For all the Northern California biographical and literary associations the name “John Steinbeck” evokes — because it was his birthplace, his longtime residence and the setting for so much of his fiction — Steinbeck was also a celebrity in Sag Harbor where he made his home in 1955 with his third wife Elaine, after renting for a couple of years. He died in 1968, six years after winning the Nobel Prize for Literature, having become a familiar presence in the village, the founder and co-chair of the Old Whalers Festival, now known as HarborFest.

“A handsome town,” as he once described Sag Harbor, he became the village’s famous recluse, opting, as he had done all his life, for solitude to write when he wasn’t spending time in a bar or on walking around the waterfront. He set his last novel “The Winter of Our Discontent” (1961) in Sag Harbor, and in 1998 Bay Street Theatre named its stage after Elaine (d. 2003), an honor she acknowledged with more grace than her husband who, when asked once if he had deserved the Nobel is reported to have said, “Frankly, no.” John Steinbeck was not an easy man to know, an intense person given to degrees of depression and temper.

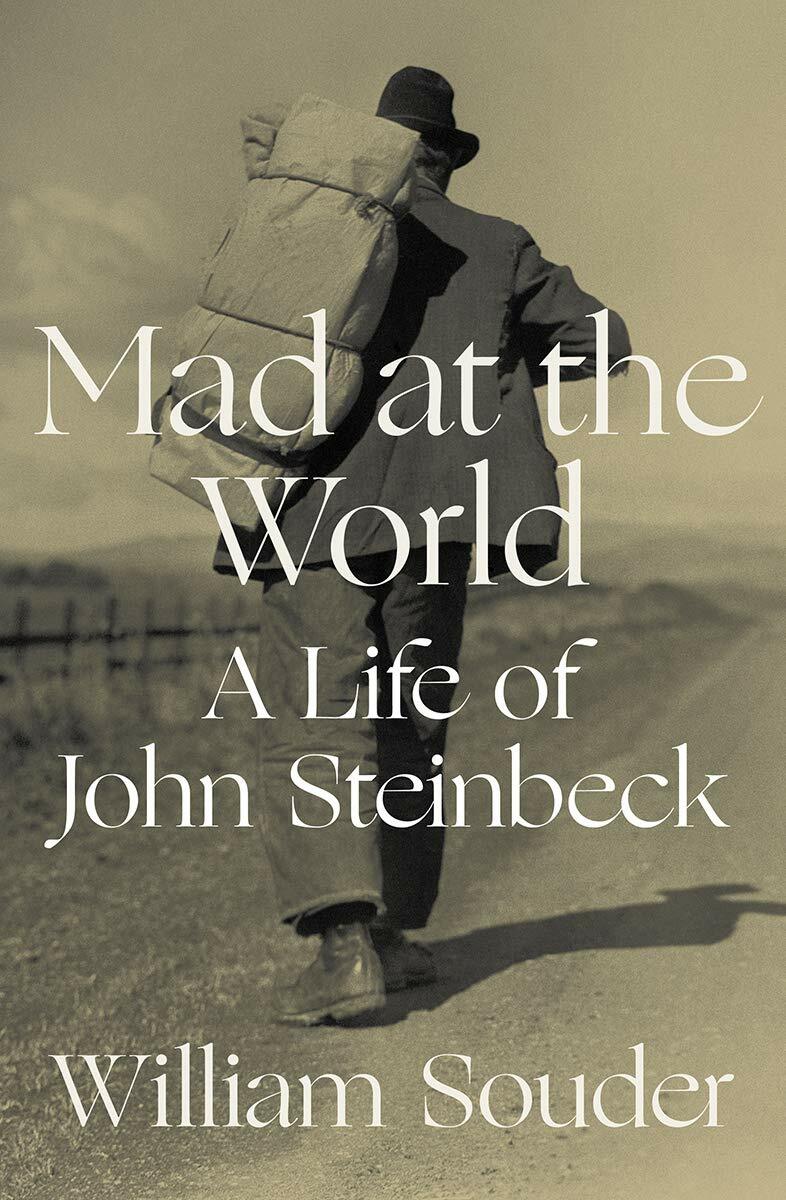

These facts and others about this award-winning mid-century American voice of the fated, lonely and dispossessed, the author of over 30 books and journalism, are well known, so a question arises — a key question — why another look? What motivated William Souder to pen “Mad at the World: A Life of John Steinbeck,” a comprehensive chronological narrative accompanied by black and white photos? Is there new material about Steinbeck’s life or writings? Corrections to accepted standard studies that need to be redressed? Something in the contemporary air that reflects or validates Steinbeck subject matter or themes? Souder doesn’t say, though he provides an extensive list of primary and secondary sources, including numerous works about mid-century America and the world. The book jacket for “Mad at the World” does say that Souder’s is the first full-length biography of Steinbeck “to appear in a quarter of a century,” but is this fact sufficient rationale for a new extensive revisiting?

Souder is upfront about his admiration for his flawed literary subject and fair in noting numerous times “multiple” versions of, or takes on, various stories about Steinbeck’s personal life and career trajectory, but does his sympathetic look change the overall assessment of the man or the writer? (Steinbeck was no Hemingway or Saul Bellow, to note a couple of fellow American laureates.) It’s even arguable that Souder’s title is not realized — how did “anger” (as distinct from passion or compassion) inform his choice of subject matter, reputation, relationships with women and friends? At many junctures in his narrative Souder relies on words such as “perhaps” or “maybe” and lets inconclusiveness ride.

The author, whose previous works celebrate Rachel Carson and John James Audubon (this last a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize), writes well, especially when he is describing landscape. Indeed, there is something rhythmically Steinbeck-like about Souder’s own prose, evident from the opening paragraph of “Mad at the World.”

“In the California winter, after the sun is down and the land has gone dark, the cool air slips down the mountainsides that flank the great Central Valley, settling over the fields and tules.”

“Mad at the World” is a carefully researched, appreciative biography that avoids partisan or academic lit-crit theories. It would connect the man and the works with the times, but the juxtapositions at times seem more arbitrary than integrated — chunks of mini-history (extended accounts of strikes, wars, contemporaries) that precede or follow summaries of various Steinbeck works. References and allusions to interviews and correspondence, identified only in endnotes, might have been more effective if flagged in the narrative itself.

Yes, John Steinbeck was doggedly determined about writing, diffident about success and often depressed. And talented. All known. It’s unfortunate, therefore, that Souder’s portrait doesn’t seem to shine new light on the man who, as Souder says, “blended fact and fiction in what he wrote and in what he said about himself.” If Steinbeck remains a man who was hard to know, he also remains here a man hard to place in the pantheon of great American fiction.

Nonetheless, “Mad at the World” is about an important literary figure who spent much of his later life on the East End and became an iconic figure. It may well be that aside from select short stories, Steinbeck is no longer read much, and so for new generations and those who know about him only from movies or dramas, Souder’s book has special value.