[caption id="attachment_61885" align="alignnone" width="800"] Tim Murphy. Chris Gabello photo[/caption]

Tim Murphy. Chris Gabello photo[/caption]

By Michelle Trauring

In the beginning, there was only fear and confusion.

Then, there was anger—a burning rage that gave way to activism. It was a rallying call to mobilize and politicize the historically complacent gay community.

It was unprecedented.

It was an epidemic.

It was HIV/AIDS—a looming, omnipresent shadow responsible for slowly unraveling one life at a time.

From the front lines, journalist and activist Tim Murphy is watching history repeat itself. Except today’s epidemic is a new breed of disease. And in New York City, “protest has become the new brunch,” he said.

They call themselves “Rise and Resist,” an anti-Fascist, anti-Trump, anti-right wing group that meets every Tuesday to discuss a wide slate of issues. For Mr. Murphy, his primary concern and focus is health care.

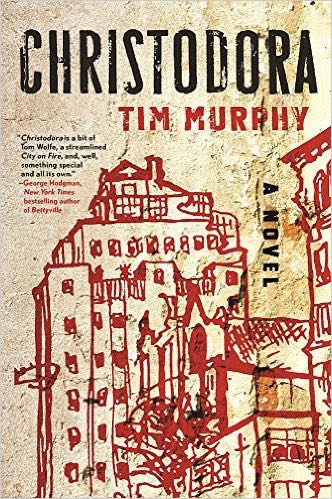

The subject, protest strategies and subsequent stresses are an echo of the past, Mr. Murphy said he has come to realize, especially since penning “Christodora.” His newest novel spans generations, telling the tale of AIDS and LGBT activism in New York City over the past three decades—the subject of his discussion on March 22 at Writers Speak Wednesdays at Stony Brook Southampton, and the inspiration behind a new mini-series currently in development.

“Even when I started writing the book back in 2009, it felt kind of antique and period, and now it feels very present and relevant to the moment,” he said during a telephone interview, recently home from a promotional tour in France, the United Kingdom and Lebanon. “I thought the book was speaking in some ways to the past, but now it’s speaking to the present. I didn’t think the activism and resistance I portrayed in the book would be such a part of our life today.”

“Even when I started writing the book back in 2009, it felt kind of antique and period, and now it feels very present and relevant to the moment,” he said during a telephone interview, recently home from a promotional tour in France, the United Kingdom and Lebanon. “I thought the book was speaking in some ways to the past, but now it’s speaking to the present. I didn’t think the activism and resistance I portrayed in the book would be such a part of our life today.”

He could have never predicted his calling as a child in small town Massachusetts. But he did strive to be a writer in New York since he can remember. It was a place where he thought he could fit, he said. A place where he could be himself.

“I grew up in North Andover and that was boring,” he said with a laugh. “It was white. It was white and Catholic and somewhat conservative. For me, as a young gay boy growing up in the 1980s, it felt very stifling and homophobic. I was the recipient of a lot of bullying.

“I think only later I realized how many actually wonderful, smart, open-minded teachers and friends I actually had, and so I have more of an appreciation now,” he continued. “At the time, I really just wanted to leave.”

In 1991, he would. And while he had missed the heyday of AIDS activism, he could still feel its aftershock throughout Manhattan, and listened to the stories of those who had lived through it.

“The ’80s were horrible. Not only was there no treatment, AIDS was a totally new disease. People didn’t even know what it was,” Mr. Murphy said. “Even when they isolated it to the HIV virus, they didn’t know how to stop it—and there was no political will to do so. It was such a homophobic time. Being gay was the punchline of a mean joke. That’s how people from President Reagan on down saw gay people. They were like, ‘What’s the problem? This is great. These are the people who we want to die anyway.’ And I’m not even joking.”

Senator Jesse Helms called for a quarantine of people who tested positive for AIDS, and referred to gay men as perverts. “Meanwhile, in cities, people were getting sick and dying left and right,” Mr. Murphy said.

Enter the grassroots organization AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT UP, which came together at a critical point—when the need for HIV/AIDS research was an a all-time high, and when anger had hit a critical mass. The group’s coordinated assault on the government proved successful, and its remnants still lingered in the air when Mr. Murphy came on the scene.

“There was still fear and there was still confusion for a lot of people, including me,” he said. “AIDS was a dark cloud hanging over the city, especially if you were gay. I wanted to understand it and to confront it and not just avoid it and pretend it wasn’t there. I was like, I’m a writer, so that’s what I did—first for Gay Men's Health Crisis, then Poz magazine. It was my way of dealing. I was learning about it and talking intimately about it. I was writing my first profiles of people living with HIV/AIDS at 23, 24. People who did not have much longer to live.”

There was Mary Fisher, the daughter of a rich Republican donor who urged for compassion for people with HIV/AIDS at the 1992 GOP convention—a very hostile, conservative setting, he said. There was the older gay man who had gone blind from complications with an eye infection and, sitting in his little studio on the Upper West Side, insisted on playing piano for Mr. Murphy.

And then there was the 7-year-old boy from Queens who instantly captured the journalist’s heart.

“I vividly remember spending an afternoon with a grandmother raising her HIV-positive Latino grandson. His mother had already died of AIDS,” Mr. Murphy said. “I spent the afternoon with them and he had a real tough white Irish grandma. She was a biker, a Hells Angel. They were so close, but he had already been very sick, and he was just so adorable. And then he died just a year or two later, and I’ve never forgotten.”

As his depth of knowledge continued to grow, so did his exposure as an HIV/AIDS reporter. Now a regular contributor to the New York Times and New York magazine, he did temporarily switch beats to focus more on arts and culture, traveled, and even published two novels—“Getting Off Clean” and “The Breeders Box”—in his late 20s.

On the surface, he led a fast-paced lifestyle. But underneath, demons lurked. And, right around this time, they did catch up.

“I had my own really dark period of depression and drug addiction and my own HIV diagnosis,” he said. “After years of having really safe sex, I became very careless. And that’s when it happened. I think at the time when I found out, I was so much in the addiction that I wasn’t able to fully emotionally process it. That came later.”

He would make his way out of his haze three years later—searching for direction, struggling with his identity. He couldn’t even walk into The Strand without wanting to vomit.

“I had abandoned fiction for years. I just, I lost my appetite for it. I went several years without writing fiction and barely reading fiction,” he said. “I was so involved in the news cycles and deadlines and breaking news. And then, at a certain point, I felt like, ‘Gee, maybe I should try that again.’ It was such a big part of my life. I felt like it was something that I lost. That’s when I started writing ‘Christodora.’”

Another three years later, he would have a finished novel that begins, revisits and ends with the namesake building. It presides over the neighborhood through its ups and downs, witnesses lives passing in and out, but never comments—like a sphinx, a god, or the eyes of T.J. Eckleburg.

It is a book about love, family and hope, about people breaking apart and coming back together, a picture of hope and resilience, he said. These themes balance out the darkness, he said.

“I felt like I really needed to write a very graphic book about AIDS, about mental illness, about drug use, about addiction, about recovery, about kind of sad and bad things. I really felt like I needed to write that book,” he said. “So I just said to myself, ‘I’m just going to write it and I will get it published one way or another, even if I have to self-publish it.’ I guess I’m pleasantly surprised; I think it’s done well.”

Last August, Paramount TV optioned “Christodora” for a limited television series helmed by writers Ira Sachs and Mauricio Zacharias. According to Mr. Murphy, they are in the preliminary stages of pitching it to various networks.

“I’ve already read their script and saw the visual treatment. They’ve retained the structure of moving back and forth in time. I would love to see what that looks like. I’m just really hopeful it gets made,” he said. “I tried to create a really vivid, textured picture of the city in the ’80s and the ’90s. I tried really hard to write a very cinematic book. I felt like I was watching the film in my head as I wrote the book, so I would love to watch the actual film.”

The AIDS-ridden New York City of the 1980s is barely recognizable today, thanks in large part to the anti-HIV medication PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis, which has helped remove a certain level of fear from young gay men.

“The effective medications came along in 1996. It was all about the luck of timing—’96 was the pivotal year, and if you could make it to ’96, chances are you would live,” he said. “I wasn’t scared I was gonna die. I was more regretful that I had let it happen—and that I’d have to be on medications for the rest of my life. In terms of when I got it, I feel very lucky. If it had happened 10 years before, I might not be here talking to you today.”

He wouldn’t be driving the conversation with “Christodora.” He wouldn’t be standing up for what he believes in, while working alongside a number of ACT UP veterans at Rise and Resist.

He wouldn't be making a difference in his corner of the world, and beyond.

Tim Murphy will read from and discuss his newest novel, “Christodora,” on Wednesday, March 22, in the Radio Lounge on the second floor of Chancellors Hall at Stony Brook Southampton., as part of the Writers Speak Wednesdays series. The reception begins at 6:30 p.m., followed by the talk at 7 p.m. Admission is free. For more information, visit stonybrook.edu/southampton.