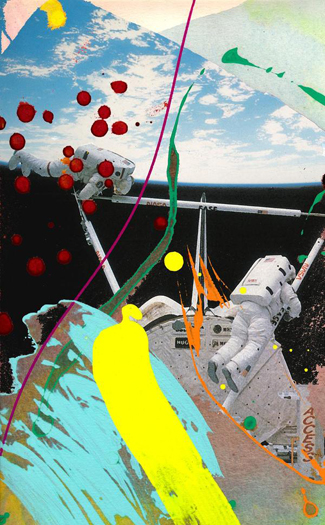

A space shuttle soars above impossible landscapes. An astronaut floats among bands of color that exist only in the imagination.

An image of the German diarist Anne Frank (1929-1945) is enclosed in a diamond shape. The word “Radioactive” provides her ceiling; a cracked desert behind two pages of her famous diary provides her floor.

These very disparate artworks have one thing in common: they were all made by Michael Knigin of East Hampton. It seems these days that Mr. Knigin and his artwork are on a roll.

The two space-themed pieces were accepted into the permanent collection of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., in August. The collaged montages are the first artworks drawing on digital technology to be made part of the museum’s permanent collection.

One of Mr. Knigin’s Anne Frank pieces was part of an international exhibition celebrating what would have been Anne Frank’s 80th birthday. The show was sponsored by the Peter Wilhelm Art Center and held in a former synagogue in Budapest, Hungary. Running from October 6 to 22, “Anne Frank In the Artists’ Eyes” (www.proartibus.com) featured 29 artists from around the world.

Diverging once again, Mr. Knigin, whose work is already hanging in two other Las Vegas hotels, will have a series of paintings featuring flowers in rooms at the Mandarin Oriental Hotel in Las Vegas. One painting bound for the glittering desert hot spot features a lone purple flower bursting onto a black textured background. A slip of starry sky and silver moon peek from above.

The grounds outside the Mandarin Oriental, which is due to open in December, feature sculpture by Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen along with works by other renowned artists. The residential hotel’s art collection will include works by Maya Lin, Jenny Holzer, Frank Stella, Henry Moore and others.

Considering all three of these recent successes, it seems that contemporary critical opinion has caught up with Mr. Knigin’s artistic vision, which combines traditional techniques with computer technology to create limited edition prints and paintings. Building on the process he used for his early works, which drew on the techniques of montage and collage, Mr. Knigin has always combined disparate images to create something new.

Reflecting his devotion to fine art lithographic and silk screen printing since the late 1960s, Mr. Knigin’s early artwork featured realistic drawings with advertising graphics or other icons and images taken out of context for his completely handmade paintings. In the early 1990s, when Photoshop was released, he made the natural leap from hand-cutting images to scanning them into a computer. Multiple manipulations of compositions were now easily accomplished using the software program.

Today, using Photoshop to create art is nothing new: digital art is everywhere, and art created with an iPhone has been featured on the cover of at least one prestige magazine. Even so, Mr. Knigin distinguishes his work from the digital revolution.

“My art is not digital,” he said. “I’m a montagist or a collagist. I use Photoshop as a tool; it’s not digital art. There’s a difference.”

Mr. Knigin overlaps and assembles painted and photographic pieces to form the visual elements of his work. After the pieces are aligned in a composition, then Photoshop is used to manipulate, resize and change the work until it reaches its final form.

“I like to take the recognizable and change it into something new and unexpected,” he said.

He also strives to combine the emotions and subconscious with concrete reality and the intellect in his work.

Each piece begins with an abstract painting in which emotions run free in sweeping brush strokes. In many instances, the painting is torn and divided. Different sections are scanned into the computer for incorporation into the artwork being made. Pieces of photographs are divided the same way or extracted with Photoshop.

The “recognizable” elements—such as fireworks, stars, astronauts, flowers, the moon, Nazi concentration camps, angels, demons and famous sculpture—are added into the artwork as signposts. The interpretation and what the relationships mean is left to the viewer, Mr. Knigin said.

Through the years, Mr. Knigin has created databases of images made from paintings and photographs. In this way, a piece can be created from overlapping and assembling imagery from new paintings and recent photographs or from his storehouse of existing imagery in both mediums.

Popular images and contrasts between manmade objects and natural elements run through his art. The dehumanization of mankind and contemporary lack of appreciation for beauty and elegance are frequent subtexts. Mr. Knigin hopes that his artwork communicates ideas and raises questions by using dramatically opposed imagery and extreme contrasts.

Mr. Knigin tends to create works in a series until his interest is sated. Some of his series deal with such subjects as Anne Frank, the Holocaust, flowers, abstract landscapes, birds, fish, horses, vintage nudes, Japanese woodblock classics, social commentary and more.

Mr. Knigin’s NASA series stems from his time as part of the NASA Art Team. In 1988, he was invited to the Kennedy Space Center to interpret NASA’s first return to space after the Challenger disaster. In 1991, Mr. Knigin was part of a group of artists interpreting the touchdown of Atlantis in California.

It’s possible that his time spent with NASA helped open the doors for the recent acceptance of his artwork to the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. “They probably knew my name from my time with the NASA Art Team,” Mr. Knigin commented. “It’s hard to say. All I know is this is the first time they’ve accepted artwork created digitally. It’s a big deal.”

Mr. Knigin’s art is part of collections held by the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Brooklyn Museum, Carnegie Mellon Institute, the Israel Art Museum, the Library of Congress, the Japan Society and many others. His work can be viewed at www.michaelknigin.net. For information, call 329-3923.