[caption id="attachment_49089" align="alignnone" width="800"] 1690 Christopher Browne Map of Long Island and North Sea.[/caption]

1690 Christopher Browne Map of Long Island and North Sea.[/caption]

By Michelle Trauring

[caption id="attachment_49087" align="alignleft" width="300"] 1767 Illustration of the Townshend Acts[/caption]

1767 Illustration of the Townshend Acts[/caption]

The single most important event to happen in Southampton, save for the 1640 landing by English pioneers, cannot be found in most history books.

It was 1776. Newspapers were virtually non-existent. Written records were few and far between. As for those keeping them, no one wanted to remember the atrocities unfolding not only in Southampton, but Long Island-wide, at the hands of the British soldiers, who occupied the East End and beyond during the Revolutionary War.

“I’m from Maine and, when I bring this up—‘You know, Long Island was occupied by the British’—nobody knows that,” said Emma Ballou, who has curated the first-ever exhibition on the subject, “Southampton Under Siege,” opening Saturday, March 19, at the Southampton Historical Museum. “It’s past time we do this.”

[caption id="attachment_49088" align="alignright" width="300"] 1874 Painting by Alonzo Chappel of The Battle of Long Island[/caption]

1874 Painting by Alonzo Chappel of The Battle of Long Island[/caption]

The exhibition is a year and a half in the making, according to Ms. Ballou. She worked closely with museum volunteer Megan Flynn and Research Center Manager Mary Cummings, who waded through the extensive library and archives to get down to the truth of what exactly unfolded during the last seven years of the Revolutionary War.

“Accounts of the suffering and humiliation endured by the families who were unable to leave Southampton when the British arrived brought home to me just how terrible it is to live under occupation, as the French did during World War II and so many others are experiencing even now,” Ms. Cummings said in an email.

The back-story to the eventual occupation is important, Ms. Ballou explained during a recent telephone interview. In 1740, the village’s Massachusetts emigrants were living happily in Southampton, celebrating a century of relative bliss, much in thanks to their commercial ties to New England and Great Britain.

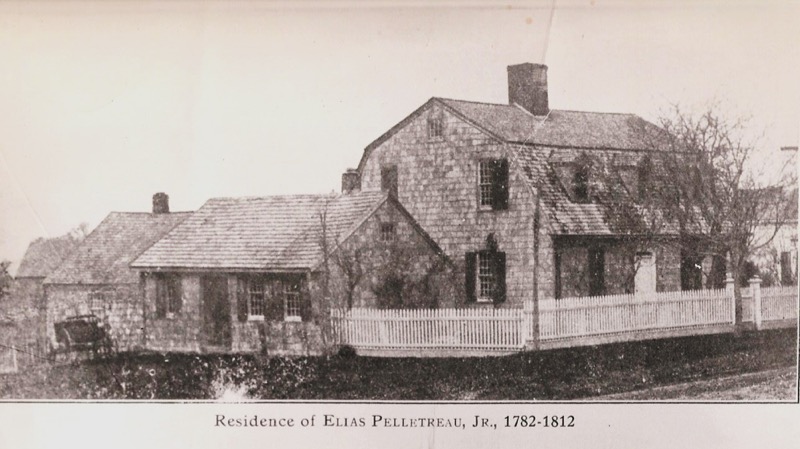

[caption id="attachment_49090" align="alignleft" width="300"] Residence of Elias Pelletreau 1782-1812, from the Collection of the Southampton Historical Museum.[/caption]

Residence of Elias Pelletreau 1782-1812, from the Collection of the Southampton Historical Museum.[/caption]

Three years later would mark the Boston Tea Party—when a group of Bostonians boarded British East India Company ships and dumped more than 300 chests of tea into the harbor, in protest of the 1773 Tea Act. Parliament responded by passing the Coercive Acts—dubbed the “Intolerable Acts” by colonists—in 1774, which closed the port, suspended the Massachusetts colonial charter, and implemented a military government.

The Coercive Acts distinguished Bostonians as martyrs for liberty, and the colonists flocked to the cause by sending goods and money, including in Southampton. In 1775, the war finally erupted, and the New York Provincial Congress passed an act declaring that any man who refused to sign the Articles of Association, which showed support for the Patriot cause, would have his weapons confiscated for the use of New York militia units.

“The paper went around asking all the Patriots to sign, and only two people in Southampton didn’t sign the paper,” Ms. Ballou said. “And at the end of the day, those people were convinced.”

[caption id="attachment_49086" align="alignright" width="237"] Portrait of General Meeigs[/caption]

Portrait of General Meeigs[/caption]

In July 1776, silversmith Elias Pelletreau pulled together his own militia, which consisted predominantly of grandfathers—making it, quite possibly, the only “grandfather militia” in the nation, Ms. Ballou noted. He warned the group to be ready for an imminent invasion.

He would turn out to be correct.

A month later, General George Washington retreated at the Battle of Long Island, givng the British strategic control of New York City and Long Island, effectively cutting off the Patriots from other Revolutionary sympathizers.

One out of every six people on Long Island fled, flocking to ships leaving out of Sag Harbor and other ports on the North Shore destined for Connecticut. The evacuees were mostly men—the strong, well-to-do heads of household.

“People left behind women, children, elderly, the sick and slaves,” Ms. Ballou said. “Affluent men left and, basically, it was the people that couldn’t afford to go who stayed behind and dealt with these British oppressors coming in, forcing them to sign an ‘Oath of Allegiance.’”

[caption id="attachment_49085" align="alignleft" width="300"] Portrait of John Hancock – 1770[/caption]

Portrait of John Hancock – 1770[/caption]

The occupation stretched across Southampton Town and into East Hampton Town, and a British officer was put in charge of every major village and hamlet. In Southampton, General Sir William Erskine was considered a “rather fair overseer of the town,” Ms. Ballou said—at least compared to Major Cochrane next door in Bridgehampton. He was brutal and notorious for his cruelty, which ranged from tormenting children to physically abusing his own soldiers.

“Only triumphant stories came down orally in Southampton, a very small farm village,” Southampton Historical Museum Executive Director Tom Edmonds said in a recent email. “There were no newspapers and the educated who could write were mostly in Connecticut. Town records from this period exist but the war is not mentioned. As you can imagine, who would want to be recorded documenting any horrors for fear of being branded a traitor and hung.”

For seven years, women and slaves feared violence and sexual assault on a daily basis. Resources were scarce. Farms were destroyed, crops were seized and houses were vandalized. Some homes in Bridgehampton still have the graffiti British officers carved into the walls, Ms. Ballou said. When British General Charles Corwallis surrendered at Yorktown in 1781, refugees returned from Connecticut to find Southampton in ruins.

“It was a very scary tense time on the East End,” Ms. Ballou said. “There were very few places where the British actually occupied an area. They didn’t have the manpower; they focused on raiding and battles. But because Long Island was so isolated, they were able to do that. A lot of people are surprised by this.”

Inside the Rogers Mansion, a timeline will border the exhibition room, which Ms. Ballou has repainted grey, giving the space a dark, heavy mood. The top of the timeline will explain national events, while the bottom will juxtapose what was happening on a local level.

“Being able to flip back and forth, it becomes more personal,” the curator said. “You can feel the stories of what was happening to the people here more.”

In the center of the space, an exhibit period room will show what a typical kitchen would have looked like for a local Southampton resident who stayed behind, Ms. Ballou said, which is nothing short of depressing. In contrast, a brightly lit corner of the room will recreate the dining room table of General Erskine, who took up residence in Elias Pelletreau’s home—one of the best in the village.

“They didn’t set up camp. They lived in the homes of the people that fled from Long Island,” Ms. Ballou explained. “Or, they took up part of the home of people who were living there. Sometimes, women and slaves and children had to give over half their homes to the British soldiers and generals who stayed.”

This specific period of history has recently snared newfound attention, due to the AMC series “Turn: Washington’s Spies,” which follows the story of a Setauket-based spy network during the Revolutionary War. Ms. Ballou said she decided to take advantage of the heightened interest for this exhibit.

It was funded by a grant from the Bath and Tennis Club Charitable Fund, as well as the Southampton Colony Chapter of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution—which is, coincidently, closely linked to the exhibit in another fashion.

“The Southampton Colony Chapter, their right to be in the DAR has been brought into question over this ‘Oath of Allegiance,’” Ms. Ballou said. “Their great-great-grandfathers signed that oath and the paper was sent to the national DAR in Washington, D.C. They said, ‘No, you can stay in the DAR, but your grandchildren can’t get in.’

“There’s a lot of various people in this community that want to bring awareness—that these people were coerced into signing this oath,” she continued. “And it should be viewed not as they were loyal to the British, but that they were basically prisoners of war.”

“Southampton Under Siege” will open with a reception on Saturday, March 19, from 4 to 6 p.m. at the Rogers Mansion in Southampton. Admission is free. The exhibition will remain on view through the end of the year. Regular hours are Wednesdays through Saturdays from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Admission is $4, or free for members and children age 17 and under. For more information, call (631) 283-2494, or visit southamptonhistoricalmuseum.org.

Regular hours are Wednesdays - Saturdays 11am-4pm ($4 non-members, members free and children 17 and under)