When Kaylie Jones was 16, her father, James Jones, the author of “From Here to Eternity,” and “The Thin Red Line,” died of congestive heart failure in Southampton Hospital. The year was 1977 and he was 55.

Ms. Jones, who adored her father, was devastated. Her despair was amplified because she had been raised with no belief system and her mother, Gloria Jones, was an abusive alcoholic who had treated her cruelly all her life.

But in Ms. Jones’s recently published memoir, the chapter that recounts her father’s death is called “The Birth of a Student.” With nowhere else to seek solace, she turned to literature. She started by reading his novels the summer after she graduated from East Hampton High School and then, at Wesleyan University, she found mentors and soon began to write her own stories.

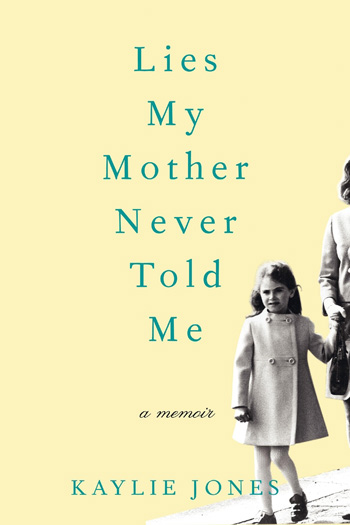

“I probably never would have written a word if he had lived,” Ms. Jones said over tea and scones on a recent Thursday in Manhattan. Ms. Jones, now a professor of creative writing for Stony Brook Southampton’s MFA program, was about to leave for a flight to Ohio to give a reading from her memoir—her fourth book and first crack at non-fiction—called “Lies My Mother Never Told Me,” which was published in August.

“I wrote it because I had to,” Ms. Jones said. She had never considered writing a memoir until eight months after her mother died in 2006. Ms. Jones was walking her dog with her friend Susan Cheever, talking about what she was thinking of writing, and her friend told her that it wasn’t going to be a novel, but a memoir.

“The idea was so unbelievably terrifying, so I thought, well, if it’s that terrifying then I should do it,” she said. Children of alcoholics grow up knowing they should not talk about what goes on at home, she said, and they don’t acknowledge the problem. “You certainly don’t do the dirty laundry in public,” she said.

The memoir offers a brutally honest portrait of the cruelty and alcoholism of her mother and Ms. Jones’s own struggle with alcoholism, sharing space with stories of a childhood among her parents’ famous literary friends and their wild days of partying, first in Paris and then in Sagaponack.

“I didn’t withhold, or hold back or soften the blows as a writer,” Ms. Jones said. She felt that she had to tell the truth as she knew it, as her father had taught her, and tell it with objectivity.

But it is also an inspirational story, as Ms. Jones was able to quit drinking more than 17 years ago and find love, get married, have a daughter, start teaching and become a black belt in tae kwon do.

Within a month of the book’s release, Ms. Jones said she received long, intimate e-mails from strangers who have dealt with alcoholism and who identified and found inspiration from her story. She said that some people were angered by the book, because it showed her mother’s monstrous side, but she was okay with that and had not feared such reactions.

“I think everyone should live as if it’s an open book,” Ms. Jones said. “You should have to answer to your behavior, especially toward your children.”

Before even deciding to write the book, Ms. Jones said she had a good understanding of the sickness that is alcoholism, as she had done extensive research and undergone therapy on its symptoms and the struggles that children of alcoholics face. So by the time she sat down to write, she said, she already had identified and learned how to deal with the rage she felt in her early adulthood and had felt most keenly when she stopped drinking.

When asked whether the process of writing the book allowed her to forgive her mother, she said, “Forgiveness is God’s job. I’m not God, it’s not up to me, I’m just telling the story.”

“It’s easier to live without rage and resentment, so you have to face it and get over it. But is that the same thing as forgiveness? I don’t know.”

Even though it was Ms. Jones’s first book of nonfiction, she said she did not get too bogged down in trying to get the details just right or remembering exactly what happened. She has daily journals from her whole life, she said, and an excellent visual memory. To paint her mother’s picture with words was easy, she said: she just told the stories her mother, a renowned charmer, was famous for. “It was like pushing a tape recorder,” Ms. Jones said. “I thought, I can’t do justice to her through my eyes, but I can tell you her stories.”

Ms. Jones started writing the book in February 2007 and finished in April 2008, which she said was quick for her. She wrote every weekday for three to four hours in the morning, she said, writing without an agent or editor because she did not want any outside influence until she finished.

“I pretended it was a novel,” Ms. Jones said. “I went with the premise that I’m the I, but I the character is a different person than me, so I could be objective.” The same premise is at work when Ms. Jones looks at her father, she later said when asked if she had initially compared herself to him when she started writing.

“Do I compare myself to Ernest Hemingway or Katherine Anne Porter?” she asked. “There’s a duality. There’s my father and there’s James Jones, the writer.”

Ms. Jones said that growing up, she had never wanted to be a writer. “I thought it was an awful life. I never thought I’d have the discipline to do it.”

But that changed by the time she got to Columbia University, where she pursued her MFA in creative writing the year after she graduated from Wesleyan. “I knew it was what I was going to do. It was a calling, like joining the Army, something you have to do.”