One thinks of the coyote as a resident of the Western plains. The truth is that coyotes have been migrating eastward over the last 25 years. There have been coyote sightings in Queens and even one in Water Mill.

Aquidneck Island, in Rhode Island, which is the home of Newport, Middletown and Portsmouth, is overrun with them. They disrupt the ecological balance and pose a threat to the community, as well as a danger to household pets. As the coyotes lose their fear of humans, residents become afraid for their children.

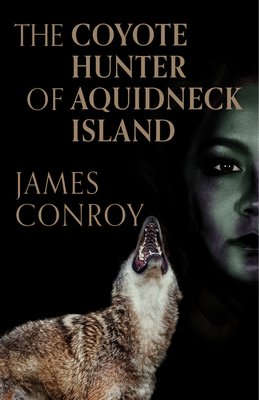

James Conroy has turned this very real problem into a gem of a novel, “The Coyote Hunter of Aquidneck Island” (Permanent Press, 344 pp. $29.95). Mr. Conroy is the author of several thrillers. This is a departure for him.

The town board of Middletown and Mayor Mary Boyd (both fictional), have decided to hire a professional hunter to cull the coyote population in a humane way. The decision is unpopular with both animal rights activists and with local sportsmen, who want to take a crack at hunting the coyotes. The hunter they hire is a former army sniper and was recommended by the town’s game warden. The hunter wants a place to stay to avoid unnecessary and unwanted attention. Micah La Vek, a retired civil servant and writer, has a space behind his house for the hunter’s trailer. The always elegantly coiffed and manicured mayor’s chief of staff, Laurie Catlett, an old flame of Micah, persuades him to offer the space behind his house. Micah is of two minds about the culling process and is not comfortable with it. Nevertheless, he agrees. When the hunter arrives, Micah is surprised to find that the hunter is a woman and a Native American, Kodi Red Moon. Micah is hospitable and invites her for dinner, yet they keep a decorous space between them.

Kodi goes about her business methodically and humanely, killing with a surgical precision, then turning the carcasses over to the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management. Micah sees the first two dead coyotes in Kodu’s truck. “To him, they hardly seemed dead, more like asleep. One with its head on its front paws, the other curled with its snout tucked between forelegs. All eyes closed, no tongues hanging out, and no sign of blood. It seemed so natural, or arranged to be so.” The point is that the killing is humane, and so quick that pain is minimal. Gone before they knew what happened, one bullet behind the ear.

When a neighbor complains about the presence of Codi’s trailer, Micah offers her his spare bedroom and the police chief offers to keep the trailer in the police impound area without charge.

Kodi has given an Indian name to Laurie Catlett, who is technically her boss. She calls her “Wawotam Kokak,” which means “Cunning Crow,” and to which there is a slang equivalent, “Wawokak.”

“I like it,” said Micah, “and very insightful on your part. It fits at every level.

“Got an Indian name for me? ...”

“Yes,” she hesitated, “but it was kind of before we got to know each other.”

“Let’s have it.”

“‘Pumsha Pokasu,’” shortened to ‘Pumpok.’”

Micah raised his eyebrows for the translation.

“‘Walks Tilted.’”

“Helluva lot better than Cunning Crow.”

Micah has a rare disease of the cerebellum that affected his walking and his balance. He walks with a cane. Hence, “tilted.” These names are a comic leitmotif throughout the book, appearing like raisins in a soda bread.

But politics comes to a boil when one of the local sportsmen kills a coyote and leaves its mutilated corpse in the middle of Main Street. Kodi has always kept a low profile, never drawing attention to herself or her work, but an investigative reporter is doggedly turning over every rock to find her. The mayor herself always considered Kodi to be a compromise between the environmentalists and the sportsmen who would kill for the sake of killing. But she soon realizes that compromise isn’t an option and her political life is on the line.

Laurie Catlett has her own agenda. She is jealous of Kodi and politically ambitious. Not a good combination, it turns out.

The novel has an interesting subplot, almost a parallel plot, in Micah’s research into a figure whose journals, which date to before the Civil War, he is editing for publication.

Central to the narrative is the touching friendship and developing romance between Micah and Kodi, which is tender and complicated, given the difference in age and background, but leavened with humor. They are complex characters and fully realized. Each has something to learn from the other.

Even the minor characters come alive with a stroke of the authorial pen. The prose is “clear as a pane of glass,” George Orwell’s recipe for English prose. The pace is unrushed but never lags.

Mr. Conroy explores so many of the facets of the human condition: humankind’s relation to nature, love, death, illness, ambition, politics, religion, compassion and our ties to the past. And it all seems effortless.

The Permanent Press is submitting “The Coyote Hunter of Aquidneck Island” for consideration for the National Book Award. It is that good.