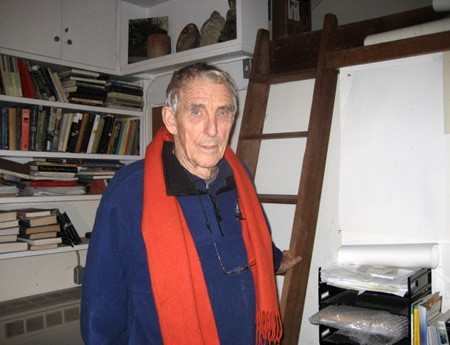

Welcoming an interviewer to his studio at the edge of a small orchard on his Sagaponack property in December, the writer Peter Matthiessen sat at a simple L-shaped wooden desk that runs along one wall and part of another.

The tall and wiry Mr. Matthiessen, 81, was attired in his sweats, having just returned from a workout at a gym in Water Mill. Acknowledging that he was pleased to have won the 2008 National Book Award for his novel, “Shadow Country,” he added a qualifier: “I believe I am the only writer to win this award in both fiction and nonfiction categories.”

Mr. Matthiessen’s connections to the East End of Long Island and Sagaponack in particular are strong and enduring. He summered with his family in the East Hampton area in the 1940s. After graduating from Yale in 1950 and spending some time in Paris, he lived in Springs for three years, working as a commercial fisherman out of Montauk.

Fifty years ago, when land was cheap and there were still plenty of lots available, Mr. Matthiessen bought his Sagaponack place. Gradually he coaxed the existing ramshackle buildings and chicken coop into a livable shingled house.

Since then, the author of eight novels, one book of short stories, 19 nonfiction works, member of the American Academy of Arts, recipient of multiple awards, naturalist and environmental activist has remained a resident of the hamlet. Mr. Matthiessen befriended, fished and went ice boating with the local men, and sent several of his children to the little red schoolhouse in Sagaponack. Though he decried the wanton destruction of the area, and once threatened to move to Alaska, he stayed put. He actively opposed the formation of an incorporated village of Dunehampton and favored the recent incorporation of Sagaponack.

He said, “Some years ago, I was involved with ZONE, a local and anti-development organization, which had mixed success.”

Reading, especially fiction, and writing have been part of his life since childhood. Mr. Matthiessen said, “I loved to read as a kid, as did my father. At Yale, where I majored in English literature, I discovered Dostoevsky and other Russian novelists.”

After graduation, Mr. Matthiessen published a number of short stories. But needing a steady income to support his family, he reluctantly turned to nonfiction and what he knew of the world. He had experienced the glories of nature as a young birder and fishing on his father’s boat.

“I knew boats and birds,” he said. “It was that simple.”

His articles appeared in Holiday Magazine, Sports Illustrated, and The New Yorker, where he worked closely with editor William Shawn.

As Mr. Matthiessen traveled the world, he jotted down his observations in a notebook tucked in a shirt pocket. These barely decipherable scribbles became the basis for future books.

“Wild Life in America,” his first nonfiction book, was published in 1959. A later work on Africa, “The Tree Where Man Was Born,” with photographs by Eliot Porter, was a National Book Award Finalist for nonfiction in 1973.

“Far Tortuga,” a novel of what the author called “impressionistic realism,” was published in 1975. With biologist George Schaller, Mr. Matthiessen trekked across the far reaches of Nepal in search of the near-mythic beast after which he titled his book, “The Snow Leopard.” That book won him his first National Book Award in 1979.

The inspiration for “Shadow Country” goes back to a childhood fishing trip in Florida. Out on the boat one day in the southwestern Everglades, Mr. Matthiessen’s father related a tale of an infamous sugar planter who had lived up a nearby river and been murdered by a posse of neighbors in 1910.

The lurid tale intrigued and haunted Mr. Matthiessen for years. In the 1970s, he began researching the subject, slowly becoming obsessed by it. He read old newspaper articles on the murder, unearthed books about 19th Century Florida, and tracked down relevant gravestones.

“There were plenty of myths surrounding the story but not enough facts,” he said. “I knew a novel would give me the freedom to create my own legends and characters. A 1,300-page book covering the period between the Civil War and the Great Depression was the result.”

The central figure, E.J. Watson, was rumored to have killed 55 people, including the female outlaw, Belle Starr. He was reputed to have used extreme brutality against nature and his workers in clearing the land for planting sugar. Mr. Matthiessen’s giant book explored all the lore and embellished on it.

Eventually, Mr. Matthiessen and his publisher decided a trilogy was the way to handle the massive amount of material, and between 1990 and 1999 three separate books were published: “Killing Mister Watson,” “Lost Man’s River,” and “Bone by Bone.” Though the books were well-received, Mr. Matthiessen was not content.

“I was never satisfied with the trilogy,” he explained. “I always felt ‘Lost Man’s River’ was a weak book, a wedge between the two stronger novels. The work felt unfinished. I wanted to go back to my original notion of one big book. In creating ‘Shadow Country,’ I completely rewrote huge sections of the three original books, strengthening the plot, chiseling away at weak passages, and reducing the total number of pages by 400. I was a fierce editor of my own writing.”

The author, who was born into an affluent Manhattan family, said that he was “a rebel as a youngster and spoke up against cruel snobbery. I became a counselor for underprivileged boys when I was 13. I was barely taller than the kids.”

Mr. Matthiessen, a Buddhist teacher, has led a life defined by reverence for nature and mankind, which is reflected in his writings. The Sagaponack, or ocean, zendo is on his property.

In the “Author’s Note” section of “Shadow Country,” Mr. Matthiessen wrote, “...it may be argued that the metaphor of the Watson legend represents our tragic history of unbridled enterprise and racism and the ongoing erosion of our human habitat as these affect the lives of those living too close to the bone ... I have always enjoyed their voices and enjoyed writing about them ...”

With one exception, the reviews of “Shadow Country” have been excellent. The critic from “The New York Review of Books” wrote: “Altogether gripping, shocking, and brilliantly told, not just as a tour de force in its stylistic range, but a great American novel.”

Mention of a review by New York Times critic Tom LeClair elicited this response from Mr. Matthiessen: “The only bad review I got was from my old hometown paper. LeClair may not have read the whole book.”

Addressing Mr. LeClair’s comparison of his work with Faulkner’s, Mr. Matthiessen said, “For one thing, we have completely different writing styles.”

Discussing fiction and nonfiction, Mr. Matthiessen said, “I prefer fiction. In fiction it is possible to explore deeper truths. One’s imagination can go anywhere. In nonfiction you are stuck with the facts. I am always surprised by fiction. My characters take on lives of their own. I invent them and then I don’t know what they will do.”

The interview over, Mr. Matthiessen turned off the studio lights one by one. Without the benefit of a flashlight, he led the way single file though the pitch black orchard to the barely discernible driveway and the visitor’s car.