When Paul Goldberger considers a work of architecture, style is the least important metric for greatness.

He looks for purity, directness and simplicity, but also appreciates complexity. He loves spatial invention, thought-provoking design — decisions that make visitors think about how they want to live — and he often finds himself responding emotionally.

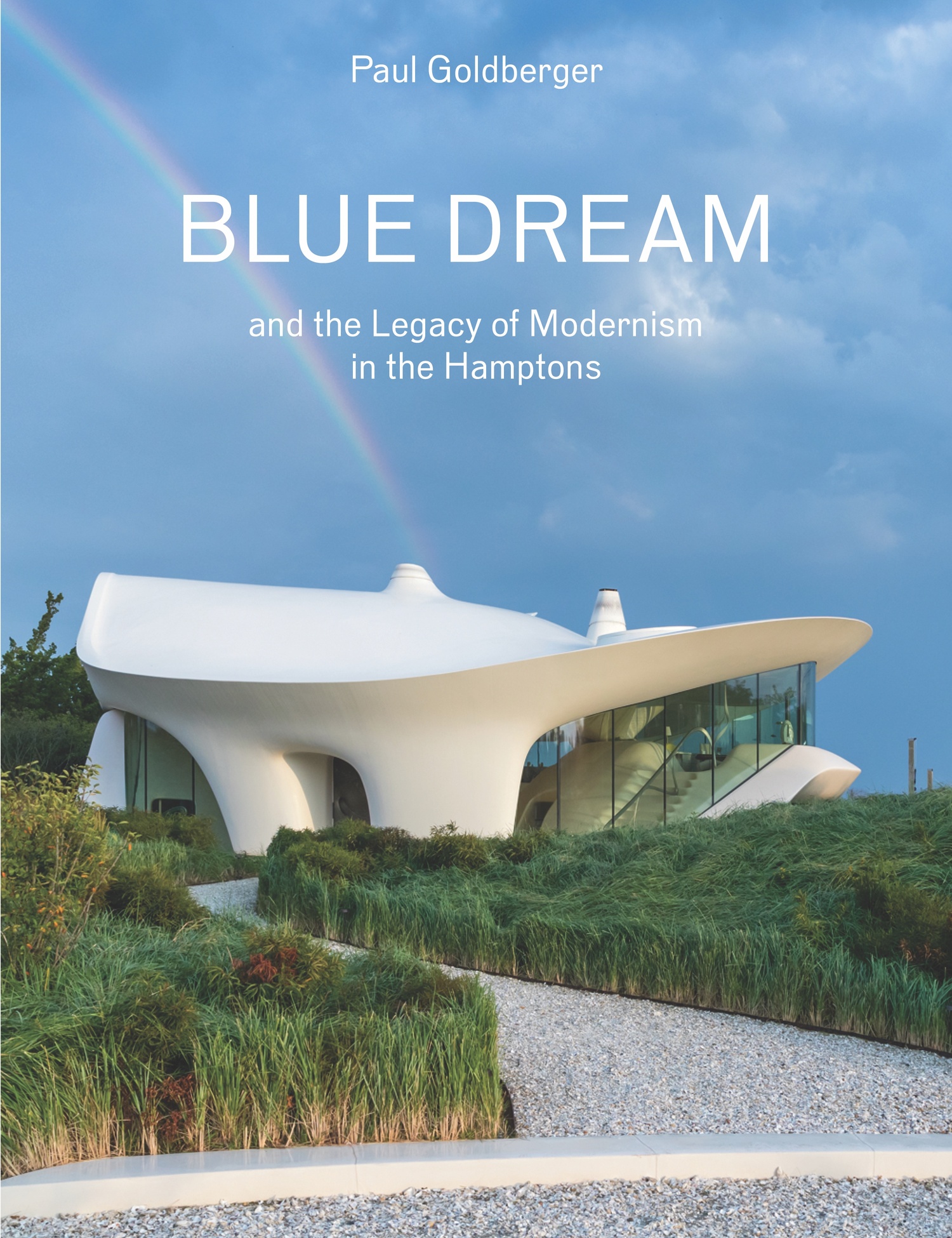

Standing inside “Blue Dream” — surveying the curving, avant-garde masterpiece nestled in the Atlantic Double Dunes in East Hampton — the Pulitzer Prize-winning architecture critic feels exhilaration. But as much as the home celebrates light, space and materials, it should not be a model, he emphasized.

“Frankly, if every house in the world were a unique work of art,” he said, “the world would be chaos.”

Goldberger’s newest book, “Blue Dream and the Legacy of Modernism in the Hamptons” — available September 13 — is an exploration of what most will never do. Through his prose and Iwan Baan’s photography, they chronicle this home’s nearly two-decade-long saga, its challenges and triumphs, and its place within the larger context of modern architecture.

But most of all, this is a story about relationships, the author explained — between clients, architects and builders — which rarely take center stage in architecture writing.

“If you write about architecture, buildings are always characters. I think it’s important not to let them become more important than people,” he said. “Buildings reveal a lot about people and people will reveal a lot about buildings. In the end, the relationship is itself the interesting thing.”

It was 2005 when Julie and Robert Taubman purchased a 5-acre parcel of oceanfront property at the end of Two Mile Hollow Road — with one parameter in mind for the house they would eventually build there. They didn’t want it to look at all like a traditional shingle-style home that was practically synonymous with the East End.

Additionally, Julie Taubman wasn’t interested in a large home. She just wanted it to be unique.

Inspired by her love of 20th-century furniture, architect Eero Saarinen’s aesthetic and her favorite building, the TWA Flight Center at the John F. Kennedy Airport, she and her husband decided they wanted to “recapture the energy of early modernism,” Goldberger writes in his book, “to feel the excitement of being on the cutting edge.”

And that is precisely what they did.

“There are a lot of people who are sophisticated and there are a certain number of people who are rich, but those don’t always happen in the same people,” Goldberger said. “When you find somebody who actually has the means and the wherewithal, but also has the knowledge of a connoisseur, or a serious student of design and architecture, that’s unusual.”

In the early planning stages, their search for an architect was exhaustive — they eventually interviewed 22 candidates — and the financial crisis of 2008 forced the couple to pause. Two years later, the Taubmans decided to work with the architecture firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro, which designed an innovative, undulating structure that broke away from the modern box.

In some ways, it felt like a structural experiment.

“I don’t think there’s any existing house that I can say, certainly not on the East End, that’s like it,” Goldberger said.

The biggest challenge, by far, was the sculptural roof. An international team, from England to the East End, oversaw its construction using a material called glass fiber reinforced polymers, typically employed for hulls of super yachts and fuselages of fighter jets.

“This was one of the first and definitely the biggest use of that material for a building,” Goldberger said. “It was molded and shaped into these various shapes that had been designed in 26 different pieces that were sized so that they can fit on a truck, and a convoy of trucks brought them from Washington State all the way across the country to East Hampton. That gives you a hint of how complicated this was.”

In the summer of 2016, the house was finally complete, with a one-of-a-kind interior that matched its exterior, featuring furniture by Saarinen, commissions by artist Joseph Walsh — who made a wide range of pieces, including the dining room table and master bed frame, and architectural details, like the hand-crafted wooden door handles — and metal staircase railings designed by architect Charles Renfro.

“We must have done 150 versions,” he reported in the book — the final version, Goldberger wrote, a “dance in metal.”

“You feel like you’re in a very organic, undefined space,” the author said of the home. “It does have a conventional floor, which is flat — for most of it — but the floor then curves up into the walls, which become the ceiling. So the whole thing feels, in some ways, like being inside an amoeba, or something like that.”

By the time the couple was ready to move in, two major design elements were not yet ready: Renfro’s stair railings and the custom bronze front door — a reproduction of Julie’s thumbprint etched into one side, Robert’s on the other. Temporary solutions were built in order to satisfy the certificate of occupancy, Goldberger explained, and after the latter was finally installed, it has proven to be especially touching.

Less than two years later, in January 2018, Julie Taubman died of breast cancer. She was 50.

“She was very happy in the end,” Goldberger said of her love of the home. “She felt she had gotten what she wanted, which was wonderful, and the sadness is that she didn’t get to enjoy it longer.”

For the first summer of Blue Dream, the couple welcomed friends and loved ones, and hosted dinners and parties. For their first Thanksgiving, they invited their extended families to dine around the table and celebrate the house. After his wife’s death, Robert Taubman and his children have continued to live there, and have not changed a single detail, Goldberger said.

“It reminds them of her in a very special way because it is so much her and what she wanted,” he said. “It’s a story that has a lot of poignancy to it because of her death, but it was her passion that made the house.”

The book does not only chronicle the history of Blue Dream, but it also serves as a tribute to Julie Taubman, her determination and unique vision, Goldberger said.

“This is not about saying every house should be like this. It’s almost the opposite,” he explained. “It’s saying that because every house shouldn’t and won’t be like this, let’s explore the one exception — the story of these people and what they did.”

Author and architecture critic Paul Goldberger and architect Charles Renfro of Diller Scofidio + Renfro will discuss “Blue Dream and the Legacy of Modernism in the Hamptons” on Thursday, August 24, at 7 p.m. at Guild Hall in East Hampton. Tickets are $20, or $18 for members. For more information, visit guildhall.org.