“Knowledge Is Power” — Francis Bacon

The John Jermain Library in Sag Harbor has a small, but well-rounded selection of books about the environment. They share the shelf with the true crime category.

Naturally. Why wouldn’t books about all that we’re doing to the planet be right next to a book about Charles Manson? Climate change is after all, a really scary subject.

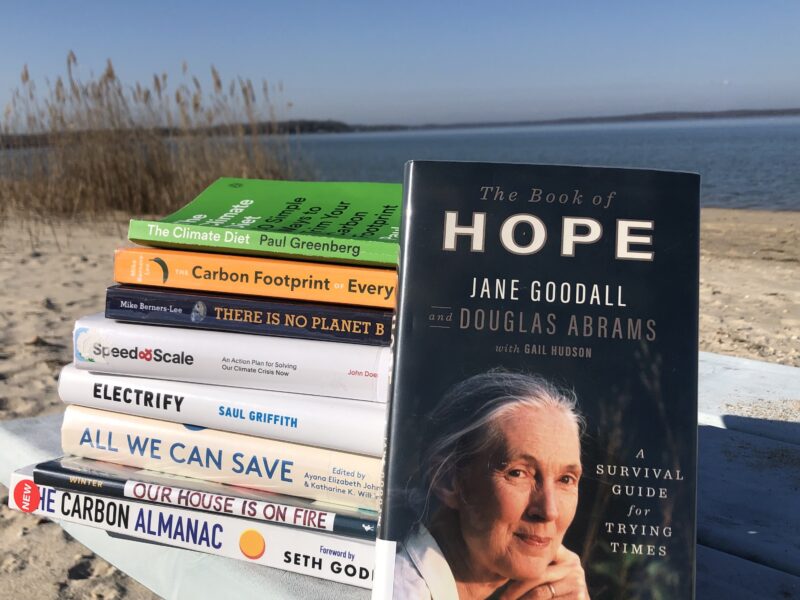

Out of the plethora of books recently written on the subject, I tracked down seven that inspire hope. Not the namby-pamby, sugar-coating-the-crisis, kind of hope. Or the false hope that God or science or interplanetary colonization will save us. But real hope. The kind that Jane Goodall calls, “rational hope” and describes as a practice rather than just an emotion.

There are other good books out there, but I culled this list down to seven well researched, solution-based books. And ones that, of course, are a great read.

“The Carbon Almanac: It’s Not Too Late”:

This book of facts (or what I’d call fun facts) has got it all. There are chapters about edible insects, how roundabouts reduce carbon emissions and the climate cost of a leaf blower. It discusses all sorts of climate change effects — from potholes and Lyme disease to higher taxes and fewer ski days.

There’s an incriminating 1982 letter from Exxon. And a poem by Maya Angelou.

It models what a day in the life of a net zero emissions would look like. And in the myth section, Myth #7 — “climate change does not affect me personally,” definitely applied to me.

Toward the end, it calls out 10 publishers who promote climate change denial, as well as top donors in climate philanthropy, and the most influential artwork about the environment.

If a book about climate change could be entertaining, this would be it.

“The Book of Hope: The Survival Guide for Trying Times”:

Jane Goodall is the personification of hope. She describes her own “improbable journey” of becoming the foremost expert on chimpanzees as possible only because she never lost hope. Month after month, the chimpanzees she was researching in the jungles of Tanzania would see her and run away, making her fear the futility of her project and disappointing her new boss, Dr. Louis Leakey.

This book is written as a deeply personal conversation between Goodall and author Douglas Abrams, a self-proclaimed New York cynic who was as skeptical about Goodall’s vision of hope as I was.

Despite his skepticism, we are won over by Goodall’s powerful and convincing message: Hope is the stubborn determination to succeed, despite the odds.

Goodall lays out her four concrete reasons for hope: The Amazing Human Intellect, The Resilience of Nature, The Power of Young People, and The Indomitable Human Spirit.

Spoiler alert: the chimpanzees stopped running away from her.

“The Carbon Footprint of Everything”:

“Everything” here comprises everyday activities and objects that are categorized by how much carbon they emit.

Here are some of my favorites:

Less than 10 grams of carbon category: A text message, drying your hands, a pint of water.

10-100 grams: Ironing a shirt, a Zoom call, and my favorite bit of randomness — walking through a door.

100-500 grams category: A banana, an hour watching TV, a shower.

1.1 to 2.2 pounds: A latte, spending $1, a paperback.

22-220 pounds: A pair of shoes, a night at a hotel.

220 pounds to one ton: A funeral, a pet, a mortgage.

10-100 tons: Space tourism, a car crash, having a child.

Billions of tons: Wildfires, a war, the world’s annual emission.

This book inspires you to pick your battles over what to do (or not do). I pledge to give up ironing a shirt and space tourism, but definitely not my lattes.

“Electrify: An Optimist’s Playbook for Our Clean Energy Future”:

Engineer and inventor Saul Griffith has a simple plan. Electrify everything.

This technological optimist sees the climate crisis as an opportunity for change. His blueprint doesn’t rely on big, not-yet-invented innovations. He posits that we already have the most important technical solution in front of us today.

“America can reduce its energy use by more than half just by introducing electrification,” says Griffith. “When energy is cheap, everything becomes cheaper.”

In the chapter, “A Mortgage Is a Time Machine,” he argues that if the government were to offer “climate loans” at a low interest rate, people could afford the upfront cost of solar panels and electric heat pumps to start saving money now.

He recommends not to sweat the small stuff. Driving an EV and installing solar panels are one-time decisions that have much more impact than the small decisions we make every day.

Griffith makes a powerful argument to end the massive subsidies and tax breaks that support fossil fuel companies.

“Our House Is on Fire: Greta Thunberg’s Call To Save the Planet”:

The story of Greta Thunburg is proof that the biggest changes can come from the smallest people.

In Jeanette Winter’s colorful book, written for the six-plus set, we follow the journey of a lone protester on the snowy streets of Stockholm as she sparks a worldwide climate movement. With her faithful dog, Roxy, by her side, we join Greta as she looks at images of ice melting into the sea, coral reefs that were “pale as ghosts,” and a smoldering sun scorching the earth, leaving it “bone-dry.”

“What can I do?” Thunburg wonders. She starts by skipping school every Friday to sit outside of the Swedish Parliament building with a sign that reads, “School Strike for Climate.” Little by little, students join her protest and eventually march in 43 different countries.

This climate change super hero is invited to the World Economic Forum in Davos, where she tells the adults, “I want you to act as if the house is on fire. Because it is!”

“Speed and Scale: An Action Plan for Solving Our Climate Crisis Now”:

Taking a business person’s approach to solving the climate crisis, legendary technology investor John Doerr uses the powerful tool OKR to measure solutions according to how much CO2 they emit, how much they will cost, and how long it will take to reduce emissions.

Doerr says, “In order to decarbonize our economy, we need to scale up the innovations we have and invest the ones we still need.”

Some of these solutions can be done at home, especially if your home is the White House. Others can be done at work, especially if you’re a captain of industry.

He interviews an impressive constellation of thinkers: Laurene Powell Jobs, Bill Gates, Christiana Figueres, Al Gore, John Kerry, Jeff Bezos and investment manager David Blood who made sustainable investing profitable. He explores Mary Barra’s plan to make GM’s cars and trucks all electric by 2035, and includes Larry Fink of BlackRock investments who tells him, “A climate aware portfolio is no longer a choice. It’s an imperative.”

“The Ministry for the Future”:

This is one of the best reads in a growing new genre of fiction known as “cli-fi.”

Despite this inherently dystopian category, writer Kim Stanley Robinson offers up an optimistic portrait of humanity’s ability to cooperate in the face of disaster.

The plot follows Mary Murphy, the head of the titular Ministry for the Future, whose mission is to act as an advocate for future generations as if their rights are as valid as ours. Crazy, right? In a parallel plot, we follow the plight of American aid worker Frank May, after being the sole survivor of an extreme heat wave in India.

This near future novel explores climate change, existing technologies, politics, and the behaviors that drive these forces. This page turner straddles desperation and hopefulness elegantly.

More Posts from Jenny Noble

More Posts from Jenny Noble