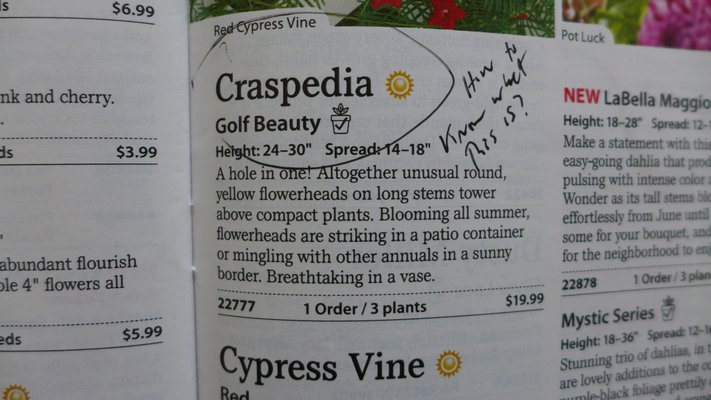

I received an email from a reader last summer with a picture of a plant, referred to as a “lily,” and a question about the plant. Turns out the plant wasn’t a lily at all—and that was part of the problem. The vast majority of gardeners use what we call “common” names to describe their plants. Unfortunately, there are even plant and seed catalogs that use only these common names, which are easy to remember but often misleading—and, also, often wrong.

So, here’s an opportunity to learn about your plant names and, in turn, learn much more about them and where they came from, and what they need to grow and thrive.

If you tell me you have a maple tree, my eyes glaze over. There are literally hundreds of types of maples, and when you say “maple” to me, I think of a generic plant with a generic form. But if what you really have is an Acer palmatum, I already know much, much more about the tree that’s on your mind, because I know that palmatum means that this species of maple, or Acer, is a Japanese maple, not a weed-like and invasive Norway maple (Acer plantanoides), or the maple that the delicious candy and syrup comes from, the sugar maple (Acer saccharum).

So, what’s in a name? Well, look back at the sugar maple. We know that the first part of the name, the genus, puts the tree in the Acer family. But then we go on to the species, or second part of the name, which in this case is saccharum, and we know much more about that tree, because in Latin “saccharum” means sugar.

Now, let’s go one step further. There is a grassy plant whose genus, or first name, is Saccharum. Any idea what this might be? Remember the Latin? The genus Saccharum is the grass (yes, botanically, a grass) also known as sugar cane.

Another case in point: Everyone knows the Christmas cactus, whose botanical name for ages was Schlumbergena bridgessi. And anyone who is familiar with this plant also knows that it rarely blooms at Christmas but quite often at Easter or Thanksgiving. It’s not the plant name that’s wrong, and the plant’s calendar hasn’t been corrupted by a digital virus.

Well, actually, the plant’s name is wrong. Turns out that many of the plants sold as Christmas cacti are actually the species S. truncata, which blooms around Thanksgiving, and S. gaertneri, which blooms around Easter. So if we knew what species we were buying, we’d have a better idea of why it’s blooming when it blooms.

Now, for many gardeners, botanical names are difficult to understand, but with a little explanation perhaps you can appreciate and understand them more.

The use of Latin binomials, the two words that describe the genus and species of a plant, dates back to around 1753. Carolus Linnaeus, a Swedish physician and botanist, at that time gave each species (specific group) known to him a Latinized generic name and a specific adjective—and thus began the identification of plants by genus and species.

The botanical name of a plant thus consists of two definite parts. To Linnaeus, a white rose was Rosa alba. The name Rosa indicates the affinity of the plant with all other roses. But the “alba” part of the name distinguished it from all others in the group. So, all the different roses would have Rosa for the first part of their identification. The second or more specific (species) part of the name indicates the individual kind of rose.

Rosa sinensis is a Chinese rose. How do we know that? Because we know that “sinensis,” in Latin, relates to Chinese. And, thus, Rosa Carolina is a rose from …? Right, Carolina. Rosa lancifolia would be a rose with a lance-shaped leaves.

We can carry this though to another genus, Dracaena. Many of us have or have had a houseplant in this genus. The most common is Dracaena marginata. Here, the species, or specific identifier “marginata,” reflects that this plant’s particular characteristic is that the foliage has a distinctive margin (marginata) that is often defined by hues of red.

Going one step further, we can look at Dracaens marginata picta. Here, we have the known genus and species, with the last word, “picta,” being Latin for “colored.” So, this would be a Dracaena with a red margin that is further embellished with other colors in the margin as well.

The botanical name is not only a name but often tells us something more about the plant: what it will look like when flowering, what other plants are its relatives, or the shape of its leaves, color of the flowers, its origin, habitat or who discovered it. In some cases, gardening and horticulture books will index the plants in the text by their botanical names, with a cross reference to their (most) common names as well.

Because common names, like lily, can be misleading (as in the French mulberry, which is neither French nor a mulberry), there is a need for an international nomenclature or taxonomy among plants and people working with plants. Spanish moss is neither Spanish nor moss, because we know from its scientific or Latin name that it’s related to, of all things, the pineapple.

Popular or common names can be indefinite and not very widely understood. Few in Russia or Japan would know what an English poplar is, but they might know it by its genus and species.

Another good example of this kind of name confusion can be found in weeds. In Texas, the careless weed is the same plant that, in California, is called the pigweed—but in New York and Illinois, the weed called pigweed is an entirely different genus and species. It was found that the careless weed of Texas was Amaranthus retroflexus, which is called redroot pigweed in Florida.

Why is this important? After all, a weed is a weed is a weed. Well, it isn’t. If it’s misidentified by its common name, and it’s an annual and not a perennial, that can have very important ramifications in controlling it.

So, here we are, in the dead of winter, and there’s a great learning opportunity.

L.H. Bailey, considered the father of American horticulture, wrote a book in 1933 called, oddly enough, “How Plants Get Their Names.” You can still buy it for under 10 bucks, and it’s a classic that all gardeners, young and old, should read. He explores hundreds of fascinating ins and outs of horticulture nomenclature. You’ll learn that the Jerusalem cherry grows nowhere near the Holy Land, and that the Spanish cedar actually grows thousands of miles from Spain.

There’s also a more recent book (1993 and 2003) by Bill Neal, “Gardener’s Latin: Discovering the Origins, Lore & Meanings of Botanical Names.”

Now’s a great time for gardeners to read—magazines and gardening columns from last year, seed and plant catalogs that are arriving, and a good book on plant names.

Keep growing!