James Brooks and his wife, Charlotte Park, once walked to work each day — from the back of their shingled cottage, the screen door of the porch closing behind them, along a 100-yard-long path edged in moss that connected their tiny home in the woods of Springs with a pair of studios where they both painted.

The floor of the 11 acres of scrub oak forest that surrounded them was flecked with bits of grass, dry leaves and more moss, a thick canopy of green overhead in the summer. By winter, the naked limbs of the trees cast abstract shadows on the ground that looked as if they could have leapt off the canvas of one of their paintings.

In the spring and fall, as the seasons changed, Park would have taken note of the evolution of plants and flowers in the landscape, and commented on the birds passing through, nesting or migrating. She made careful and thorough observations of the natural world around her, noted in dozens of journals she kept over the decades she lived in Springs — from walks in the woods, outside her studio, or watching out the windows from the house that had once been a fisherman’s shack, all of it subtly informing her soft and warm canvases.

Meanwhile, on the floor of his self-designed studio — with its jagged roof line and flood of natural light — Brooks worked on his monumental paintings, conjuring lines and forms and pools of color.

Together, he and Park created some of the art that helped define the nascent abstract expressionist movement in America and established Springs as an outpost of creative thought in the wilds of the East End.

But today, those buildings — the house, two studios and another outbuilding used as guest quarters — are boarded up, some with tarps on their roofs to keep out the rain and snow. Parts are in danger of collapsing in on themselves. When the Town of East Hampton acquired the 11 acres as open space back in 2013, the intention was to simply knock down the buildings that stood there.

That was until the Town Board learned of the history and provenance, and the legacy left by Brooks and Park, who died in 1992 and 2010, respectively. The town decided to preserve the buildings, recognizing the compound as a historic landmark, and dedicated $850,000 to their restoration.

In the ensuing years, neglect and vandalism have plagued the buildings to the point where the town is again considering their demolition.

In fact, a report from the town’s Community Preservation Fund last year recommends just that. An updated condition report is now in front of the Town Board, and the members of the Brooks-Park Arts and Nature Center — a group established to promote the preservation of the property — anxiously wait to hear, over the next week or so, what the town’s final decision will be.

In the interim, the group has been working to keep the preservation effort in the minds of the public by writing letters to local newspapers and, recently, holding a hike and presentation on the property that attracted about 125 people on a frigid February afternoon.

At the same time, they are developing a vision for the compound that celebrates the couple’s work and evokes the lives they led there.

“I like to imagine them walking with cups of coffee, out to their studios,” said Janet Jennings, one of the group’s members, as she stood just off the back of the residence and looked through the woods toward Brooks’s studio. “There was a lot of thinking that went on during those walks.”

The heart of that residence actually got its start on a bluff overlooking Fort Pond Bay in Montauk many years ago. While Brooks and Park were aware of the burgeoning art scene in Springs — their friends Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner had already set up residence there by late 1945 — the couple headed farther east and, in 1949, bought a cluster of three buildings west of Navy Road overlooking the bay.

It was “where the maritime light and coastal environment influenced the development of their lyrical abstract imagery,” wrote Helen Harrison, art historian and director of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center, in a presentation to the town supporting the preservation effort.

There, Brooks and Park painted in a barn, which had been converted into a his-and-hers studio space, which sat farther down the bluff, close to the shore, Harrison said. Their home was a tiny fisherman’s cottage that perched a bit higher up, and the third building was a storage shed they had converted into a sort of guest quarters for when their friends, like Pollock and Krasner, made the trek east for a visit.

Calamity struck the little nest of buildings when Hurricane Carol made landfall in Montauk in August 1954. The house and storage shed survived, but the studio was blown in half.

Owning the buildings, but not the land upon which they sat, the couple decided to decamp to 11 acres of woodland they had bought on Neck Path in Springs and, in 1957, floated the house on a barge across Napeague Bay to a landing near Louse Point — perhaps underscoring a practicality and frugality that was in their character. It was then trucked by Kennelly House Movers of Southampton to their Springs property.

Artist friend Ibram Lassaw recorded the move in photographs, which show the house up on skids with a red truck preparing to pull it to its resting place. The little shed that became a guest house soon followed, eventually serving as a studio for Park. This moving and reusing of buildings was, at one time, much more common on the East End than it is today, and very much in keeping with the way the couple saw their relationship to the world.

“When looking at the property, it’s kind of important as it indicates what their basic attitudes were,” said artist Mike Solomon, the son of abstract expressionist pioneer Syd Solomon, who spent much of his youth visiting with Brooks and Park.

“Where they positioned the house was intentional,” he added. “It’s on a very long property, and most people would put the house closer to the street. But as the studios are spread throughout the property, there are big spaces in between, and they would have a long walk to work.”

They lived simply, perhaps due equally to economics and personal choice. They enjoyed dinners with their fellow artists, at times maybe having parties with 10 or more, but more likely smaller dinners with three or four other guests.

“They were really gentle, quiet people,” Solomon said. They were “enamored of the peace and calm” of Montauk, he said, and sought the same in Springs.

“They were social, but they were really centered,” he added. “They lived an extremely simple life, ate simply and didn’t have a lot of things.”

Indeed, photographs of the interior of the house show spare furnishings. There was a handful of pieces of modern furniture in the living room, a couple of slender chairs and a cot served as a couch.

The kitchen area from the house’s days in Montauk is a portrait of simple domesticity: a joyfully eclectic collection of coffee mugs and teacups, and plates and platters stacked along a half wall that separates the kitchen from the rest of the living area. For want of cupboards, pots and pans hung on hooks along the wall.

And to underscore the remoteness of the home, the handle of a hand pump at the sink — the sole source of fresh water — is just visible, curling up above the kitchen’s half wall.

For much of the time Brooks and Park were in residence in Springs — which was seasonally until an addition was made to the house in the early 1980s — the home lacked any winterizing, except for a wood-burning stove. In photos, it is clear there is no insulation in either the ceiling or the walls. Studs and beams are exposed, and the back of the clapboard sheathing is clearly visible.

But it was home, and it suited their nature, said Solomon. “The way they occupied their minds was centered in nature,” he said.

Perhaps the greatest evidence of that is in the logs that Park kept almost daily, year after year:

“Saw our first Hairy woodpecker at suet — hung 5 days ago,” she wrote in 1974.

In 1994: “Either a sharpshin or Merlin swooped in — birds scattered — he landed on wire for suet — only showed his back with black stripes on tail. Couldn’t see front.”

“Buck on studio road early, the 2 young deer on edge of lawn. Open shade and shutters all fled! Redhead chipping ice on rear bath again,” she wrote in 1999.

“Charlotte really loved walking around in nature,” observed Solomon. “Her studio was really the whole property in some way.”

In addition to a bedroom space in the house, Park did in fact have a formal studio — the little storage shed from Montauk — while Brooks painted largely in his studio in New York. Later, she moved into yet another older building shuttled onto the property.

For a few years after they settled onto Neck Path, the couple painted in the house they had moved there. Brooks’s first actual studio on the property was a building they sort of found on the side of the road. This was the former Wainscott Post Office — or at least a part of it.

“They drove by on the highway and saw it sitting there,” said Solomon, “almost as if someone said, ‘Here, take it,” although there may be evidence the couple did, in fact, pay for the structure.

Again, they had the building trucked over to their property, and the addition helped to begin the campus that became their working and living environment. Brooks used this building as his studio until he designed his own in 1960, and Park took over the old post office building, with its wood shiplap siding. And the little shed from Montauk returned to its use as a guest house.

Brooks’s studio is perhaps the most distinguished building on the property, with a modern design that borrows from one of the East End’s vernacular styles. Ultimately, it became a configuration that one architectural historian described as “genius.”

“The saltbox was the iconic structure here,” Solomon said. “He started with that. A good idea to get a good amount of cubic space is to take a saltbox.”

Then, a challenge presented itself in the design: how to diffuse the light evenly throughout the space and down to the floor, where Brooks mostly worked, Solomon explained.

Traditionally, a salt box features a roof that, on one side, starts above the first story of a two-story house, then rises to a peak against the other side of the roof that comes down only as far as the top of the second story, giving the design a distinctive silhouette. Running a row of windows across the roofline of the shorter roof would give a lot of light to the space below. But, observed Solomon, Brooks understood enough about the way light would fill the space to realize he would need another peak, in the center of the building, to create the flow of light that would diffuse evenly all the way down to the floor.

Thus, the final design of the studio features two peaks, creating a sawtooth effect on the roofline, with a bank of 6-foot-high windows across each peak. The result is a roughly 1,300-square-foot space with a minimum ceiling height of about 12 feet, filled with evenly diffused north light.

“He was a brilliant guy,” Solomon said. “He educated himself, he knew art history. That idea [of sourcing light] goes back hundreds of years. He understood the general concept, but also the local genre.”

The studio was constructed by a local builder from a drawing sketched by Brooks himself. Solomon said the artist was very aware to face the studio to true north, not magnetic north, to get optimum light. “He knew how the light would change as the year progressed,” he said.

There was no electricity at first and the studio was heated by a wood stove. Still, it would get cold enough for the couple to leave during the offseason. “About the time Thanksgiving rolled around, they would pack up and head back to the city,” Solomon said.

That was until improvements and additions were made to the house — one in the 1970s for storage space and, the other, a bedroom, in the 1980s — that allowed the couple to spend the whole year in Springs. But those were the days when Park walked the paths on the property noting hungry woodpeckers, and Brooks yanked on the pulley system that cracked open the windows soaring 15 feet above his head to let in air to cool his studio.

Today, the effort is to preserve the buildings and, with them, evidence that tells the story of an artist couple who helped define an art movement and how they lived and worked.

“We are at the intersection of art and nature; the two are woven together,” said Marietta Gavaris, one of the driving forces behind the Brooks-Park Arts and Nature Center. And what the group hopes to explore in the proposed facility is how a life fully integrated with nature reveals itself in art.

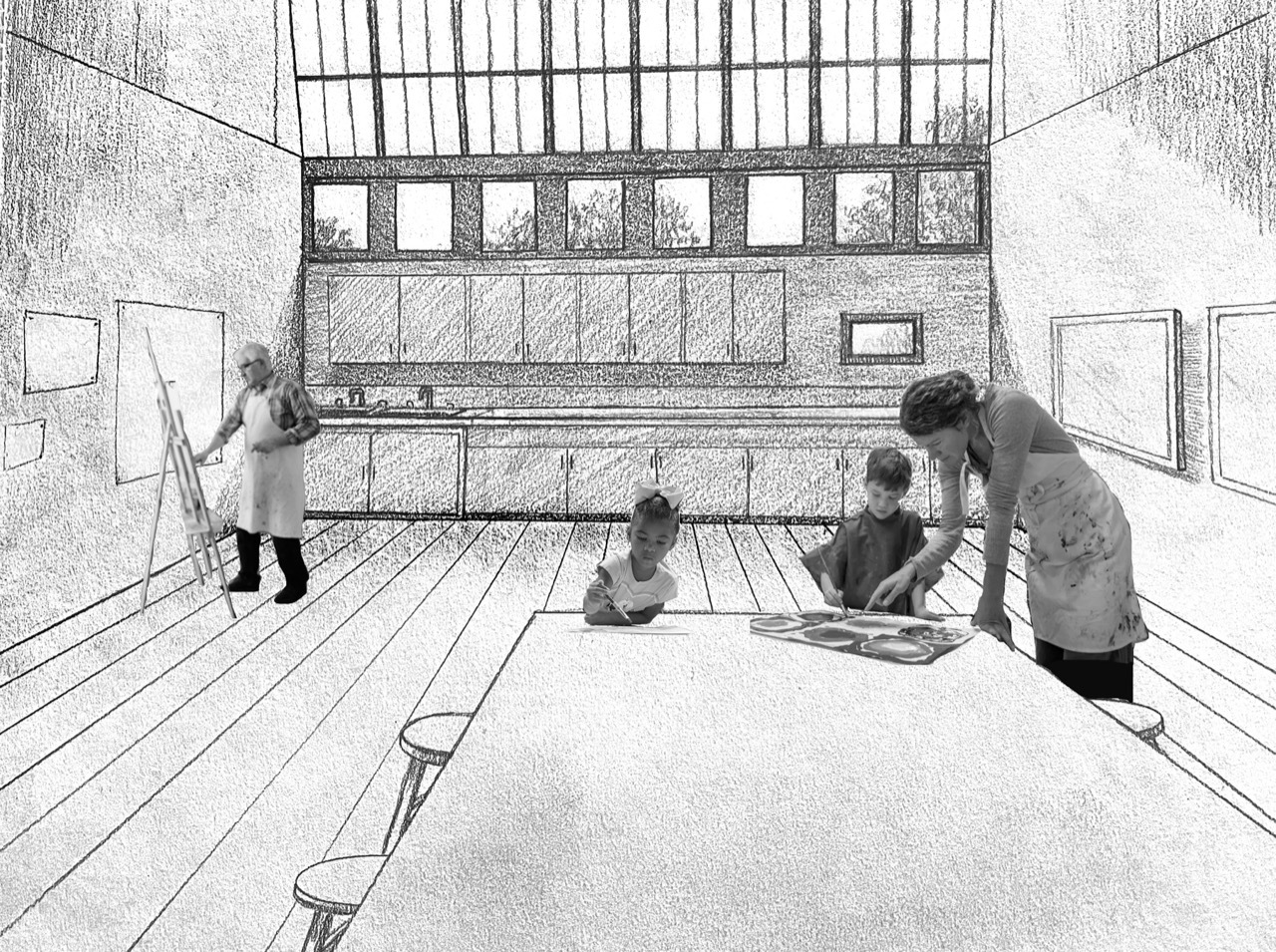

Both Gavaris and Jennings — who, when walking the property, exhibit a mixture of purpose-driven exuberance with a tinge of foreboding — say that the final plans are very much up in the air. But a vision in broad stokes imagines a museum with study opportunities on the life and work of Brooks and Park.

“I can imagine workshops in the studio,” Gavaris said, “exhibits and art demonstrations.”

Jennings said she could picture outdoor readings and talks during the summer in the expansive area between the house and studios. They say it should be a publicly accessible place.

Both women pointed out that if the site is preserved, it would join a small group of other former artist studios and residences that have been preserved in Springs. There is the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center, which includes the artists’ home and studios that are open by appointment. Also, the former John Little studio, which is now the Arts Center at Duck Creek, hosts periodic exhibits. Willem de Kooning’s original studio is protected and managed by the family foundation, and is available for special study on the artist only through the foundation. Elaine de Kooning’s studio is likewise available for special study through its private owner.

Also in Springs is the Leiber Museum, which features the work of famed handbag designer Judith Leiber and her painter husband, Gerson Leiber. And nearby in Napeague is the home, studio and archives of artists Victor and Mabel D’Amico.

The Brooks-Park house and studios, Gavaris and Jennings argue, would be an additional valuable resource for those exploring the ascent of abstract expressionism — and art in general — in the Springs area.

“But it’s not just for art lovers,” Gavaris stressed, adding, “Maybe we could use one of the smaller buildings for hikers, or bird enthusiasts, and learn more about our natural landscape.”

Indeed, the property is well suited for nature study and hiking. On the 11 acres is a pair of short trails that amble through the woods. One leads out to Red Dirt Road, just across from the town’s George “Sid” Miller Trail, which leads through a local oak forest across a rolling, glacially carved landscape. It crosses and links with several other trails, including the Paumanok Path, the 100-mile trail that runs from Rocky Point on the North Shore to Montauk Point.

After Brooks died in 1992, Park lived and worked at the property alone. Solomon, who had spent so much time on the land as a child, returned toward the end of Park’s life to help the widow chronicle her and her husband’s work, and create a database.

He remembers the simple lifestyle he saw in his youth was still very much alive when he returned as an adult.

“At lunch, she’d pop a couple of cans of Campbell’s soup, maybe add some seasoning, maybe some celery and a piece of toast,” Solomon recalled.

“Everything they did had a light touch,” he added. “It was what they tried to do: touch the earth lightly.”

Two upcoming exhibits will highlight the work of James Brooks and Charlotte Park. “Charlotte Park: Works on Paper from the 1950s,” will run from Saturday, March 12, through April 23 at the Berry Campbell Gallery in New York, followed by “James Brooks: A Painting is a Real Thing” from August 6 to October 23 at the Parrish Art Museum in Southampton. For more information, visit berrycampbell.com or parristhart.org.