By Joan Baum

By Joan Baum

Known as a witty, caustic cultural critic of the rich and privileged and of the famous and infamous, 70-year-old journalist, novelist, biographer, radio raconteur and long-time East Hampton resident Steven Gaines turns his attention to his 15-year-old self in “One of These Things First,” an absorbing, self-deprecating, deadpan humorous and painfully insightful memoir about coming of age and coming out. In seven short chapters that waited 10 long years to be written, Mr. Gaines compellingly dramatizes his story as a conflicted and loner Brooklyn boy who lusts in his heart after other boys, and he recreates, with keen observations and ear-perfect dialogue, the mainly Jewish working class milieu of Borough Park in the early `50s and `60s, a neighborhood of “churches and synagogues by the thousands and candy stores by the millions.” But Brooklyn then could have been Kansas, he says in conversation, there was no understanding of being gay (a word not yet in currency) and little acknowledgment of bullying. Two characters in the memoir, Arnie and Irv (“their real names”) terrorized him to the point of Mr. Gaines withdrawing from school and being home tutored.

The late 50s and early 60s was a time when many adolescents went to see William Inge’s Oscar-winning film “Splendor in the Grass” just to look at a young Warren Beatty. “I saw it 11 times in six days,” Mr. Gaines says. The movie, set in 1928 and about sexual longing, repression and suicide, came out in 1961, preceding by only a few months an event that would change Mr. Gaines’ life — his rehearsed attempt to kill himself, as he emerged from a corrugated box in a back room of his grandma Rose’s bra and girdle shop, where he would hide out among dresses: “Like a conductor about to give the orchestra a downbeat, I raised my clenched fists and then with all my might I punched through the two lower windowpanes of glass, one fist through each, one fist, two fists . . . I sawed my wrists and forearms twice back and forth across the shards that held in the frame.” Surprised that he was still alive, all he could say in the emergency room to his distraught relatives – who didn’t inquire that closely – was that he did it because he “didn’t feel well.” Earlier he had considered throwing himself under the D train, northbound to Manhattan, “which I thought was more glamorous than throwing myself under a train headed to Coney Island,” he says.

As the memoir discloses, Mr. Gaines tried to be heterosexual at the urging of a well-intentioned Payne Whitney Freudian psychiatrist, Dr. Wayne Myers whom he saw for 12 years and whom he wanted to please. The profession then, as Mr. Gaines points out in conversation, was influenced by the views of psychoanalyst Edmund Bergler who had written “Homosexuality: Disease or Way of Life (1956).” “He had lists to the effect that you’re a homosexual ‘if you’re afraid of bees,’ if you indulge in ‘injustice collecting,’ etc. Of course, the attempt at homosexuality didn’t work. A childhood image of a bare-chested, sweaty lawnmower guy kept reappearing, and relationships with women, while sometimes greatly rewarding, were never satisfying – to them as well as to him.

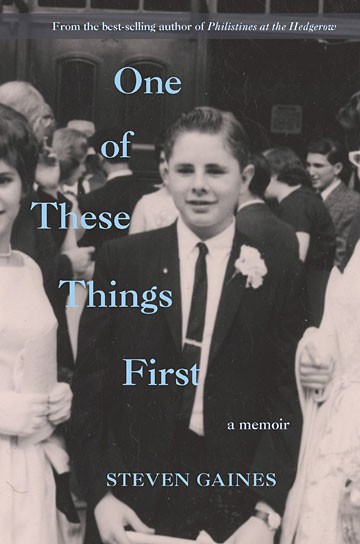

[caption id="attachment_54345" align="alignleft" width="452"] A young Steven Gaines.[/caption]

A young Steven Gaines.[/caption]

In 1972, however, when Mr. Gaines was 26, the English pop composer and lyricist Nick Drake, whom the young writer admired, overdosed at the age of 26, leaving behind music Mr. Gaines had found “beautiful and melancholy.” Among Drake’s songs was “One of These Things First,” a moving riff on the theme of what a person could have been (when Mr. Gaines was 12, identity concerns also emerged when his father changed the family name from Goldberg). Mr. Gaines had just had his first book published, a biography about the child evangelist Marjoe Gorner, whom he had met at the Manhattan nightclub and restaurant, Max’s Kansas City. The prescient encounter says a lot about the entrepreneurial Mr. Gaines. As he writes in an email: “I had zero writing credits; never thought seriously about writing a book before; I existed day to day moving furniture at an auction gallery.” But the movie made about Margoe, not relying on Mr. Gaines’s book, won an Oscar and the young writer found himself with a hot topic and opportunities. He decided to come out, but, he said, “that didn’t mean I was a happy camper.”

“Nostalgia is dangerous,” Mr. Gaines has said, admitting that he feels a bit “vulnerable” now that “One Of These Things First” is published. The memoir is not a confessional trip down memory lane, but a lyrical, dispassionate, humane story with a rich cast of characters that includes parents and grandparents, peers and strangers, shop keepers and psychiatrists, and movie stars whose cinematic lives keep popping up amusingly in the narrative as influences. Stars also dominate the center of the memoir, which is young Mr. Gaines’s recollection of his stay at the “fabled and fashionable” Payne Whitney Psychiatric Clinic of New York Hospital, “the Ivy League of psychiatric hospitals.” Scheduled to go a facility in Queens after his suicide attempt, he audaciously insisted on Payne Whitney, after learning that Marilyn Monroe, who had had a nervous breakdown, signed herself in there. His first night was sobering: “I was hoping to find a wise, middle-aged doctor, like Lee J. Cobb in “The Three Faces of Eve,” who guides Joanne Woodward back from multiple personalities and helps her reduce all the people inside her into one healthy person, a role for which she won the Academy Award for best Actress in 1957.”

Because of the timely subject matter but also because of its informal prose style, the memoir could well attract a young adult readership. Mr. Gaines captures the coordinating-conjunction voice of the pre-teen set – “and. . . and . . .and” -- but he also demonstrates the style of a mature writer who knows how to delay for ironic effect: Of a former editor he met at Payne Whitney, he says “She had gray ringlets across her forehead like a flapper, and she was wearing a flannel bathrobe and men’s pajamas. She owned a small savings and loan in Vermont and shoplifted at Bergdorf Goodman.”

A back cover blurb by actor and playwright James Lescene, whose sold-out July performance at Bay Street Theater in “The Absolute Brightness of Leonard Pelkey” -- about a murdered gay teen -- calls Mr. Gaines’ memoir “a heart-rending testament of surviving the oppression and the denial of self.” And beautifully written.

Steven Gaines will speak about his memoir at Fridays at Five at The Hampton Library, 2478 Main Street Bridgehampton, on August 12 at 5 p.m. For reservations, call (631) 537-0015; On Saturday, August 13, he will join dozens of authors at the East Hampton Library’s famed Author’s Night: for tickets, visit authorsnight.org. Mr. Gaines will also read at Southampton Books on Sunday, August 21 at 5:30; and at Bookhampton in East Hampton on Thursday, August 18 at 7 p.m.