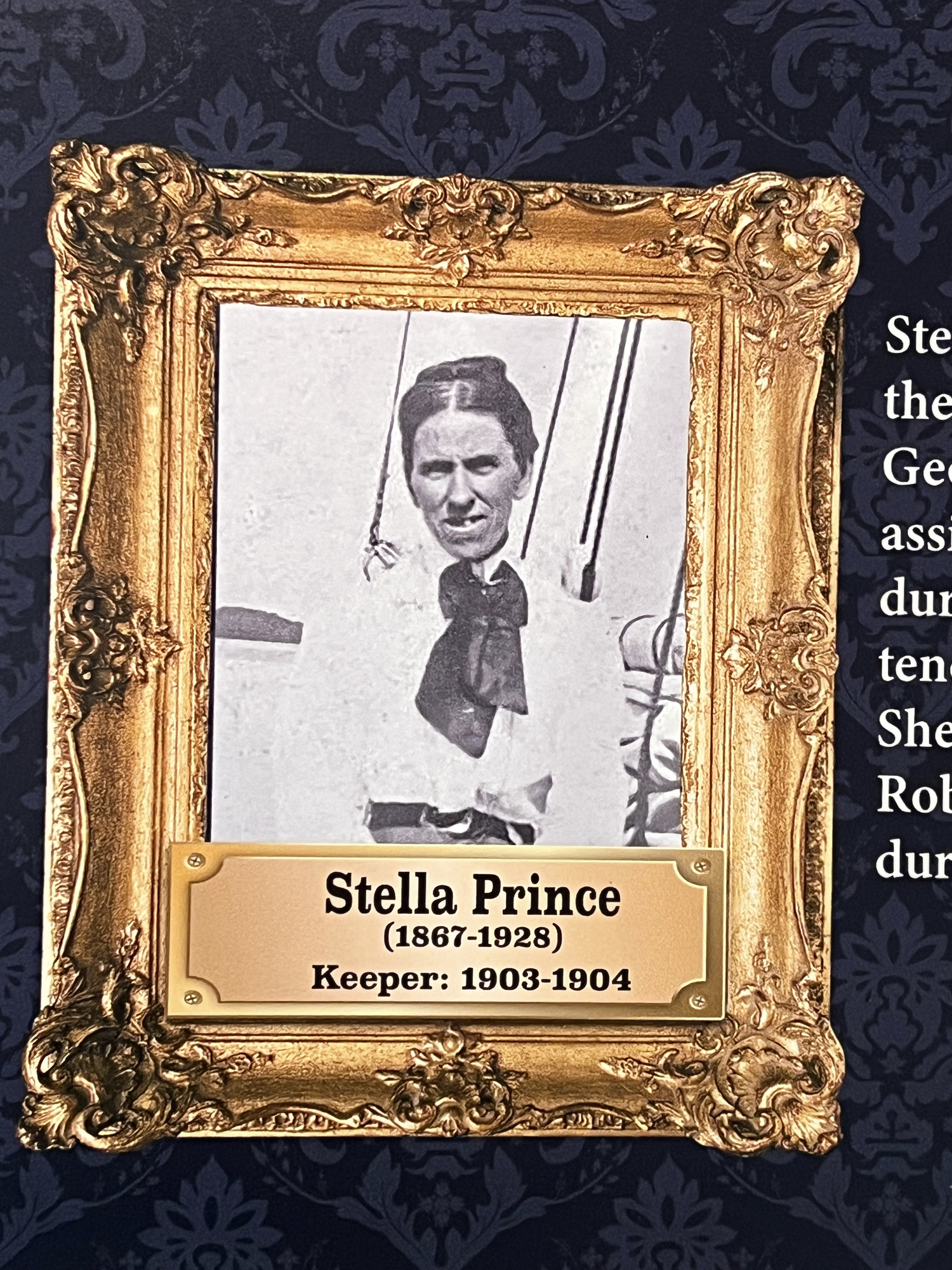

Stella Prince carried 40-pound cans of kerosene up a 28-step circular staircase, and two seven-step fixed metal ladders, at the Horton Point Lighthouse in Southold three times a day when she served as the acting assistant keeper there in the early 1900s.

The work was physically and mentally demanding. But Prince had grown up at the lighthouse, so by her mid-30s, nothing about the keeper’s duties would have been unfamiliar to her.

Some 120 years later, it would take the same kind of work ethic — this time, by a docent at the lighthouse museum — to see that Prince was finally recognized for her service.

Mary Korpi of Laurel didn’t set out to become Stella Prince’s champion, she said. It just kind of worked out that way.

After writing a novel based on Prince’s life called “The Lady Lighthouse Keeper,” Korpi said she just couldn’t put down the idea that Stella, as she refers to her, would forever be left off the official list of U.S. lighthouse keepers.

Prince’s name was absent from the historical record maintained by the U.S. Coast Guard due to a lack of documentation to prove her service.

“The gentleman at the Coast Guard told me, ‘Ma’am, everybody helps out at a lighthouse,’ but I told him, she didn’t just live there, she was paid,” Korpi said. “He needed documentary proof, but there were no payroll records before 1939 when the Coast Guard took over all the lighthouses.”

Korpi worked with local historians and librarians to try to track down some records on Prince. She visited libraries, historical societies and even petitioned the National Archives, with no response.

According to the Horton Point Lighthouse Museum, Prince was appointed to the post by then-President Theodore Roosevelt when head lighthouse keeper Robert Ebbitts took a bad fall and suffered a fractured femur. Korpi followed that lead all the way to the Old Orchard Museum on the grounds of Sagamore Hill in Oyster Bay, Roosevelt’s former home, but struck out there, too.

Coast Guard Historian Mark Mollan suggested Korpi’s request to the National Archives might get more attention if a librarian stepped in.

Jerry Matovcik of the Mattituck-Laurel Library agreed to help and contacted the archives on Korpi’s behalf. They got a response the next day, Korpi said, and, 10 days later, a document arrived listing Prince as a laborer at the lighthouse.

The single page, a payroll ledger, shows Ebbitts as the keeper earning $560 a year from 1901 to 1904, and Prince earning nothing but her title in the fourth quarter of 1903 and into first quarter of 1904.

It was enough for the Coast Guard.

“It took some months. I submitted the document in October of last year, and Mr. Mollan got it done in February of this year,” Korpi said during a recent interview. “But he listed her without a job title.

“For now, I’m accepting that, but I’m still searching for proof that she was, in fact, the acting assistant keeper.”

Korpi has been intrigued by Prince’s story since she first learned about it. A retired school counselor originally from Syosset, she and her husband spent summers on the North Fork for years before buying a year-round home in Laurel in 2017. “At that time, I was on a mission to get involved and meet people,” Korpi said.

Anxious to get involved in the community and its history, Korpi began volunteering as a docent at the Horton Point Lighthouse Museum in August 2017. Through that work she was introduced to the tale of Stella Prince.

“I love history, so it was immediately fascinating to me,” Korpi recalled. “I was reading everything I could find and talking to everyone I could think to talk to about her and the lighthouse.”

Korpi learned that Prince came to the lighthouse with her parents and sister at the age of 3 when her father was named assistant lighthouse keeper. A veteran of the Civil War, George Prince struggled in the years after his return home, more so as time went on. Still, in 1871, he was named head lighthouse keeper.

“Stella really rises to the occasion and takes on much of the responsibility for the lighthouse. Like in a farm family, everybody is expected to help out and pitch in and Stella did an enormous amount of that work,” Korpi said.

In 1896, George Prince was fired for cause — related to drunken misbehavior — and Ebbitts was named his replacement. Rather than leave with her family, Stella Prince stayed on to assist Ebbitts and his wife, Korpi said.

The more she learned about Stella Prince, the more inspired she became. At first, Korpi funneled her knowledge into drafting a kind of script to go through with visitors to the museum.

“I started out by making a trifold for myself to summarize the story so I could present it when I was at the museum,” she recalled. “Then, all of a sudden, I had two trifolds, and I said to myself, I think I’m going to have to write a book.”

Korpi spent the next few years researching, writing, rewriting and shaping “The Lady Lighthouse Keeper,” a book of historical fiction, which was published in February 2022.

The Cutchogue Writers Group, of which she is a member, helped workshop the book along with several friends and colleagues.

“It was my first book, and I would guess will probably be my only, but I loved doing it,” Korpi said. “I backed into this whole project.

“I set out to read a book, not to write a book.”

Horton Point Lighthouse Committee Chairperson Gillian Wilson is one of two officials who oversee the museum docents. She said she has been delighted to see Korpi’s journey as a new author and advocate for Stella Prince and the Horton Point Lighthouse.

“Most of our docents are happy to receive information. Mary is probably the only one I know who wanted to go out and find information,” Wilson said. “We are all just amazed and delighted at her persistence. It’s so good for the museum, and I hope it inspires more people to come to visit it.”

The Horton Point Lighthouse opens Memorial Day weekend, and is open Saturdays and Sundays from 11:30 a.m. to 4 p.m. Visitors can climb the same stairs Stella Prince did — weather permitting — and will be treated this year to refurbished exhibition of historical items, Korpi said.