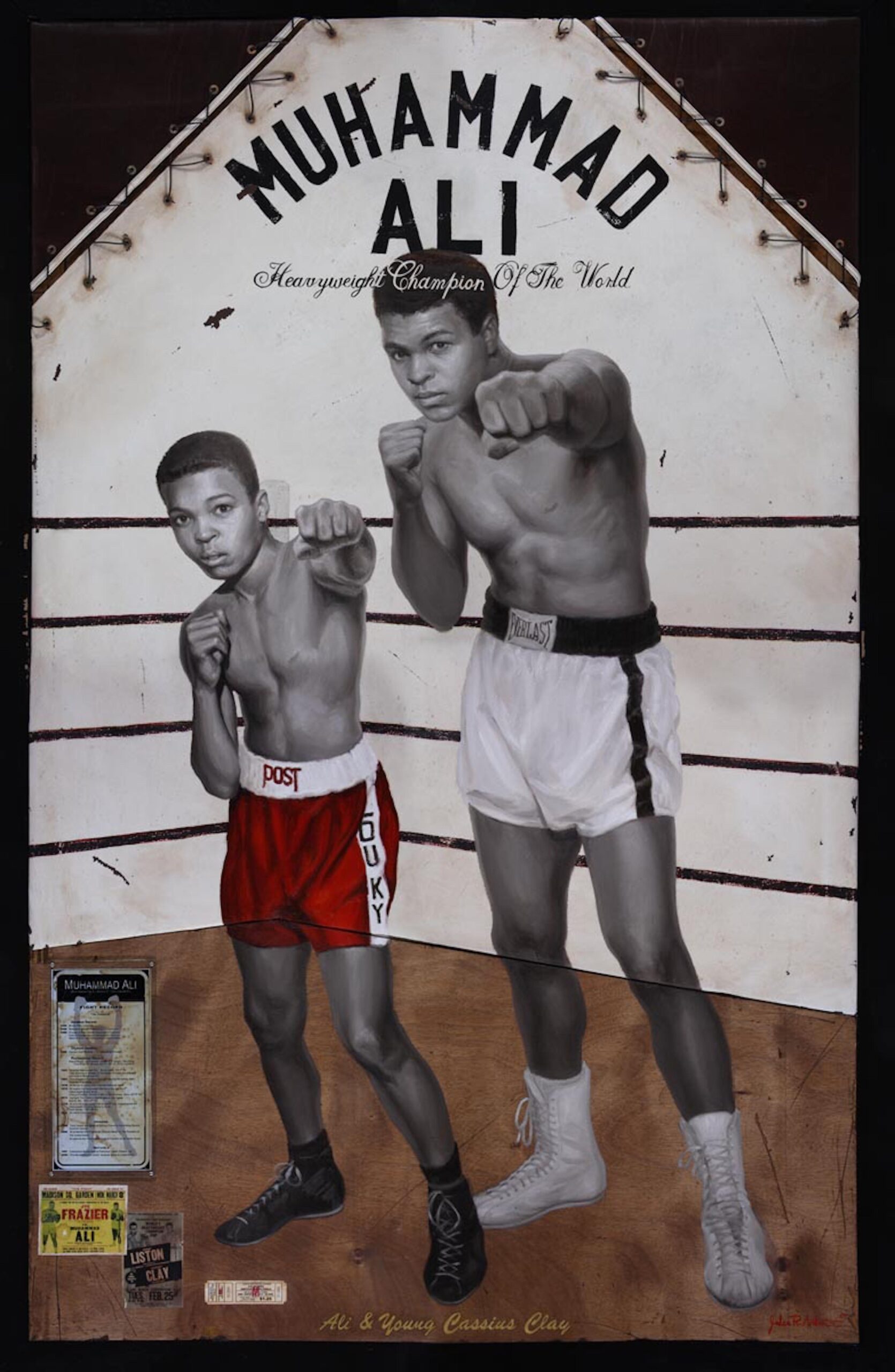

[caption id="attachment_100098" align="alignnone" width="392"] "Ali and Young Cassius Clay" by Jules Arthur.[/caption]

"Ali and Young Cassius Clay" by Jules Arthur.[/caption]

The theme, “A Time and A Place: Layers of Black History,” can be seen in the artists’ examination of their own histories and experiences in the world — in Mitchell’s rural landscapes and Buffalo soldiers, in Thomas’s narratives from Jamaica, in Jackson’s surrealist scenes, and Arthur’s immersive canvases, from Mohammad Ali’s boxing gym to the birth of jazz in New Orleans.

“I hope that my work has the same ability to come into people’s vision and mind, and educate, entertain, fulfill,” Arthur said. “It would be nice when it’s all said and done that Jules Arthur created an impactful work that spoke of the black experience, celebrated its accolades, its achievements. That would be my hopes and dreams, being a 21st-century artist creating work in this special time.”

The present-day rise of black art in America is not lost on Mitchell, who grew up poor in Quincy, Florida, where racism was very much alive in the 1960s. And although most of the small industrial town did not support him — “I had a junior high school art teacher that took me around here, trying to help me, and he got called ‘the n----r lover,’” Mitchell said — his grandmother stepped up to give him the love and encouragement he needed.

“My grandmother was a very bright woman, but she only had a fourth-grade education. She just didn’t have the opportunity,” he said. “Sometimes I do feel like there is a certain kind of classism even among people of color, and that has always disturbed me because everybody has to start somewhere and nobody picks the space and time in which they’re born. It just so happens she was born during a time when there was a lot of oppression, so she did not have the opportunity.

[caption id="attachment_100099" align="alignnone" width="600"] "Love's in Need of Love Today" by Stefani Jackson.[/caption]

"Love's in Need of Love Today" by Stefani Jackson.[/caption]

“I’ve had the opportunity based on the fact that my grandmother pushed me,” he continued. “So I’ve crossed into an arena that I thought would never happen.”

Over his prolific career, Mitchell has won more than 600 awards, including the T.H. Saunders International Artists in Watercolor Competition and the American Watercolor Society’s Gold and Silver Medals. His notable watercolors of African American soldiers in the American Revolution and Civil War live in private collections and museums worldwide — shining a light on a rarely acknowledged part of history.

“The black image in American culture has been somewhat vilified. And if it hasn’t been vilified, it’s been dismantled through buffoonery,” Mitchell said. “What I’ve tried to do, in some way, is to not make us feel like we’re a threat. I’ve tried to present ordinary people in American culture with a certain amount of dignity and just a human quality to them — just for people to look at them as full human beings who have a passion for a better way of life. I don’t feel like I need to exaggerate who we are to make us fully human.”

The men and women Mitchell paints are “hardworking, average Americans,” and he approaches them with a deepness and spirituality that dispels the narrative of disrespect that he, too, has experienced.

“By America’s idea of the black male growing up without a father in his life, and with all these obstacles, I should not … I have defied a lot of those odds,” he said. “I’m not putting myself on a pedestal because the bottom line is, I’ve had a lot of strong black women pushing me, too. And that has made all the difference in the world. I celebrate that ordinary person. I celebrate that. I do not run from it. There is no shame in being poor, there is no shame in that for me. I celebrate it.”

[caption id="attachment_100100" align="alignnone" width="600"] "What's On Your Mind" by Phillip Thomas.[/caption]

"What's On Your Mind" by Phillip Thomas.[/caption]

And, in time, Mitchell has also come to accept, and celebrate, exactly who he is.

“I just want people to understand, when they walk in the door to look at my work, this has been a long journey,” he said. “This has been a long journey.”

RJD Gallery, 2385 Main Street, Bridgehampton, will open “A Time and A Place: Layers of Black History,” featuring work by Jules Arthur, Stefanie Jackson, Dean Mitchell and Phillip Thomas, with a reception on Saturday, February 22, from 6 to 8 p.m. The show will remain on view through March 16. For more information, call 631-725-1161 or visit rjdgallery.com.