[caption id="attachment_59519" align="alignright" width="800"] Students in Watermill's Young Artist Residency Program attend a guest workshop led by The Hutto Project at the Watermill Center in January of 2017.[/caption]

Students in Watermill's Young Artist Residency Program attend a guest workshop led by The Hutto Project at the Watermill Center in January of 2017.[/caption]

By Michelle Trauring

Kate Eberstadt stood up in front of the crowd, 170 pairs of eyes looking back into hers. They were curious, probing. Some seemed almost as scared as she was.

She swallowed her nerves and began speaking in English, one sentence at a time. She paused after each, waiting as the translators relayed her message in Arabic, Farsi, Kurdish and Russian. And as she waited, she looked around the room.

It was a high school basketball gymnasium in the heart of Berlin, empty but for the bleachers pushed up against the walls and a sea of bunk beds. There were walls, no privacy and no day-to-day structure. This was their home—an emergency refugee camp, home to displaced families from Syria, Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Palestine and Moldova. This was their reality.

Her attention snapped back to the crowd. As the refugees listened, Ms. Eberstadt watched a ripple effect of understanding and relief wash over them. Then, they began to smile.

Soon, the language barrier would no longer be an obstacle. They would communicate instead through song—the beating heart of The Hutto Project, a music and performance education program for children age 3 to 14 that Ms. Eberstadt founded and collaborated on with documentarian Brune Charvin and conceptual artist/writer Khesrau Behroz.

Together, they worked with 25 children for two hours a day, three days a week for six months in the CPR classroom of a Red Cross building. For the children, it was a form of escape—physically, emotionally and creatively. For the first time in a long time, they were free to just be kids.

But for the three friends—who met during The Watermill Center’s International Summer Program, and are now in residency at the avant-garde laboratory—it was a leap of faith, and one that has left them forever changed.

“It feels right to be back here where everything started,” Ms. Eberstadt said during a telephone interview from the Watermill Center. “We’ve gotten the opportunity to teach a few classes since we’ve been at Watermill to a group of children from the local schools who come every Tuesday, a really different group of children.

“But I was really, really impressed with their empathy,” she continued. “We showed them the footage and asked, ‘Do you know what a refugee is? Do you have an understanding of what’s going on in Europe?’ And the first questions they asked were, ‘Do all of these kids have families? Do they still live in this camp? What is their future like? Are they going to be able to see us, too?’

“It was moving to hear a whole new group of kids singing the same songs, and it doesn’t end up being that much different because at the end of the day, it’s a bunch of children’s voices. It kind of makes you think about the possibilities of bringing people together that way.”

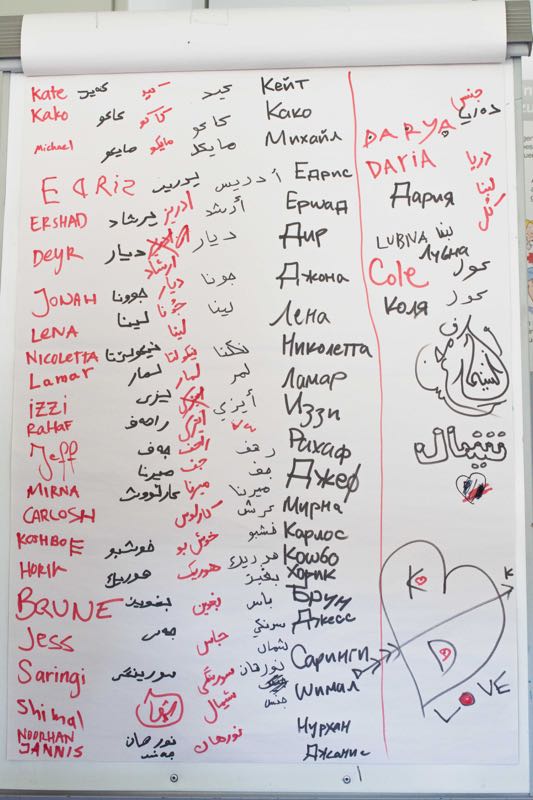

[caption id="attachment_59521" align="alignright" width="438"] The Hutto Project sign-in sheet: in English, Kurdish, Farsi, Arabic and Russian.[/caption]

The Hutto Project sign-in sheet: in English, Kurdish, Farsi, Arabic and Russian.[/caption]

The Sag Harbor Express: The Hutto Project is named after the late Benjamin Hutto, your music teacher in high school. What was he like?

Kate Eberstadt: He was a force to be reckoned with. He was a teacher unlike any other that I’ve met. He could do anything musically and he decided to use his gifts to focus on education. It’s just amazing how much of a difference one person can make on your life. I was 14, I was very musically inclined already, but I really did not understand how to sing properly and how to listen in a musical way. I felt he took me under his wing and he saw options and possibilities that I couldn’t even see for myself.

When you have a teacher like that, you don’t forget them and you don’t forget how powerful it is to be seen like that. When I had the opportunity to go to Berlin, I knew I wanted to try to help with the refugee “crisis,” and that I would want to do at least a fraction of what he had done for me.

I imagined, what if I was living in those circumstances, in an emergency refugee camp, not being in school, not really looked after? There’s 8,000 people living in one building, what would have been helpful for me, if I was 12 years old? And I did think of Mr. Hutto in that moment, and what would have been helpful for me is if somebody came and ran a music performance class. So that’s what we did.

What were your first thoughts upon entering the emergency refugee camp?

Ms. Eberstadt: I was kind of scared, actually, when I first got there and presented the project because I had absolutely no idea how people were going to respond. And I had never done anything like this before in my life. I just had a feeling in my heart that this would be really beneficial and faith in that, because it was what my teacher had taught me. I had no idea how it was going to pan out. But being there and seeing the reaction was confirmation of what I had hoped to be true.

Over the course of the six months, was there a particular moment that made you pause and say, “Yes, what we’re doing is right and has an impact”?

Ms, Eberstadt: The first thing that comes to mind is the first time one of the kids asked me if he could show something to the class, like a show and tell. He was 14, and he had downloaded an app on his phone of a keyboard, and had been practicing a song—even prior to our program. That was something he would do in his endless time at the camp. You’re sitting around, waiting and waiting to get an apartment, asking, “When do we leave? When do we go to school?”

There was always a lot of noise, people talking in the class, and there were so many languages going on. There was always a little bit of background music, background babble. And the second he started to share something personal like that, there was complete silence in the room. Everyone realized the gravity of the moment, of somebody really breaking the music classroom routine and sharing something personal. He played on the keyboard for 10 minutes and every single kid was just silent.

I had not considered how personal music is, how much of a privilege it is to get to play music, even just to listen to it. Some of the families I met had trouble listening to music from home.

What other direct impacts of the refugee migration did you see on the children?

Ms. Eberstadt: There was a girl. Her experiences leaving home had left some physical effects on her body. She was a burn victim from Syria. She was 6 years old. I could tell she was actually interested in music, but she just had a lot of trouble participating. She was very shy and she wouldn’t actually vocalize any words. She would whisper everything if she was even participating at all. But she was very engaged when she was in class. She was watching and sitting under her chair. For a student like that, I could empathize a lot. I could see her interest in music and I really hoped that we could work together and help nurture that.

A month into class, I will never forget the first time she raised her hand. I was looking for volunteers to do a movement exercise, and all of a sudden in the corner, I saw this one hand raised up that I had never seen before. I was like, “Oh, okay, are you ready?” From that moment, she became a really active participant in the class. She led this effort to draw the “tah” quarter note all over her arm and the other kids’ arms. It was really special to get to see a breakthrough like that.

What was it like saying goodbye to them?

Ms. Eberstadt: Not easy. Not easy at all. They’re kids, right? So we understood very well that we were leaving and we had explained we were leaving, but I don’t think the message had been fully picked up by everyone. Brune prepared a goodbye gift, which was a printed photo from class. It was not easy, but we can keep in touch with some of the students through the internet.

The camp has been evacuated and shut down, so they’ve all been moved to different places. Some of them are living in apartments now with their families. Some of them are moved into new camps. And a few of them have not been admitted into Germany, so they had to go home.

Do you feel this experience changed you, now that you’re back in the United States?

Ms. Eberstadt: Definitely. How is a hard question to answer eloquently. To be totally honest, it’s really hard to have an experience like this and to not continue to do it. I felt like when I first got there that I’ve been waiting my whole life to do something like this. I never felt the work I was doing was the work I was meant to do. And in some ways, I have even more questions now than I did when I got there. Where do we go from here? How do we engage more people in projects like this? How can we tell the story?

So now you’re trying to figure it out that next step?

Ms. Eberstadt: Yeah, exactly. This past fall when I left Berlin, I had a lot to think about. I went home to D.C. and I recorded an album in my basement with my sister, who is also working on the project. And so 2017, on a personal level, I’m definitely releasing that work.

But we’re really just at the beginning of telling this story. In order to move forward and do the next project, I want to make sure I fully understand the full scope of the one we just did—what could be improved, what worked best, what didn’t. I want to be careful about it. This was very precious, the experience we had. And I want to make sure that story is told, and honored, as best as possible.

What do you think Mr. Hutto would have to say about this project?

Ms. Eberstadt: Here’s something that’s personal. This might surprise you, or maybe not: when I was in his class, I was shy, but by the end of high school, I was kind of an authority problem. He and I got along really well, but he would really not give me a break about discipline. He was teaching me in some ways more about how to work as a team player. That, to me, was his main work with me—not even the music. I didn’t even understand it at the time.

If you were to look at how we worked in Berlin and what we were able to do as an ensemble, rather than individuals, I was really just replicating a lot of the stuff he taught me. I would love to have a conversation with him now like, “Hey, so, you were right. And, also, thank you.” I don’t know what he would have to say, but I would be very curious to hear his opinion. Maybe someday we’ll have that conversation.

The Hutto Project will host a workshop during The Watermill Center’s Family Day on Saturday, January 28, from 1 to 4:30 p.m. at the laboratory in Water Mill. Open to children age 7 to 12, and registration is required. For more information, call (631) 726-4628, or visit watermillcenter.org. For more information about The Hutto Project, visit thehuttoproject.com.