In September of 1908, nearly 40 years after slavery had been abolished in this country and black men were granted the right to vote, it would be another 10 years before women were allowed the same right.

Things were much different then than they are today. Civil rights had yet to see the giant leaps that would occur later in the 1900s and into the 2000s.

The color of a person’s skin played a large role in our justice system in the early 1900s. Crime reporting at that time reflected the attitudes of the day, and frequently specified the ethnicity of the people involved. Now, unless it is part of a description used to inform or enlist the help of the public, the race or ethnicity of the victim or the perpetrator is not a major part of the story.

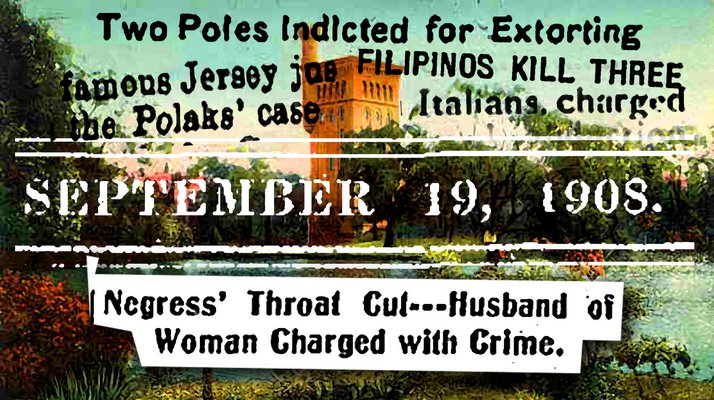

Looking at newspapers from September 19, 1908, headlines screamed such statements as “Two Poles Indicted for Extortion” and “Filipinos Kill Three.” Another story on that day told of an “Italian Detective” who was on a mission to apprehend “Polish Blackmailers.”

On that same day in September 1908 was the announcement that a “Riverhead Negro” had been arrested for the murder of his wife, which had occurred on the afternoon of September 15. Though noting his race, the newspaper article referred to the defendant, James Jones, as “an outstanding Negro.”

At the time of his arrest, Mr. Jones owned and operated a large ice business in Riverhead. It was reported that he did the work of three or four men, was frugal, industrious, and both mentally and physically “exceptional.”

The victim was described only as “Mrs. Jones”—no first name given. In one newspaper account, she was described as “a strikingly handsome mulatto” who was “prepared to leave her husband and family.” The article went on to state that she “had her belongings packed” on the day of her death.

The reports said that the Jones family had taken on two roomers that fall, Charles Johnson and G. F. Edwards. The pair had traveled to Riverhead from Brooklyn to conduct a shooting gallery at a popular local fair. According to the newspaper accounts, Mr. Jones returned from work on the afternoon of the 15th to find Mr. Johnson in the house alone with his wife.

Ms. Jones, who was “dressed for the street” with suitcases ready, according to the reports, was apparently having an affair with Mr. Johnson. The newspapers stated that Mr. Jones discovered the affair that afternoon and became “insane with jealousy,” slitting his wife’s throat with a pen knife.

Her husband, and the father of her seven children, denied his guilt, though he changed his recollection of the day’s events over time. It was the Joneses’ 11-year-old daughter, Virginia, who would be the strongest witness against her father. She testified that she heard her mother holler from the basement that Mr. Jones was cutting her throat.

During the trial, the prosecution claimed that Mr. Jones used a penknife to kill his wife, cut himself in the neck, and then threw the blade into a cookstove to burn. The knife was later recovered.

When Mr. Jones took the stand in his own defense, he claimed that he came home and found Mr. Johnson in his house. He testified that Mr. Johnson went downstairs with his wife, and that he heard Ms. Jones tell the boarder that she would not go with him. Mr. Jones then described hearing a scuffle and a shout, which prompted him to run downstairs, finding his wife dead.

A parade of prominent witnesses testified in Mr. Jones’s defense. They all attested to his excellent reputation. However, the defendant was still found guilty of second-degree murder.

While languishing in prison at Sing Sing Correctional Facility in Ossining, New York, Mr. Jones threatened a hunger strike and also attempted suicide a few times. At one point he secreted a blade from a pencil sharpener, putting it inside his mouth, and attempted to kill himself with it. Another time, jailers confiscated a bottle of poison hidden in a pie that had been sent to the prisoner Jones by his sister.

Eventually, he told guards that he was ready to confess.

Referring to his wife as “the woman,” Mr. Jones told authorities that they had quarreled that evening because Ms. Jones was going to leave him. He said that when he told her how much this hurt him, Mr. Jones stated that his wife laid down on the floor and said “cut my throat.”

So he did, he said.

One of the things that’s particularly interesting about this story is the issue of race, which was always discussed in the reports of the day in a way that would absolutely not be acceptable in present day. Another thing that’s notable about the reporting of the time is the indifference to the specifics of the victim—a black woman who was allegedly cheating on her husband, thus her name was not thought to be important enough to have ever been mentioned.

This would never happen today, unless the victim could not be identified. The story of Ms. Jones provides a fascinating look at change, and how that change has manifested itself, in print and in society, throughout the years.