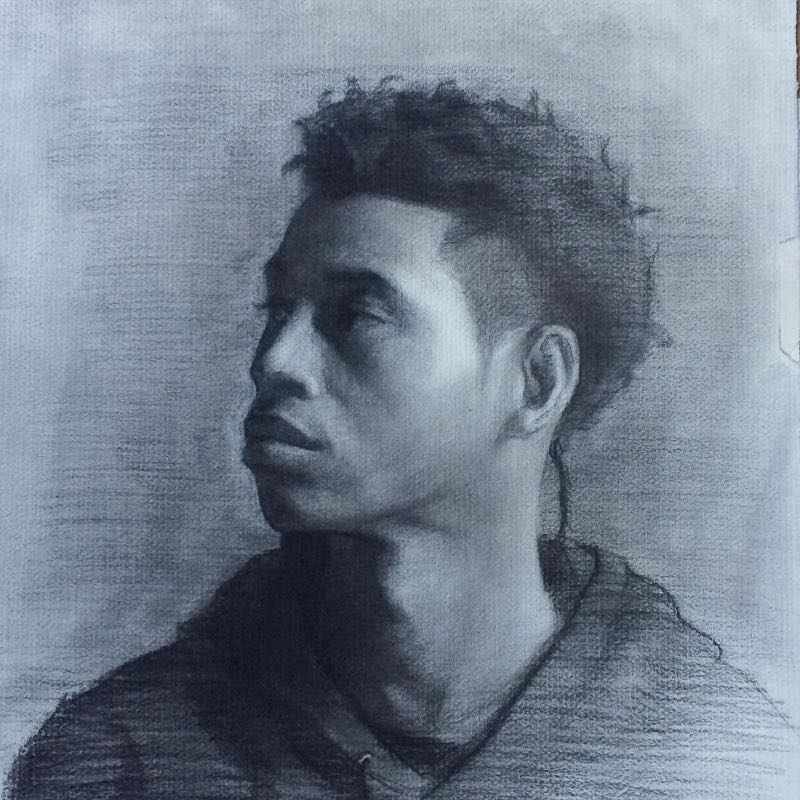

[caption id="attachment_62909" align="alignnone" width="800"] George Morton at work.[/caption]

George Morton at work.[/caption]

By Michelle Trauring

It was his portraits that caught Laura Grenning's eye.

It was his back story that kept her attention—one of the most compelling she said she's ever heard.

When she met him several years ago, she knew his name wasn't one she'd soon forget. She knew it would grace the walls of her Grenning Gallery in Sag Harbor someday, his name on everyone's lips.

"George Morton."

She was right.

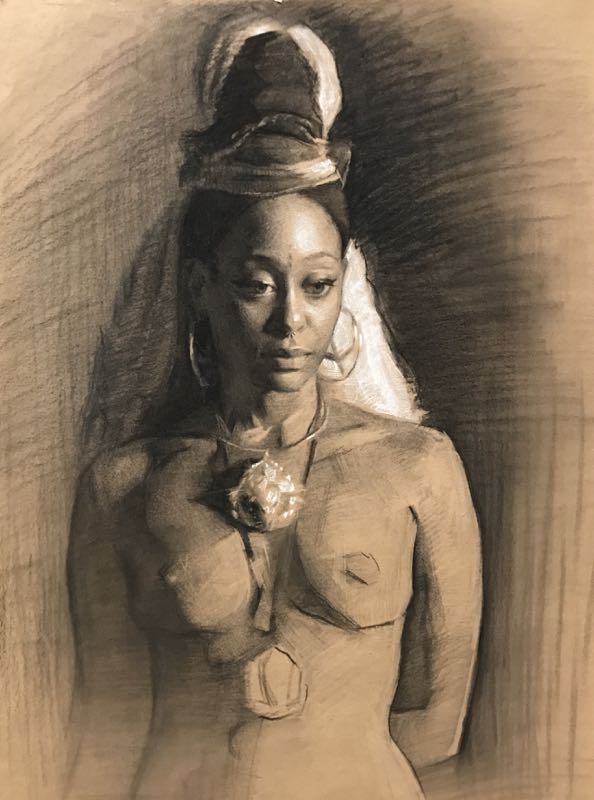

But there is more to Mr. Morton than his sheer, mostly raw talent. Take one look at his dramatically lifelike, poignant pieces, and it's there — his past, one set against the drug war of the 1990s in Kansas City, one that landed him an 11-year prison sentence.

One that nearly destroyed him.

"George Morton is a wonderful example of someone who has successfully faced very difficult life situations, some due to bad luck and some due to bad choices," Ms. Grenning said. "He was able to dig deep to find a power greater than himself."

That power is in his art. But what is now his passion once started as an escape.

Mr. Morton's first artistic memory dates back to around age 8, drawing cartoon characters with pencil in elementary school. Not long after, he began experimenting with portraits privately, already honing in on the human element and its myriad of emotions — precisely what attracts him to portraiture today.

Those moments to himself were few and far between, and the majority of his earliest memories are not artistic at all.

Those moments to himself were few and far between, and the majority of his earliest memories are not artistic at all.

Instead, they are of pure chaos.

Born to a 15-year-old mother, he was the eldest of her 11 children — all of them a year apart, living in a drug-infested household, just trying to get by.

"With my mother, we pretty much grew up together. We were basically co-parenting," he said. "So, you can imagine, I've always had the feeling my mother is just a little girl, but even more so back then. She had us back to back. Just babies having babies."

His talent never nurtured, a young Mr. Morton kept his art a secret, and focused on raising a family he didn't ask for, and living a life he didn't choose — inside a drug house, with high-level paraphernalia everywhere he turned.

It was pure survival, he said. This was his normal, and he rarely thought twice about it.

"I had some very dark experiences, actually, but beautiful, you know? Struggle, you know? A lot of struggle, a lot of difficulty," he said. "But I believe there is beauty in the struggle. I've learned over time.

"And, so, there's a lot of experiences that come with living in the midst of a drug war in your community — everything that we've come to associate with struggle, pretty much," he continued. "All the odds are against you, people are dying around you, having to fend for yourself. No real childhood. I don't regret a single day of it. I believe we just take lemons and make lemonade out of them. I may not have had the best hand, but I play it like it's the best."

Immersed in this world, his mentality and one defining moment led him down a difficult path very young.

"I actually found some of my mom's stash while she was in jail, and was keeping it away from my grandmother, who was bribing me for it," he said. "I ended up selling it to her, actually, and that's how it started — real close to home. At that time, I had to be 11 or 12."

As the years ticked on, he watched the family business grow in depth and scope. Drug dealers not much older than the 14-year-old patriarch regularly dropped by the house, and he watched as his mother spent their government checks on crack, when she wasn't in prison.

When she was, his grandmother handed over the money all the same.

"Right away, I knew I needed to reverse that situation," he said. "If it was gonna be happening, my logic was to benefit from it at the time, to keep the money with us. I was unaware of any other options, really, although they existed, I'm sure."

As was nearly predestined, he dropped out of high school and joined forces with his mother and grandmother. They were "thick as thieves," he said, "running our drug house on an hourly basis, serving it out the window. It was everything you see in the movies."

But then, his uncle got shot. And then his friend.

Mr. Morton spiraled.

"It was like, 'Why him?' I was literally right there. I had just gotten dropped off and he got killed. I was always with him, it could have just as easily been me," he said. "At that time, I started living on the run. I was getting a little more reckless and careless in my dealings in the streets."

He sighed. "It culminated with me getting caught in a hotel room as a result of my mother—accidentally, I think," he said. "She unwittingly brought a confidential informant with her that I kind of knew and warned her against."

It was February 2004. He was 19. And even when he was arrested, he had a backpack full of books.

"I thought I was hustling to find my way and get to an art school," he said. "In my mind, I was trying to come up with the money. Even then. Even then."

A decade later, the 11-year sentence he received would be ruled as "racially motivated and unconstitutional," like many drug convictions at that time.

But then, it was his reality. And any anger Mr. Morton felt, he transformed into redemption.

"You know, it’s weird because while on one hand, it was like, 'F--k'—I mean, 'Dang'—'I'm going to prison,' on the other, it was a sense of relief," he said. "I was actually kind of happy that it was all ending. I could relax. Up until that point, I was just self-destructing. At any given moment, I could have lost my life and so, deep down, I longed for that opportunity to escape. I felt like I was in, just, hopelessness — poverty-stricken hopelessness."

"You know, it’s weird because while on one hand, it was like, 'F--k'—I mean, 'Dang'—'I'm going to prison,' on the other, it was a sense of relief," he said. "I was actually kind of happy that it was all ending. I could relax. Up until that point, I was just self-destructing. At any given moment, I could have lost my life and so, deep down, I longed for that opportunity to escape. I felt like I was in, just, hopelessness — poverty-stricken hopelessness."

He had a choice. Continue the pattern of drugs, poorness and prison, or change.

He chose the latter.

"People expected me to be just another statistic. It started a fire in me," he said. "I started looking at it as an opportunity, brilliantly disguised as a setback. Early on, I had decided that I would nurture and develop my craft — right away, before I was even sentenced. I took advantage of it right away, literally, from day one. I had already resolved to have that singular focus of fine art. And I obsessed over it."

The proof still lives in the six prisons where he was held, from maximum security — "It was a first-time offense, and I'm in there with, literally, terrorist bombers," he said — down to minimum security. By cooperating at every turn, the executive staff allowed him to splash murals on the cold walls, and even commissioned portraits themselves.

So did the families of his fellow inmates.

"I realized I could make a living for myself when I was away. When I wasn't painting, I would always be studying," he said. "There was a deep, deep period of growth and development in the most intense way. Sometimes, I found myself hoping I'd get released soon, before I'd developed as much as I could. But I would often find myself content by the fact that I knew I wasn't as developed as I wanted to be before I got out, anyway."

In 2013, after serving 85 percent of his sentence, he found himself a free man — albeit on parole — and released to a new city, Atlanta. He had gone in a boy and came out a man. He hadn't even bought alcohol legally yet.

He arrived at the local halfway house with a six-foot easel and a new determination. While the former inmates watched television, he would draw them. While they complained about the economy, he got to work. Within a week, he had a job at a gym, kickstarting a serendipitous sequence of events that would eventually lead him to Sag Harbor.

"Choosing life over death, choosing success over failure, it wasn't a choice at all," he said. "I wasn't going to give up, you know? I wasn't going to give up, that was not going to be the end of me. I felt like I was on a world stage. Here's my chance, I'm going to take off sprinting from the gate."

What happened next was completely strategic, Mr. Morton said. He walked into a private gym, in an affluent area, and asked for a job as a personal trainer. He even offered to work for free.

Owner Andrew Hemming couldn't say no, especially after hearing Mr. Morton's story, and created a position just for him — primarily manning the front desk and helping out with odd jobs around the facility.

Immediately, in the halfway house, the artist painted a huge portrait of him.

"I knew if I could do a good job on that painting and hang it in the gym, the right person would see it and it would lead to more opportunities," he said. "Sure enough, that's exactly what happened."

"I knew if I could do a good job on that painting and hang it in the gym, the right person would see it and it would lead to more opportunities," he said. "Sure enough, that's exactly what happened."

The portrait caught the eye of architect Keith Summerour, who sought out Mr. Hemming and asked, "Who painted that?" the artist recalled.

"You know, George," Mr. Hemming had said.

"George? George who?"

"The guy down there cleaning those toilets," he had replied. "You know, George."

"No way," he said, immediately leaving the painting to find Mr. Morton, who was practically waiting in the eves. Little did he know that Mr. Summerour served on the board of the Florence Academy of Art, and insisted that Mr. Morton apply.

He did. And he was accepted to study in Italy, except his parole did not allow him to travel. No exceptions.

"Right when I thought my dreams to get academic training were denied, I was shortly after informed that The Florence Academy was coming to the states to open their inaugural U.S. branch, and that I was invited to come be one of the few students to christen the new space," he said. "At this point, I knew there was a force behind this, a force of positivity, in a predestined way."

But fate only goes so far when faced with a heavy tuition bill and zero savings. With the help of Ms. Grenning — who became a fast friend and supporter of Mr. Morton early on—he launched a Kickstarter campaign called The George Morton Project, which raised $14,055 in 30 days.

It was enough to get him started, but not enough to let him graduate.

By Christmas, Ms. Grenning said she hopes to raise the $12,000 it will take for Mr. Morton to complete his studies. This summer, he will finally travel to Florence, Italy — after the gallerist worked with his lawyers and wrote a heartfelt letter to the presiding judge, requesting that he be released from his 10-year parole, which was recently granted.

"Although counter-intuitive, it's my guess that Morton's struggles during the first third of his life have created a sensitivity and emotional depth that will always be reflected in his work," she wrote. "Ironically, this sets his pathway above many of [his] fellow artists. I have dedicated the last 20 years to helping find and develop young talent, and when I find a talent like Mr. Morton, I feel strongly that we should all do what we can to give them wings to soar to their own highest level."

These days, the artist spends between 10 and 14 hours a day in his Atlanta studio, nearly seven days a week, surrounded by graphite, charcoal and oils, meeting the needs of an “impossibly rigorous program,” he said.

As he works, he finds himself inspired by the world of realism, the full range of human emotion and capturing it on a canvas. As he moves, he is truly free—free from his childhood, free from the drug war, free from prison, free from his darkest memories and free from the mental bondage of failure and low expectations that plagued his drug-infested community.

It is an inescapable reality that the majority of his relatives are still entangled within to this day, he said.

“Unfortunately, my siblings haven't been so blessed. We are all such a product of a very hopeless and hostile environment,” he said. “Those that are still blessed to be among the living are also serving as my inspiration. They are observing my every move, and I work hard every day to be the best example of human potential unleashed as I can possibly be. They, along with many others in underprivileged communities, are counting on me and I intend to let my life serve as a beacon of hope and inspiration.

“When I look back on how far I've come, I feel it is nothing short of a miracle,” he continued. “I survived a massacre. So many people who I believe to be far greater than me didn't make it to see this day, and so I am inclined to believe that I am here for a real reason. That reason is becoming more clear with each day.”

For more information about George Morton, visit georgeanthonymorton.com.