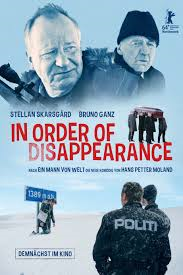

[caption id="attachment_54937" align="alignnone" width="1024"] Stellan Skarsgård in "In Order of Disappearance."[/caption]

Stellan Skarsgård in "In Order of Disappearance."[/caption]

In Order of Disappearance fits my category Movies That Should Play in Sag Harbor. It just opened Friday at the Sunshine Cinema in Manhattan and I’m surprised Norwegian director Hans Petter Moland’s wacky black comedy, is playing at all considering that I first saw it at the 2014 Tribeca Film Festival.

The premise for this Norwegian-Swedish-Danish coproduction: Nils (Stellan Skarsgård) is a snowplough driver, a model citizen in his Norwegian town. But when he discovers his son was murdered, he decides to exact revenge on the drug gang responsible, strategically eliminating one member at a time until he finds the arrogant, sadistic boss. As his marriage crumbles, he meets and grows fond of the boss’s young son, and finds them both caught in the crossfire between two rival gangs: one local, and one "imported" from Serbia and run by the ruthless Papa (Bruno Ganz). We meet a lot of fun characters along the way, including the many who soon “disappear.” In 2014, Moland and I spoke about his unusual revenge film.

Danny Peary: Was In Order of Disappearance the original title of Kim Fupz Aakeson’s script or did it become the title later on?

[caption id="attachment_54935" align="alignright" width="300"] Hans Petter Moland.[/caption]

Hans Petter Moland.[/caption]

Hans Petter Moland: The screenwriter is Danish so the original title was in Danish. The English translation was Prize Idiot. In Order of Disappearance is the title that I came up with. This story originated with me and we developed it together. It’s a story that I started working on many years ago, after my previous film [A Somewhat Gentle Man, also with Skellan Skarsgȧrd) played in Berlin. We collaborated on that, too.

DP: I guess your title indicates that you always wanted the film to have a humorous tone.

HPM: Oh, yeah.

DP: It wasn’t until he puts the rifle in his mouth while his son’s friend is lying there is when I realized there’s tongue-in-cheek humor in this movie. Is that the point at which you’re supposed to realize it?

HPM: That’s when people tend to realize it. It’s a moment that is tragic but at the same it becomes absurd and funny. It also has a plot revelation, which sends the whole story in a different direction. All of that has to work at the same time. Obviously, sometimes the audience will feel unsettled. I think the earlier scene when the body is identified at the morgue is the first indication of laughter. This gurney is pumped endlessly to raise the child, and it’s painfully humorous but it’s inappropriate so nobody laughs. Occasionally I can hear that somebody snickers. It never seems to end.

DP: This film could have been made entirely seriously.

HPM: Yeah, I mean it is serious, it’s just not told in a very deep and dark voice.

DP: Why at this point in your career did you want to make a revenge movie?

HPM: I’ve toyed with this story for quite a while. I’m quite interested in that sort of porous area where our civility is challenged and what is it that makes us either snap or lose faith or become like our enemies. We tend to tuck it away and hide it and it pops up and reminds us how wild and horrible human beings are capable of being. We’re also capable of great deeds.

DP: So you thought of this for a long time.

HPM: Yeah and as things come to fruition. At different times in your life, sometimes it’s right, sometimes it’s wrong. Because I started this relationship with this screenwriter – we had a lot of fun together. It’s a very serious subject but it’s probably better dealt with with some lightness.

DP: What his near suicide does, obviously, is show he doesn’t care if he’s dead and that makes him formidable. Is that your intention?

HPM: Yeah. It also says that he can’t live with the death of his son. He and his wife are devastated by the loss of their son but they just deal with it in completely different ways.

DP: Explain why he goes one way and she the other? It’s usually the mother who wouldn’t believe the son was an addict. This time it’s the father saying, my son wasn’t an addict.

HPM: My idea is this is a relationship, as you see in the beginning, they know each other very well, she even helps him to dress. It’s seamless. So there’s this routine, well-established, and they like each other. The tragedy that they encounter shows that their relationship isn’t capable of handling that. The family hasn’t been subjected to that much pressure before. It also shows it’s not a relationship that is founded on a deep understanding of each other. So when they’re at the morgue, his instinct is to say that he couldn’t be an addict, and hers it to say we have to reconcile ourselves with the realities of life. In essence she blames herself because right under our noses he became an addict and we didn’t see it. So she’s blaming themselves and the way they conducted their lives, and that reflects what she thinks about their relationship. Already they take different paths.

DP: I’m interested in that guilt. Does she blame him for raising their son so that he’d end up a dead addict?

HPM: I think she’s blaming them both, for not being more of a tight unit. She says that it happened without it registering on our radar.

DP: If he agreed with her when she said their son was an addict, would that have made any difference?

HPM: If they as a couple had decided to try to deal with it together, even the revenge might have been a joint project. She might have made him sandwiches before he went to town and conducted his business.

DP: Do you think at the beginning she knows what he’s doing when he disappears at nigh? Does she know he’s capable of doing what he’s doing?

HPM: She’s awake the first time he leaves. She knows he’s up to no good. But she doesn’t investigate.

DP: But he could go to a bar all night and drink away his sorrows.

HPM: I think within the framework of this film, she knows he’s up to something sinister.

DP: Is there any way to save them, do you think?

HPM: As a couple? I think she sums it up pretty well in her farewell letter. There’s nothing to say.

DP: Is he completely empty inside, at this point, is he going to be empty the whole way through? The little kid has some effect on him, but otherwise…

HPM: He doesn’t care, he doesn’t care about himself, so if somebody shoots him that’s fine.

DP: Do you think he’s the same at the end of the film, he still doesn’t care? Because he’s trying to save him, he goes under the car and stuff?

HPM: I think that’s some of the nature of revenge – you want to inflict pain, you want the pain that you are carrying to be transported onto someone else. You can’t bear to carry it yourself. Once the Count (?) is dead, and he has to face the future. The whole world we have encountered, for lack of a better term, is ethnically cleansed.

DP: I think of it as nihilistic.

HPM: Everything is wiped out. What remains is a child who is much smarter than his father, he has better instincts. He’s the hope. And Miller and a gay guy and two old men, that it.

DP: We were talking about how formidable he is, because he doesn’t care if he dies, but the scenes with the little kid show that he has some humanity left. That’s intentional on your part.

HPM: I think that child is purity and brightness and is capable of transcending his feelings. That just happens to be my son.

DP: A good kid!

HPM: I wanted to warn you in case you said something negative.

DP: No, I liked his performance.

HPM: I think he did really well.

DP: In theory, at the end of the movie he could put the rifle in his mouth again. He could think that he got the revenge he wanted but that he has no wife and no family and nothing left. But you don’t have him do that and I think it’s because he has regained his humanity.

HPM: The child does touch him. He managed to get under his skin.

DP: When the boy tells him about Stockholm Syndrome, explaining their bonding, people laugh.

HPM: I think that gets the biggest laugh in the film.

DP: In the Director’s Notes, you’re very serious on the subject. You say,” “I wanted to make a revenge story for a long time…If you can’t have justice, you may as well have some fun.” So it’s something you’ve thought about since you were young, and you have a kid, and the kid talks about bullies.

HPM: I don’t know if revenge is for everyone but retaliation is quite common. Fighting is common. I had a bully in my class, I fought him every week for seven years. There were other people who didn’t stand up to him.

DP: Did you father say, you have to fight him?

HPM: My father had spent five years in the war, so he was done fighting. It’s the mechanisms of what it does to your psyche. Your temperament drives you to want to smother somebody. I think life teaches you that there are better strategies for getting even. I think it happens all the time. You hear grown people with good schooling, occasionally, when they’re confronted with vile human beings they want some kind of retribution.

DP: Did you talk to your son about the themes of this movie?

HPM: Yeah, yeah. He went with all his siblings with me to the premiere. We talked about it en route, while making it, and he’s not a professional actor, so what we most talked about, of course, was number one, he didn’t want the job just by being my son. So the casting decision wasn’t mine alone, it was the casting director and producers who convinced me he was the best for the role. But also to let him not drowned in the theme of the film. I told him basically that he had a father who was hellbent on getting his way even when he’s wrong, and that he should pay attention in a way that he would pay attention to me, and look for discrepancies in my logic. I think in a way that’s what’s great about this age. Originally, in the script, he was younger. The fact that he’s intellectually capable of looking at his father and starting to form an opinion about his conduct. He’s a budding teenager. That’s one of the things I’m really proud of that he did. He can look and listen during the scene and then respond to what he has heard as if he’s heard it the first time, and reflect on it.

DP: Looking at all your other movies, age seems to be really important to you. You have young men and old men, kids and older people.

HPM: Families often are composed of different generations.

DP: In this film, the younger gangsters are closer to the old-style gangsters, they’re both stupid and they’re both evil.

HPM: I don’t know if I thought of it as dealing with age, but it’s interesting to explore life in all of the facets of it. If the character he had been forty years old this movie would have been completely different. It does something, some doors are shut. There’s no chance of starting over and getting a new child. That does something to the story.

DP: Talk about him and his brother. He became a citizen of the year, his brother was a criminal, but they both have the same potential for violence. I’ve always been interested in that in movies – two starting out the same way. Was that on your mind?

HPM: Well, it’s a story in the Bible.

DP: Cain and Abel, yeah.

HPM: Yeah, that’s interesting. Especially now that genes have been coming to the forefront of our discussions about who we are. It’s interesting to explore.

DP: In gangster movies, one friend can become a priest and one becomes a gangster, but they both have the same potential for violence.

HPM: It has to do with age, context, and what you’re subjected to. You may have been subjected to violence but you decide to become a priest because a priest has touched you. That is a way to deal with violence. But another kid might meet violence with violence, having seen somebody successfully retaliating.

DP: You’re a movie fan, so were you influenced by Lock, Stock, & Two Smoking Barrels, Smoking Aces, Snatch, Big Bad Wolves, The Big Combo, any of these?

HPM: I’ve seen Lock, Stock, & Two Smoking Barrels. I don’t live in a vacuum. I more attempted to make a film that really was irreverent to the genre.

DP: I think your film is beautiful, and the outside stuff is just gorgeous, unbelievably beautiful. There is a white motif. Did you say, I’m going to have everything be white?

HPM: It needed to be an expanse that is a wilderness that also has a barrnen, non-descriptness to it. Hi his job almost is futile, keeping this strip of road open. In a way, it’s symbolic – it’s what we do with out lives, we try to keep our little patch of civility, and our little landscape is not known to anybody else.

DP: It’s not film noirish, everything dark, it’s everything bright – which is unusual. Visually, as you wrote the script, you’re happy with the visuals?

HPM: I really like them, it was a deliberate choice.

DP: The plow thing?

HPM: To him, the work important. Not only does he think he has a sense of purpose, but he’s being honored for doing this job. He feels that he’s being recognized for what he feels is important. It’s what to him is every-day life, it has a meaningfulness and a beauty to it.

DP: Talk about the women in your film.

HPM: They’re smarter than the men. I think they disappear for very good reasons.

DP: Is this a world run by men?

HPM: The women see through them and they’re a part of what the men are up to. Even the ex-wife of the Count regrets having been mixed up in this, so she has a lot of strategies for getting out from under. So all the women in this film are in relationships out of need or a mistake, and they try to distance themselves.

DP: They all stay strong until the end. And Stellan Skarsgård, it’s your fourth film with him.

HPM: We’re good friends and like working together. I give him the script when it was finished? I think we make each other courageous.

DP: You’ve also gotten older together. Is there a wisdom that comes with this?

HPM: Well, I think there’s a value to the fact – in a way, because we have had success before, that can frighten and also stifle you – but it also gives you a reminder that it has come at a risk. You can’t eliminate risk, so you may as well just embrace it, and take risks that are worthwhile. I think we’re good at taking risks together.

DP: What does Bruno Ganz mean to you?

HPM: He’s only one of the greatest actors alive, so it’s been a dream since The American Friend to work with him. He and Stellan are two of the greatest actors, so getting them in the same movie was fantastic.