While John Kenneth Galbraith might have been referencing art and aesthetics when he observed, with admirable idealism, that beauty, dignity, and pleasure are “questions that are beyond the reach of economics,” it’s clear that he never ran a gallery on the East End during a massive global economic collapse.

Nonetheless, even as spaces such as Walk Tall Gallery and the Sara Nightingale Gallery seem to have recently succumbed to the forces of fiscal Darwinism, new galleries inexorably seem to pop up in their place, economically charting like some sort of exotic “two steps back, one step forward” dance move.

The latest step in this financial cha-cha of exhibition spaces is the Delaney-Cooke Gallery in Sag Harbor, perhaps not coincidentally the only village on the East End where new galleries seemingly continue to flourish in the face of retrenchments just about everywhere else.

One interesting aspect of this new entry is in the bifurcation of the gallery itself, with the front room hosting an exhibition of a number of local artists while the rear is dedicated to the archives of the late Jerry Cooke, the noted photojournalist, whose widow, Mary Delaney, is the gallery’s director.

In the front room, one could be excused for describing the exhibitors as a lineup of the usual Sag Harbor suspects, with a number of them apparently émigrés from Gallery Merz just across the street.

Of particular interest are works by David Slater, whose painterly figurative motifs are never absent a near-overload of pictorial information, but which are likewise never absent a narrative stream that is as entertaining as it is intellectually challenging. This is the case whether considering the overtly political feminist impulses in “Azteca” (Roland Print) or the underground cartoon-like rendering, “The Big Kahuna” (gouache and colored pencil), with its explosion of colorful and suggestive imagery that constantly seems, upon continual reflection, to offer new hints about the artist’s intent in plot and story line.

Warren Padula’s “Space Travel” (pigmented ink on rag paper), by contrast, conjures narrative elements through a spare and dreamlike juxtaposition of images that is notably ambiguous in its amplitude but nevertheless offers the viewer an opportunity to divine a story line through the contrast in lights and darks and the distinctions drawn via Mr. Padula’s insistent repetition of imagery.

Rocco Liccardi’s “Bahia” (collage and paint on printed paper), on the other hand, is considerably more pictorially unrestrained by comparison, eschewing immediate narrative yet nevertheless evoking a certain literary quality in its abstracted use of letters and numbers within the rhythmic composition.

Rhythms also play a dominant role in Dominick Cantasano’s “Ham and Eggs” (oil and pastel on paper) in the artist’s juxtaposition of color and line to create a ferocious rush of movement that seems barely contained by the borders of the work. Using overlapping geometric forms to imply a degree of depth, the artist further accentuates this sensation by an attentiveness to delicate patterning and a gentle contrast in brush strokes and gradations of color.

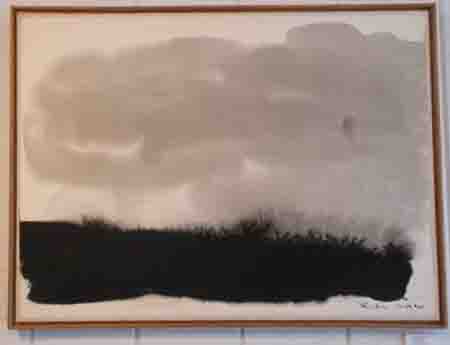

Also of particular interest are Beth Giles’s “Red Angle” (etching/monoprint), David Slivka’s “Untitled” (India ink wash), Audrey Lee’s “Three Girls” (mixed media), and Michael Knigin’s “Seminary Ridge II” (pigmented ink on rag paper).

In the gallery’s rear room, a space that is unfortunately too cozy for the quality of the work on view, are the photographs of Mr. Cooke, whose images are familiar to anyone with more than a passing acquaintance with photojournalism and the impact of the remarkable stable of photographers who once worked for Time-Life.

A former director of photography for Sports Illustrated and president of the American Society of Media Photographers, Mr. Cooke made photographs that are powerful for both their historical resonance and their masterful use of composition. This kind of impact is apparent whether an image dynamically expresses emotion, as in his portrait of the recently defected Mikhail Baryshnikov, or offers a profound and moving narrative, as in the group of children playing in a military cemetery.

Of most interest to this viewer, though, is Mr. Cooke’s 1968 nude portrait of the 17-year-old gymnast Cathy Rigby, an adolescent crush of mine when the image appeared in Sports Illustrated but which was artfully, and maddeningly, blurred to reflect the more delicate, if not prudish, sensibilities in mass media of that period.

Here produced with a clarity that sharply underscores the remarkable parallels between dancers and gymnasts in their grace, agility and physical dignity, the image aroused a number of emotions. Most immediately, I felt a measure of resentment at the mores of a society that had obscured this image from me in my youth, when the use of a fog filter suggested that sharper focus would serve only some sort of prurient interest, and thus detracted from those aesthetic elements that give the image its inherent power.