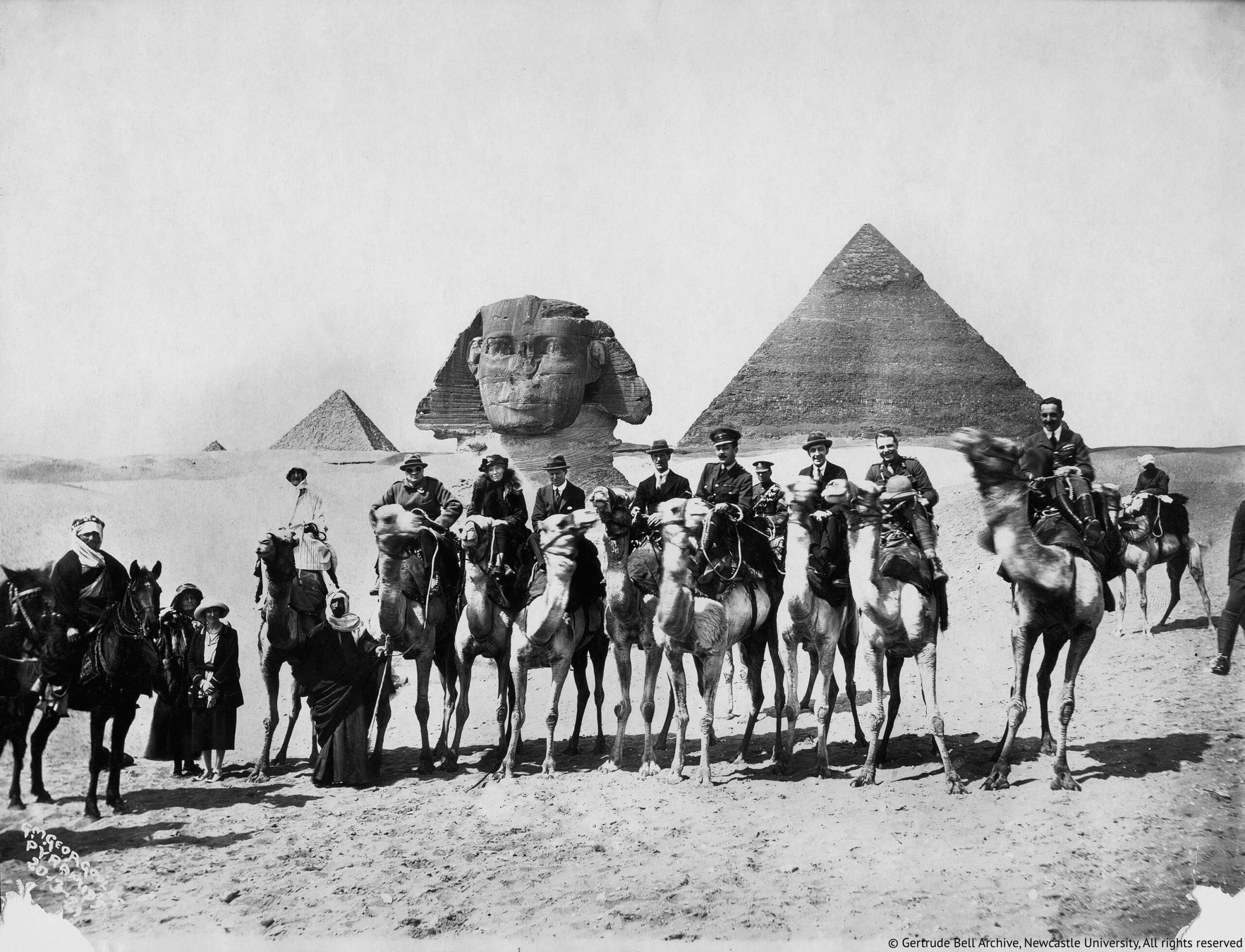

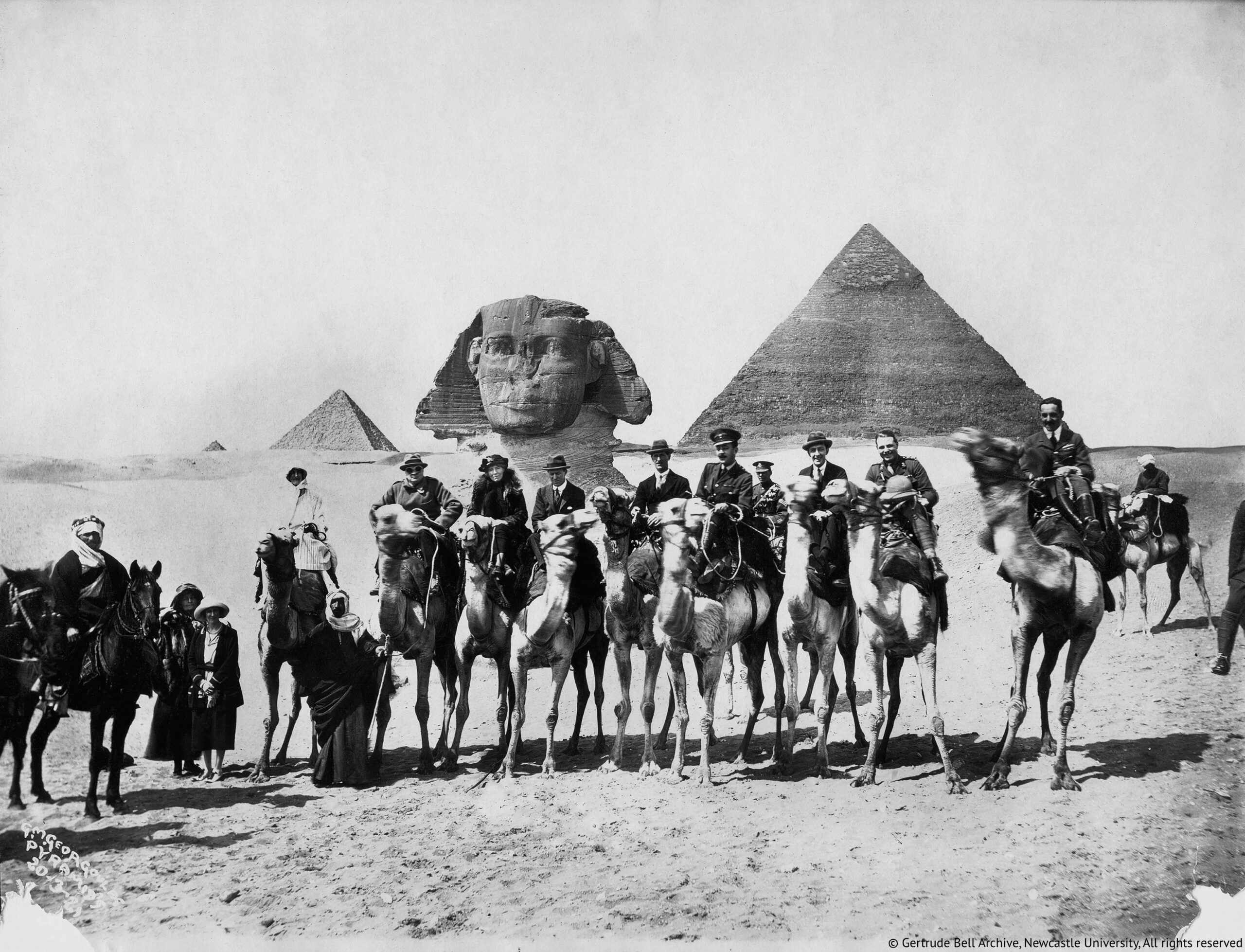

[caption id="attachment_74985" align="alignnone" width="1024"] Courtesy image from "Letters to Baghdad"[/caption]

Courtesy image from "Letters to Baghdad"[/caption]

By Annette Hinkle

Over the course of the past two decades, U.S. involvement in Iraq has developed into a long, complicated and tragic story. But it's a story with roots dating back a century or more before our military ever set foot in the country, and one that began with the arrival of another foreign power — the British.

With the end of World War I in 1918, so too came the end of Ottoman rule over Mesopotamia and the region we know today as Iraq. When British forces captured Baghdad from the Ottomans in 1917, they did so with help from the Arabs who were promised an independent state in exchange for their assistance. But that state remained elusive as the British rushed in without a comprehensive political strategy for the city of 200,000 (including its 80,000 Jews) and the surrounding region which was home to many Arab tribes. When the British appeared to settle in for the long haul, unrest grew leading to the rebellion of 1920 and concerted efforts to finally form the country of Iraq.

The problems we see in the region today are eerily similar to those encountered by the foreign British powers who sought to govern and ultimately set Iraq on the road to democracy in the early 20th century. Sectarian differences, tribal allegiances and a desire to curry favor with the British and the West’s unquenchable thirst for oil all played into the making of the country.

This Sunday evening at 8 p.m. at Bay Street Theater, Hamptons Take 2 Film Festival will screen “Letters From Baghdad,” a documentary by Sabine Krayenbühl and Zeva Oelbaum that tells the story of the formation of Iraq through the eyes and words of an unlikely champion and ally of the Arab tribes — a British woman named Gertrude Bell.

The Oxford-educated Bell understood the region, and the potential for problems, like few other westerners. For years, she had procured her own camels and organized travel parties that ventured deep into the desert regions of Arabia where she came to know the sheiks, their people and their customs. Along the way, she wrote extensively about her travels in books and letters to her father and stepmother back in England.

“Gertrude Bell writes a lot about her experiences in the desert and the sheiks’ tents where she is perceived to be kind of a queen … an anomaly,” explained Oelbaum. “She was such a surprise. We feel like she got much further in terms of relationships with the Arab tribes than a man could’ve gotten.”

“Because she was a woman, she was also not perceived as a threat,” said Oelbaum adding that Bell was a fluent Arabic speaker who picked up dialects very quickly. “It was a combination of all these things. She was not accompanied by a European man, additionally surprising was she dressed like a British woman. She had her perspective and felt you need to respect your own background so you can appear as an equal.”

“One of the things that fascinated us from the beginning of this project was the contemporary relevance on so many levels,” added Krayenbühl. “Women breaking through male society, the Middle East falling apart because of things that happened in the past. When we first started this project, we had no idea things would develop to the degree that they have.”

For any filmmaker, recreating 1900s Baghdad would be no easy feat. While the filmmakers relied heavily on Gertrude Bell Archive at Britain’s Newcastle University — which holds 1,600 of her letters — to tell the story, for the visuals they set out to use archival footage, something they weren’t sure would be possible given that the events depicted took place so early in the days of movie technology.

“We both love archival footage and finding amazing old footage,” said Krayenbühl. “We were so surprised the first archive we reached out to had great footage of these round coffer boats you see in the film.”

“What was interesting, but didn’t occur to us, it was the dawn of cinema,” added Krayenbühl. “The movie camera was a brand new medium and people who had means would shoot left and right. It turned out there was quiet a wealth of stuff. Some people asked, ‘how did you shoot scenes in Baghdad?’ We didn’t. We asked the archives to go back and rescan negatives where possible.”

As a film, “Letters From Baghdad” began eight years ago while Krayenbühl and Oelbaum were working together on a documentary called “Ahead of Time” about foreign correspondent and journalist Ruth Gruber, which takes place partially in the Middle East. Oelbaum, the film’s producer and Krayenbühl, its editor, realized in their discussions that they had both read “Desert Queen,” Janet Wallach’s biography of Gertrude Bell and agreed she would be an interesting subject for a film. But it took another three years for their schedules to align and during those years, the situation changed greatly in Iraq.

“At first, Obama was pulling troops out of Iraq and it was not so much in the headlines,” Krayenbühl said. “But then came Isis, Syria, and the Kurdish independence movement.”

The different ethnic and religious groups in the region, including the Shia, Kurds and the ruling Sunni minority, have long been at the core of difficulties in the West’s attempts to manage the area and the same was true in Gertrude Bell’s day. Bell was a contemporary of British war hero T.E. Lawrence (the model for Lawrence of Arabia), and Civil Commissioner Sir Percy Cox. The three of them were part of the mission to define Iraq’s territory taking into account the differing views of the various tribes.

“I think in that, way Gertrude was very much an advisor,” said Oelbaum. ‘The borders where she was most crucial were between Saudi Arabia and Iraq. That’s what she knew. She consulted with the tribes and they came to her office and discussed it.”

But ultimately, it may have been that the British goal of uniting the disparate peoples of Mesopotamia in a single country with defined borders was never going to be a realistic one.

“The British approached Iraq how they approached all other colonial regions,” said Oelbaum. “It’s all about central authority. The benefit is there are schools, roads and hospitals that all can access. But that wasn’t the way the tribes were set up.”

“It’s easy for us to say things might have been better with Gertrude having more input, but we don’t know if that’s the case,” she added. “What we do know is the southern borders of Iraq are more stable — and those are the ones Gertrude drew with consultation with the Arabs.”

Gertrude Bell died in 1926, and in addition to her other work, led archeology expeditions throughout the region. Her archeological finds became the basis of Baghdad’s National Museum of Iraqi which she founded — the same museum looted of its antiquities during the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq.

The event offered a tragic postscript to the life and legacy of Gertrude Bell, one that speaks to the unfortunate track record of western powers in the Middle East. When asked what she thought Bell’s vision would have been for Iraq had she been able to make even more decisions in the region, Oelbaum responded:

“I think that she would have made similar mistakes. She wanted the Kurds to be included and the Sunnis to be in control. Gertrude Bell felt that diversity on the provisional cabinet would lead to people working together. She had the point of view of someone who was from a monarchy, a more democratic point of view.”

“What was actually revealed to us, which was way too much detail for the film, having all the different groups represented in the cabinet had the opposite effect,” said Oelbaum. “All of a sudden people used to living separate but equal, were all vying for the favoritism of the British.”

Which leads to the question that has dogged the U.S. for so many years. Is it possible to impose western-style democracy on a region made up of so many disparate tribes?

“The idea of nation building is really a tricky one,” admitted Oelbaum. “I think we outline that in the film to show the difficulties — it may not be a western strategy that should be pursued there.”

“Letters From Baghdad” has already been screened at the Beirut International Film Festival, where it won the Audience Award. This month, it will screen in Amman, Jordan and later in Istanbul, and the filmmakers are now in discussions to screen it in Iraq.

“We’re thrilled and hoping it will happen and the situation gets better there,” said Sabine.

“Letters From Baghdad” will be screened at Bay Street Theater on Sunday, December 3 at 8 p.m. as the Hamptons Take 2 Film Festival’s “Sunday Spotlight Film.” Admission is $25 which includes a wine reception and Q&A afterwards with the directors led by Janet Wallach author of the biography of Gertrude Bell. Visit ht2ff.com for tickets or more information. The festival runs Thursday, November 30 through Monday, December 4 at Bay Street Theater. A festival pass for all films is $150.

Prior to the screening of “Letters From Baghdad,” Wölffer Kitchen, 29 Main Street, Sag Harbor is offering a wine dinner inspired by the film. Featuring a Middle Eastern menu, the dinner begins at 5:30 p.m. and each course will be paired with select Wölffer wines. Ticket price is $116 which includes dinner, wine and admission to the screening. A portion of the proceeds will benefit the Sag Harbor Cinema Arts Center and Hamptons Take 2 Documentary Film Festival. Reserve online at eventbrite.com/e/letters-from-baghdad-wolffer-wine-dinner-tickets-39732611310.

Wine Dinner Menu

Amuse

Hummus Pitryot | grilled pita, hen of the woods mushroom, dill

Grapes of Roth Dry Riesling 2014

First

Fresh Lentil Soup | fresh herb yogurt

Wölffer Estate Classic White 2015

Second

Braised Lamb and Cauliflower | persian wedding rice, prunes, apricots

Wölffer Finca Brau 2011

Dessert

Ma'amoul Tartlets | dates, apricots, pistachios

Wölffer Estate Diosa Ice Wine 2014