By Annette Hinkle

“The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

With those few words, the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified 100 years ago and women coast to coast officially won the right to vote. For women and the men who supported their struggle for suffrage, it was a long and hard fought battle, and it would take almost 50 years more before Black women were assured their access to the polls as well.

First introduced to Congress in 1878, the Nineteenth Amendment passed the House of Representatives on May 21, 1919, with the Senate following suit on June 4 of that year. On August 18, 1920, Tennessee became the last of 36 states needed to ratify the legislation, and on August 26, it was officially adopted, becoming the law of the land 40 years after its introduction and three years after New York State had granted women the vote.

Now, a century later, in this summer of protest and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement with a contentious presidential election looming large, it’s clear that exercising one’s right to vote is more important than ever, regardless of gender, ethnicity or religion. It also seems an opportune time to look back at an earlier era when large groups took to the streets to advocate for the rights of a disenfranchised segment of the U.S. population — its women.

[caption id="attachment_102600" align="aligncenter" width="600"] Women’s Political Union Suffrage tent at the Suffolk County Fair, Riverhead, 1914. Collection of East Hampton Historical Society.[/caption]

Women’s Political Union Suffrage tent at the Suffolk County Fair, Riverhead, 1914. Collection of East Hampton Historical Society.[/caption]

To mark the occasion of the ratification of the amendment, on Saturday, September 19, the East Hampton Historical Society will present “Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence,” a one-day exhibition at the Clinton Academy Museum. On view will be several suffrage posters from a larger installation recently organized by the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. Also on display will be objects from the East Hampton Historical Society’s own collection that tell the story of women’s suffrage on a more local level.

The historical society’s collaboration with the Smithsonian began earlier this year with “Water/Ways,” a traveling exhibition at the Clinton Academy. The museum was chosen by the Smithsonian as one of just six sites in the United States to receive the exhibition, which had to close after two weeks because of the COVID-19 pandemic in March. East Hampton Historical Society’s executive director, Maria Vann, explains that when “Votes for Women” came up as a possible second collaborative exhibition with the Smithsonian, she jumped at the opportunity.

“Since ‘Votes for Women’ couldn’t be seen in D.C. as much with the pandemic, they created a free poster exhibition that any place that wanted to do it could,” explained Vann. “Of course, we wanted to do it. It’s the year of the election. We’ll try it for one day just to get people in for the anniversary.”

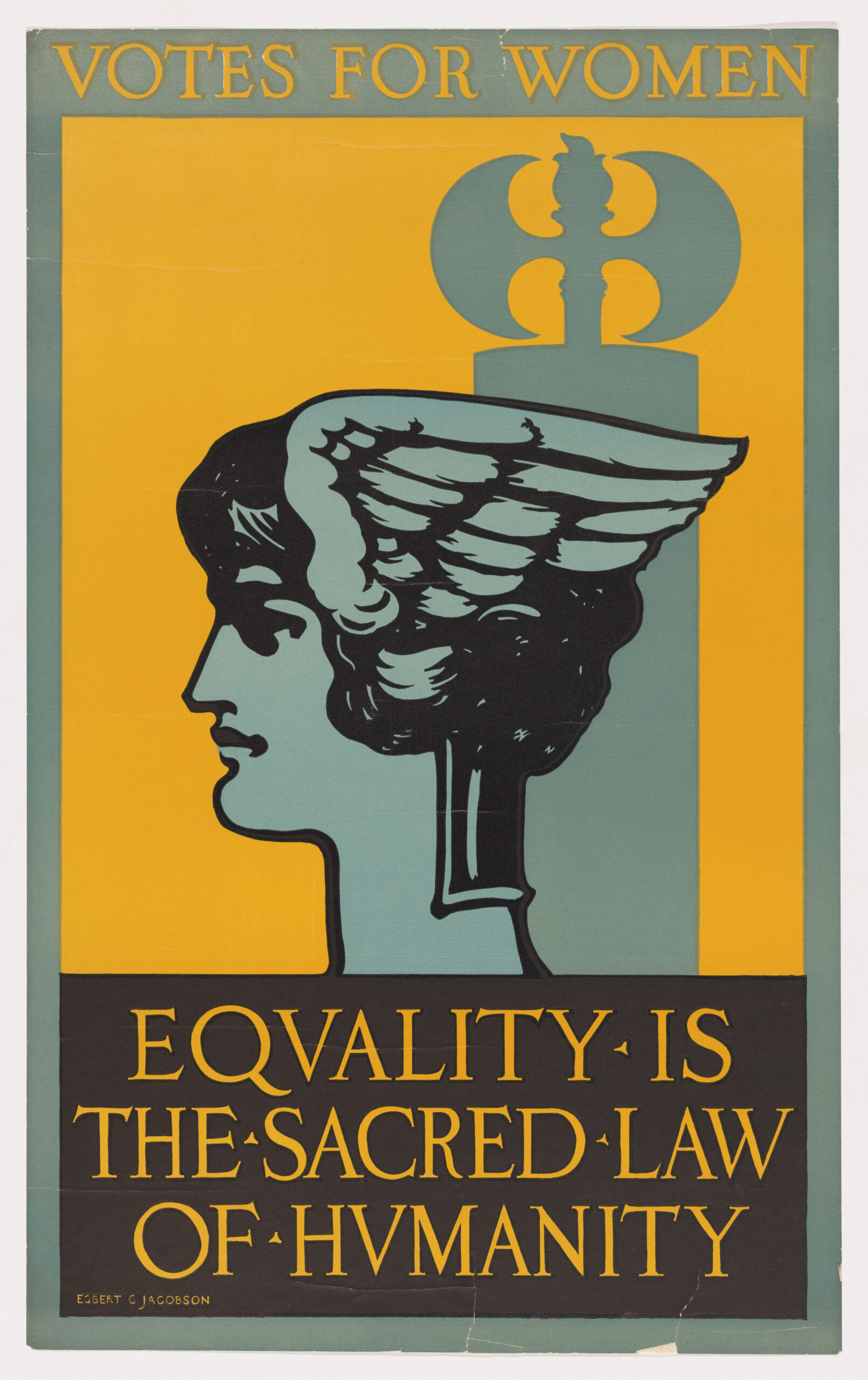

[caption id="attachment_102601" align="alignleft" width="378"] A Votes For Women poster from the exhibition of the Smithsonian Institution.[/caption]

A Votes For Women poster from the exhibition of the Smithsonian Institution.[/caption]

When asked why the historical society opted to show the pieces for only one day, Vann explained that it was a matter of staffing.

“We have a protocol for timed tickets and tried to squeeze it into a celebratory day,” she said. “We’ve connected with League of Women Voters about being a part of this to hand out voter registration. We have a lot to do, but we have a small but mighty staff and we didn’t want to miss this. We felt it was an easy lift to do.”

The Smithsonian posters that will be on view at the Clinton Academy are all from the women’s suffrage era and accompanied by text panels from its larger exhibition that summarize the timeline of the Nineteenth Amendment as well as the places and events instrumental in women’s fight for the vote.

“What we’re doing is supplementing it with objects and photographs,” said Vann, noting that the Smithsonian materials are the historical society’s to keep. “I think it worked out really nicely. It’s the type of exhibit that fits the space well and we can support social distancing, but also get the information out there.”

“This is a traveling exhibition. It’s small, beautifully done and great with graphics,” added Richard Barons, chief curator of the East Hampton Historical Society. “We are augmenting the Smithsonian’s scripted panels with several dozen historic photographs that illustrate both Long Island suffragist parades and activities as well as events in New York City and Washington, D.C.”

Barons notes that the exhibit will include about two dozen Long Island protest photographs as well as a selection of photographs by Durell Godfrey taken during East Hampton’s 2017 League of Women Voters march on the anniversary of New York State’s successful vote for women’s right to vote.

Barons explains that the suffrage protests of the early 20th century often centered on an array of unusual transportation modes — automobiles, wagons and even dirigibles — with women at the controls to highlight the fact that they were capable of doing anything men could do. One 1916 publicity stunt involved two New York suffragists in a biplane who planned to “bomb” President Woodrow Wilson with pamphlets in support of women’s suffrage as he made his way down the Hudson River on his yacht en route to a lighting ceremony at the Statue of Liberty. High winds forced the women to abandon their mission and they had to ditch the plane in a Staten Island swamp, and though the pamphlets remained undropped, the spirit of the suffragettes didn’t waiver.

But perhaps in terms of this exhibition, most exciting for Barons is the recent gift to the historical society of two pieces of original “Votes for Women” ceramics that were made for socialite Alva Vanderbilt Belmont, a major figure in the women’s suffrage movement.

Barons explained that the objects — a luncheon and soup plate — were used by Belmont at one of two well-publicized American Suffrage luncheons held at “Marble House,” her Newport, Rhode Island summer cottage, in 1909 and 1914. Over 1,000 women attended each of the events where the “Votes for Women” pattern lunch service was used. This same pattern was also used at the lunchrooms at the Political Equality Association headquarters in New York City.

“These rare original plates have just been given to the East Hampton Historical Society and will go on display for the first time at the special exhibition,” said Barons. “When it comes to tactile objects, I think these are two of the greatest you could imagine, and came through a bit of serendipity through a couple in Springs.”

[caption id="attachment_102602" align="aligncenter" width="600"] East Hampton Historical Society will present “Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence,” a one-day exhibition at the Clinton Academy Museum. Photo by Dana Shaw.[/caption]

East Hampton Historical Society will present “Votes for Women: A Portrait of Persistence,” a one-day exhibition at the Clinton Academy Museum. Photo by Dana Shaw.[/caption]

He explained that the mother of one of the anonymous donors of the plates lived on Long Island’s Gold Coast in the early 20th century and was very involved in the suffragette movement. She had been invited to one of Belmont’s famous Newport luncheons.

“These plates have attribution of having come from one of the luncheons,” said Barons. “They are these deliciously worn, proper plates with proper markings and they have just been added to the collection. As far as I know, they’ve never been shown before.”

Though much of the action in the Long Island women’s suffrage movement took place further west, Barons notes that East Hampton women were very active in advancing the cause locally.

“Upper class women were involved in the movement and they felt they were doing it for the underserved people,” said Barons, who notes that Camp Wikoff in Montauk, where Theodore Roosevelt and his “Rough Riders” came to recover in 1898 after the Spanish American War in Cuba, seems to have marked the beginning of woman’s activism in East Hampton.

The Montauk soldiers were not only suffering from war wounds, but many were also battling illnesses like yellow fever, typhoid and malaria, and the local women stepped in to help ease their pain.

“They were making bandages, trying to raise money to buy medicine, turning barns into convalescent houses,” he said. “There were at least five private hospitals started out here for people who were ill from Montauk. The editor of the East Hampton Star at the time said the women and the organizations getting together and playing political roles is a turning point and ‘I can’t imagine this will burn out. We should watch our women and see what happens.’

“The whole concept the suffrage movement gets really big, but all these women had been doing these things for 10 years,” he added.

Among those women was May Groot Manson (1859-1917) who had been involved with aiding Camp Wikoff soldiers and later became perhaps the most instrumental leader of the local suffragette movement. A wealthy East Hampton resident, she was the head of both the Woman Suffrage League of East Hampton and the Women’s Political Union of Suffolk County, and she frequently hosted women’s suffrage meetings at her home, which still stands on East Hampton’s Main Street.

Arlene Hinkemeyer, vice president of the League of Women Voters of the Hamptons, has done extensive research on Manson and helped to craft the language that appears on a historic marker that was dedicated to honor the suffragette in front of her former home in June 2017.

Hinkemeyer notes that Manson was active in many high-profile suffrage events in New York City and in August 1913, organized a large suffrage rally that began at her East Hampton home and marched down Main Street to the village green. The main speaker at the event was Harriot Stanton Blatch, daughter of pioneering women’s right activist Elizabeth Cady Stanton. She adds that the East Hampton rally came on the heels of big suffrage parades held that year in Washington, D.C., and New York City in March and May, respectively.

“Another big East End suffrage event, detailed in a New York Times article of June 8, 1915, was a Suffrage Torch Relay Crusade from Montauk to Buffalo,” explained Hinkemeyer. “Mrs. Manson started with the torch in Montauk Point, motored across Long Island holding open air meetings along the way and then handed it over to Louisine Havemeyer who took it to New York City.”

While well-connected women like Manson were vocal and active advocates of women’s suffrage, interestingly enough, not all women supported their own right to vote. Vann explains that anti-suffrage women were often wealthy and opposed to the idea of newly-arrived immigrants being allowed to vote, especially those who were not considered “white” at the time, primarily uneducated Irish and Italians.

“I’ve voted in every election, and I’m the mother of grown women who say this is a privilege my grandmother didn’t have,” said Vann. “There’s an Elizbeth Cady Stanton quote in the exhibit that’s profound to me: ‘I would have girls regard themselves not as adjectives but nouns.’

“We’re not always seen as nouns. Recently, there have been comments in the news that maybe we should go back to one vote per household,” added Vann, referring to statements made recently by RNC speaker Abby Johnson, who also advocated for husbands having the final say on what candidate a household supports. “People who talk about women being ‘given’ the right to vote — that shows where power lies.

“It’s about changing society’s mindset,” Vann said. “Women’s stories, like African American’s stories, are everyone’s story. That’s the key. Women fought for the right to vote, but there had to be a heck of a lot of good men behind them, too.”

“Votes For Women: A Portrait of Persistence” takes place at the East Hampton Historical Society’s Clinton Academy Museum, 151 Main Street, East Hampton, on Saturday, September 19, from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. Richard Barons and Arlene Hinkemeyer will be on hand to talk about women’s suffrage on the East End and answer questions. Pre-registration is required for admission. Email info@easthamptonhistory.org or call 631-324-6850 ext. 4 to register for an assigned timed entrance.