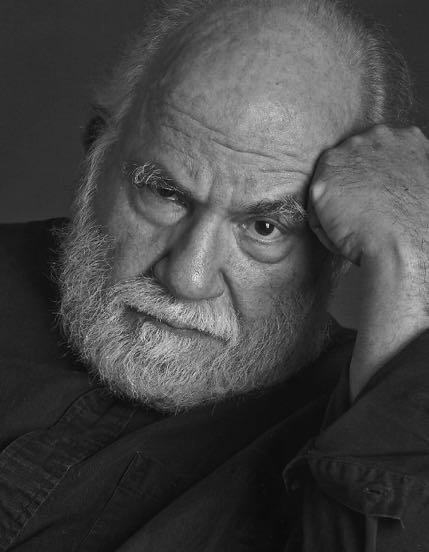

[caption id="attachment_59373" align="alignright" width="467"] Michael Edelson and his late Irish Wolfhound, Lordy.[/caption]

Michael Edelson and his late Irish Wolfhound, Lordy.[/caption]

By Michelle Trauring

On the morning of Sunday, November 15, 1959, the Clutter family did not show up for church. There were no pots on the stove, there were no dishes in the sink, there was no movement in the house.

The doorbell rang and rang, unanswered. Desperate knocks fell on deaf ears. A purse had been abandoned on the floor, half opened.

Its owner, 16-year-old Nancy Clutter, loved to bake and ride horses on the family’s Kansas farm. Her favorite was a mare named Babe. That morning, Nancy’s bedroom walls were found splattered with blood from the single gunshot to her head.

Her mother, Bonnie Mae, and her 15-year-old brother, Kenyon, suffered similar fates. It was the family’s patriarch, Herbert—a composed, quietly wealthy man—who endured torture from killers Richard Hickock and Perry Smith. They taped his mouth shut, slit his throat and shot him in the head, all for a measly $50, a pair of binoculars and a transistor radio when the farmer told them the safe they sought did not exist.

It was not a bluff. No safe was ever found on the family farm.

Three days later, close to 1,000 people paid their final respects to the Clutter family, lining the streets near the Garden City Methodist Church. This was their worst nightmare. It was every small town’s worst nightmare.

And it captured the attention of a nation, including that of a young journalist named Michael Edelman, who was working as a photographer in New York.

“It was a huge story. Unlike ever before, that following night, everyone there locked their doors,” according to Mr. Edelson, who will discuss the case and the films that followed on Sunday at the John Jermain Memorial Library in Sag Harbor. “I now live in Greenport. When I first moved here, we didn’t lock our doors. We do now. But these murders were the beginning of a shift in our lifestyle. It did change. And I was attune to this because I knew what small-town news was like, certainly.

His experience at The Canonsburg Daily Notes, a daily newspaper in western Pennsylvania, gave Mr. Edelson all the context he needed to understand the Garden City tragedy, he said, not to mention the record as youngest editor of a daily newspaper in the history of American journalism.

He would switch career paths and become a film and humanities professor at Stony Brook University for a quarter century, where he created and directed the photography program while teaching courses in studio art, art history, humanities and film studies. He was a ham, he said, constantly moving as he lectured, instead of glued behind a podium like so many of his colleagues.

Retirement has been kind to him, he said—he and his wife, Ingrid, live in a circa-1832 home on the North Fork with their two cats—but he was missing his former life. The idea came to him to give a lecture on Alfred Hitchcock at the Greenport Library, which snowballed into “Citizen Kane,” “Singin’ in the Rain,” “To Kill a Mockingbird,” and so on.

“I just love teaching. As I always said, ‘I love the kids, I hate the administration,’ because they were such twits,” he laughed. “Frankly, when I was teaching, there really wasn’t a mechanism to give the level of lectures I do now back then. I simply sit at my desk, I find the films, I find the stills, I find the information and there I am, sipping an Irish whiskey. Back in those days, I was using videotape. Now you can do this, I couldn’t before. And it’s such a delight because I’m almost 80—I’ve lived through so much!”

He remembers the peaks and valleys of public interest surrounding the Clutter family murders. And he recalls when, seven years later, Truman Capote released his nonfiction novel “In Cold Blood”—which was almost cut like a film, complete with flashbacks, despite its journalistic bones.

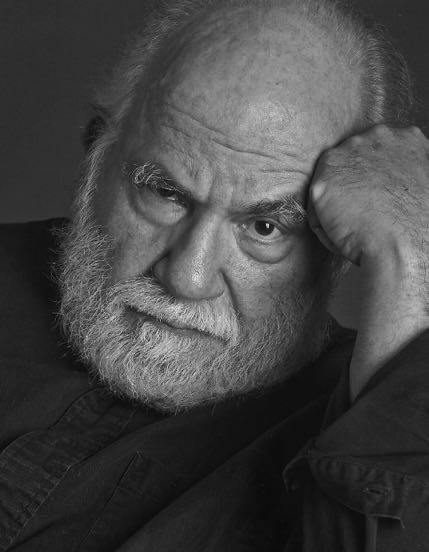

[caption id="attachment_59366" align="alignleft" width="429"] Michael Edelson.[/caption]

Michael Edelson.[/caption]

“There are problems with the book,” Mr. Edelson said. “Besides Capote saying, ‘I’ve invented a new genre’—which immediately drove up the hackles of half the literary world—there was a question as to the veracity of the facts. And keep in mind that Capote never used a notepad or a tape machine. And he claimed that he had—and he said he was tested—94 percent accuracy. So he left himself open on two scores. But it’s still a good read. And he would never write another book after ‘In Cold Blood.’ It made him a very rich man.”

Capote would go on to trust Richard Brooks with the adaptation and direction of the novel’s eponymous film, which set the bar for the three additional films and miniseries that would follow—particularly 2005’s “Capote,” starring the late Philip Seymour Hoffman.

“Hoffman’s performance is Capote. It is extraordinarily breathtaking,” Mr. Edelson said. “When I was reviewing the film and going over the scenes and back and forth, I realized what a loss his death was. I just can’t imagine what a professional life he would have had if he had stayed alive.”

In some ways, the two were kindred spirits, with misconceptions surrounding both their deaths and key moments in their lives—such as Capote’s interest in the Clutter family case. In actuality, he couldn’t have cared less, at least not at first.

“Slim Keith, one of Capote’s ‘swans,’ is quoted as saying that The New Yorker offered him two assignments. One was to go to Kansas and the other was to follow the women who have keys to apartments, come clean and go and are never seen, these invisible people,” Mr. Edelson reported. “Slim is quoted as saying, ‘Take the easy job and go to Kansas.’

“Both films use the story of him seeing the article in the Times. It’s simply not accurate,” he continued. “But it’s good fiction.”

In his research, Mr. Edelson found countless Easter eggs in the films, as well as surprising local trivia that he will share during the lecture. Capote did live in Sagaponack, after all, Mr. Edelson pointed out, though he never met the larger-than-life character.

The mythos surrounding Capote, as well as the fascination with the murders themselves, could be attributed to a never-ending interest in the case, he said. It is a story that is relatable to anyone who lives in a small town—whether it’s in the Midwest, deep South or even the East End itself.

“Certainly, the murder is horrible. Certainly, the killers are intriguing. And then you have Capote, who was a very disturbed person traumatized by his early childhood,” Mr. Edelson said. “I never taught ‘In Cold Blood,’ but if I were still at Stony Brook, I would certainly teach it. It’s an extraordinary film. And when you look at that film and Hoffman’s ‘Capote,’ it’s like you have these two bookends that contain the incredible horror and truth behind the murders. The Brooks film is 50 years old, and it is as contemporary as the day it was released.”

Michael Edelson will discuss “In Cold Blood” on Sunday, January 22, from 2 to 3:30 p.m. at the John Jermain Memorial Library in Sag Harbor. Admission is free. For more information, call (631) 725-0049, or visit johnjermain.org.