[caption id="attachment_67301" align="alignnone" width="800"] Richard Estes (American, born 1932), Hotel Empire, 1987, Oil on canvas, 37 ½ × 87. Meisel Family Collections, New York.[/caption]

Richard Estes (American, born 1932), Hotel Empire, 1987, Oil on canvas, 37 ½ × 87. Meisel Family Collections, New York.[/caption]

By Michelle Trauring

Terrie Sultan and Chuck Close chat often. And, when they do, photorealism almost always comes up.

It’s not that the artist considers himself a photorealist. In fact, he vehemently rebukes it, despite his renown for large-scale portraits.

His process is different than capturing a moment with a photograph and expressing it through an alternative medium — the definition of photorealism, he has explained to the Parrish Art Museum director. But Sultan still decided to include his work in the upcoming exhibit “From Lens to Eye to Hand: Photorealism 1969 to Today,” opening Sunday at the Water Mill museum, because he is regarded as a photorealist in the art-historical canon.

And because of a point he once made.

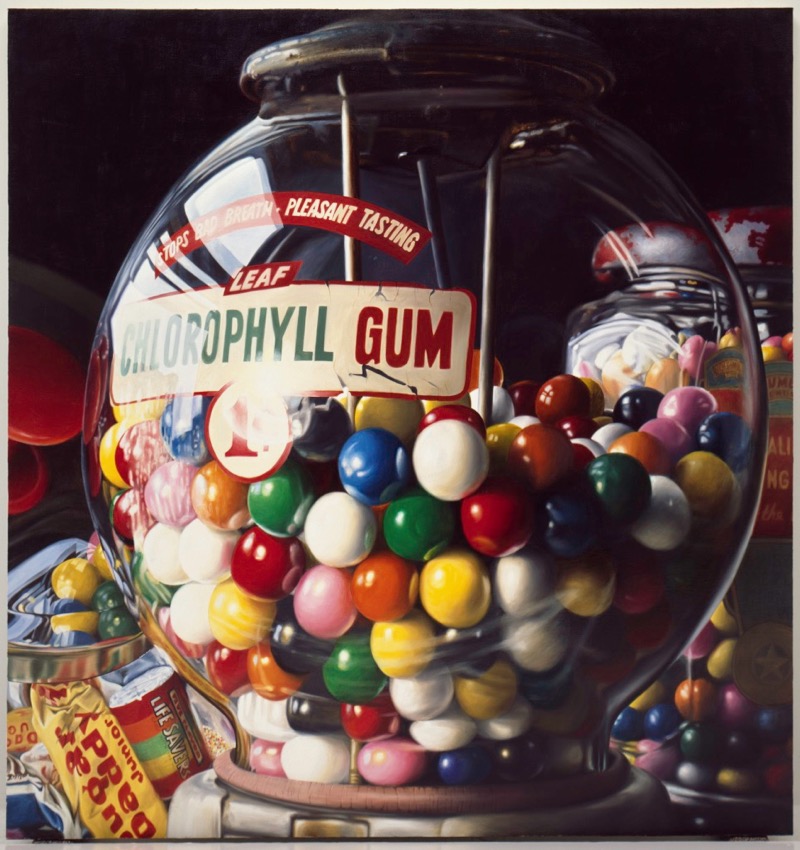

[caption id="attachment_67298" align="alignright" width="399"] Charles Bell, Gum Ball No. 10: "Sugar Daddy", 1975.[/caption]

Charles Bell, Gum Ball No. 10: "Sugar Daddy", 1975.[/caption]

“Chuck said to me, ‘Look, the thing is, if you’re interested in trying to describe what your eyes see, something that you can’t express visually very easily, think about the impossibility of painting blur,’” Sultan recalled. “‘You can’t paint blur, because you can’t see blur except out of the periphery of your eye. If you look at the place that’s blurry, your eye will make it in focus. If you can see it, you can paint it, but the only way you can paint blur is to see a picture of it, otherwise your eye will make it so you can’t see it the way you want to.’

“And to me, that’s so intellectually engaging,” Sultan continued. “And trying to parse all of that out as you’re looking at those pictures, it really, to me, is a compelling way of thinking about what we see, how we see it, and how we interpret it.”

Sultan really got to thinking during a visit with Louis Meisel, a major collector of Photorealism, she said. When he showed her two paintings by Audrey Flack — “Wheel of Fortune” and “Kandy Kane Rainbow” respectively — he asked her if the Parrish would like them.

“We were absolutely thrilled to accept,” Sultan said, still giddy.

Meisel invited her to look around some more and brought her into his study, where she saw a collection of 60 photorealism works on paper, mostly watercolors, dating back to the 1970s. Works that had never been shown to the public.

And so, an exhibition was born — a collection of 73 works by 35 artists, including loans from the Guggenheim Museum, the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Brooklyn Museum, that reintroduce an era that was misunderstood and, sometimes, negatively criticized as being too traditional when, in fact, these artists were and continue to be trailblazers, Sultan said.

[caption id="attachment_67302" align="alignleft" width="430"] Audrey Flack (American, born 1931)

Audrey Flack (American, born 1931)

Wheel of Fortune, 1977–1978 Acrylic and oil on canvas 96 x 96 Parrish Art Museum. Gift of Louis K. and Susan P. Meisel,[/caption]

“These watercolors were so beautiful and so unexpected, because even though I know a lot about photorealism, I did not really know about these works,” she said. “With the gift of the two paintings and the introduction of the watercolors, we started talking about photorealism and its place in the world, and how it’s much more highly regarded in Europe than it is here. There have been a lot of exhibitions on this topic there, but only a few in the United States.”

Like many periods in art history, photorealism rode in on the coat tails of a major movement — first abstract expressionism, and then pop art. The three periods unfolded visibly and aggressively, Sultan said, and there was a great misinterpretation of what the photorealists were actually doing.

“Because the topics of the photorealists were just what you see everyday, maybe the critics of the time were thinking more along the lines of the Andy Warhols and Mel Ramoses and Roy Lichtensteins of this world, and missed out on what was intriguing and important about this way of working,” she said of photorealism. “This is one of the reasons that I started working on this project. The more I looked at the paintings, the more intrigued I got, and the more it came back to Chuck Close.”

When looking at a Chuck Close portrait from afar, it coalesces into a picture—even those created from squares of abstract gestures, Sultan said. The same can be said of the photorealists, she noted.

“If you’re standing back, a photorealist painting looks like it looks like a photograph,” she said. “When you go up close, you see that many of the gestures that make up the picture are far more expressive than you could have imagined. I’m fascinated by what your mind and eye does when it receives information in a certain way.”

“From Lens to Eye to Hand: Photorealism 1969 to Today” will open on Sunday, August 6, at the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill. The exhibition will remain on view through January 21. For more information, call (631) 283-2118, or visit parrishart.org.