On Thursday, June 24, at 12:30 p.m., those curious about whales and art will be able to Zoom into a talk sponsored by Canio’s Books as a kind of heads-up to its biennial Moby Dick Marathon, to run this fall over HarborFest weekend in Sag Harbor starting September 10.

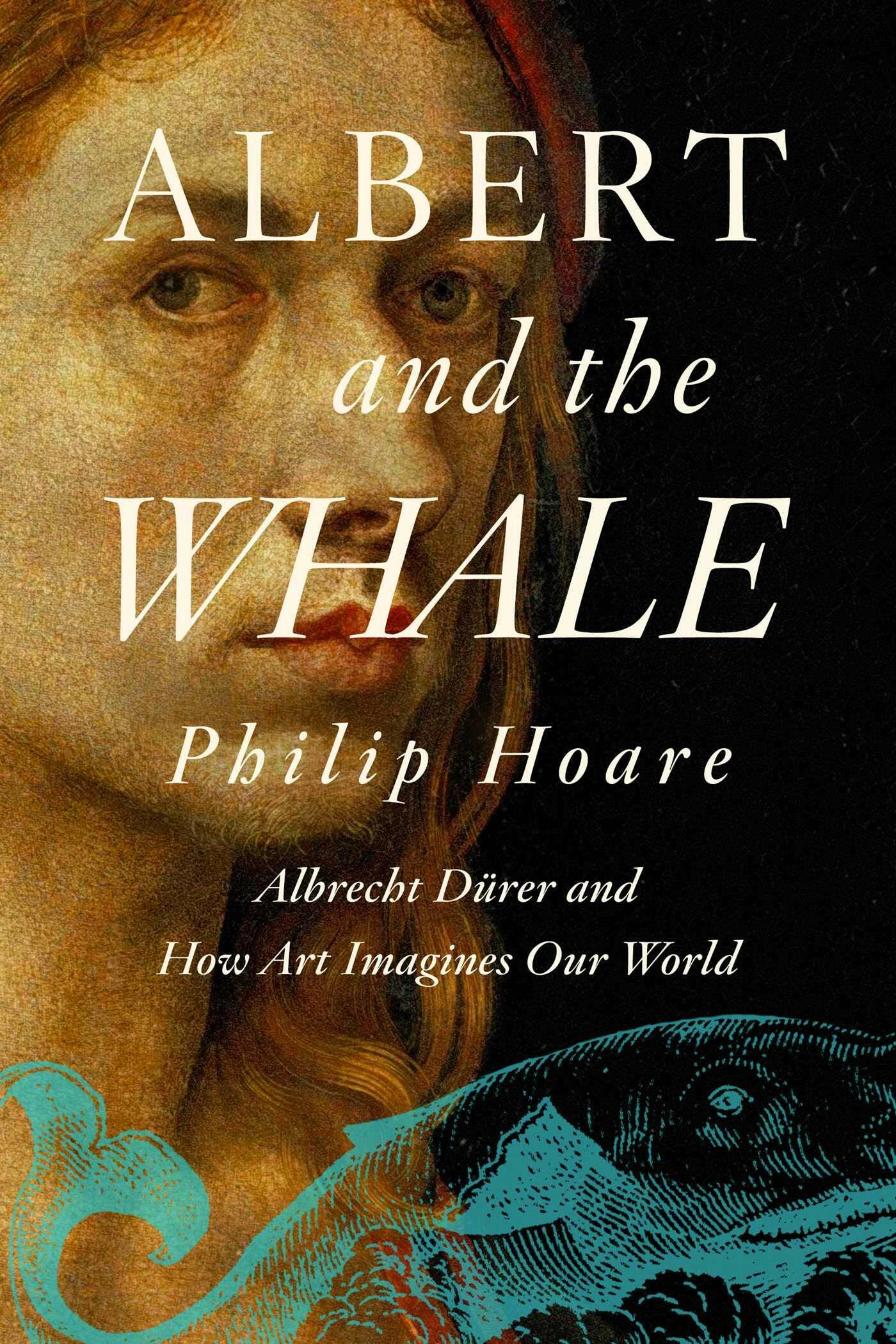

The speaker, 63-year-old prize-winning author Philip Hoare, who inaugurated the Moby Dick Big Read project and exhibition at The University of Plymouth, England, in 2011, acknowledges he has a “whale obsession.” His resumé includes several works of nonfiction and a BBC film, “The Hunt for Moby Dick.” Readers of his new book, “Albert and the Whale: Albrecht Dürer and How Art Imagines Our World,” will be treated to an eloquent, erudite and insightful collection of observations on the visual arts, cultural history, literature, philosophy, whaling, and so much more, all accompanied by images of Dürer’s etchings, woodcuts, paintings and drawings, with special attention to “Melencolia I,” the “most analysed object in the history of art.” All were wrought during an age resembling our own plague, war-ravaged, famine-ridden time.

Five hundred years ago — a critical moment in the history of art, the beginning of the Renaissance — “Dürer changed the way we saw the world,” Hoare says.

Indeed, viewers of some of the artist’s works might believe they are looking at surrealism.

As for filling a canvas, Dürer outdoes Bruegel, both in the amount and bizarre nature of real-fantastic details. His self-portraits — “the shocking modernity of his gaze” [that “stare” those odd-positioned eyes] — invite speculation and wonder. His animals (that rhinoceros, that walrus!) the Biblical scenes, the “serious portraits of people of colour [the first] in western art, drawn with subtlety and sensitivity,” his diary entries — Hoare offers it all up for analysis and admiration.

As for whales, which Dürer came so close to seeing one freezing winter in Zeeland, before the ship on which he was traveling was wrecked, he desperately wanted to capture them in art. They got away, though only in real life. They became his Grail. Had Dürer ever seen one, “his art would have preempted Melville’s mutterings,” Hoare writes. Dürer understood the whale, as did Melville and all those who followed in their wake. They saw the whale in their mind’s eye — a magnificent, eternal creature, a harbinger of death for those who would kill him. And did. And still do. An inspiration for those who would create.

So, what is the relationship between Dürer and whales, especially given the fact that the artist never saw one? And what are the links between Dürer (1471-1528) and the book’s other main subjects — Melville (b. 1819), Blake (b.1757), Goethe (b. 1749), the literary Nobelist, Thomas Mann (b.1875), the great German writer Georg Sebald (b. 1944), the American poet Marianne Moore (b. 1887), the Anglo-American poet W.H. Auden (b. 1907), David Bowie (b.1947) and Hoare himself? He connects them and with history, philosophy, the ocean, the land.

Other personalities wade in on diverse currents, many with bisexual proclivities — Oscar Wilde, the English and German Romantic poets, friends, lovers, family, colleagues, acquaintances, strangers, dogs.

He revisits places he’s lived, “having swum through libraries and sailed through oceans,” museums and special collections, brought to him by “sub sub-librarians” shuffling out of arches in dust (the quotation comes from the opening pages of “Moby Dick,” before the narrative).

Though “Albert and the Whale” blends scenes, memoir and history, and present events are pressed out of the past (the absence of quotation marks enforces the blurring), it’s not necessary to recognize all the sources or closely follow Hoare’s leaping imagination in order to appreciate what he’s doing and how. Sentences follow in apparent discordant sequence, universalizing time and making places ubiquitous — like Moby Dick.

There is Dürer’s ravaged, catastrophic 16th century; here, the bomb and prospect of nuclear war. Then was the “outrage of [Dürer’s] genius”; now, Hoare’s (and Dürer’s and Melville’s) implicit cry to yield to The Whale. Between 1914 and 1917, Hoare writes, thousands upon thousands of whales died to produce nitroglycerine for British bombs and oil to stop soldiers’ feet rotting.” World War II only upped the number of whales killed. Nature, Spirit, Art, Humanity. Need Ishmael be the only survivor of our brave and brutal new world?

“Albert and the Whale” (more Albrecht than leviathan) is at heart personal testimony to Hoare’s extensive reading and impassioned love of all things Sea — he swims almost every day, no matter where he is in the world. He knows its surfaces, depths, changes, creatures real and imaginary, history, dangers, beauties. As much as he invokes myth and literature (in several languages) to describe its lure, he manages to create his own memorable phrasing and metaphors and Coleridgean “streamy nature of association.” A fine poet in prose.

Philip Hoare’s lunchtime Zoom talk is Thursday, June 24, at 12:30 p.m. To register, visit canios.wordpress.com.