They gathered on the dock: three archeologists, two college students, three captains, one cook, one engineer, two scuba divers, one able-bodied seaman and Laurie Zaleski, a marine geologist, who had just signed up for the adventure of a lifetime.

She surveyed the team, milling about Port Du Cadiz in the south of Spain, as she considered the expedition ahead of them — a months-long mission to locate a pair of 200-year-old shipwrecks using multibeam sonar, a new application of this particular technology.

The 2004 voyage was among the first of its kind. And they were sailing, quite literally, into uncharted waters.

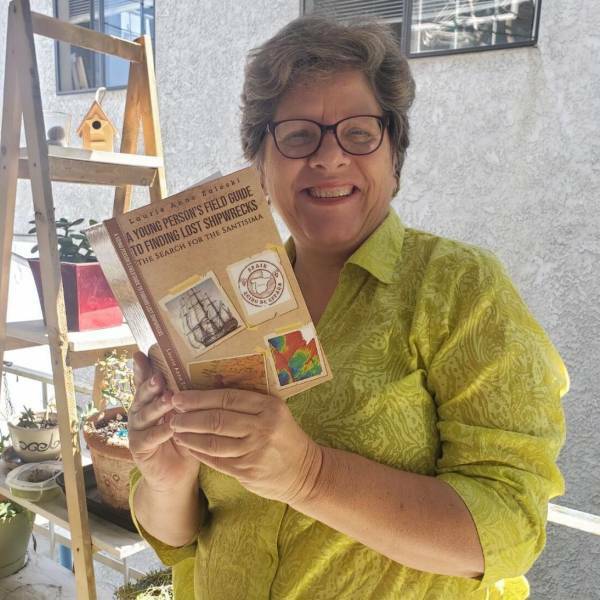

What happened next unfolds in Zaleski’s debut book, “A Young Person’s Field Guide to Finding Lost Shipwrecks,” written for her love of science and what she considers an essential need for children to hold onto their sense of adventure through it.

“If you have a spirit to explore, everyone on that boat was so important — from the cook and the person who swept our floors,” she said from her home in California. “All of those people on the boat served such a fundamental purpose and we couldn’t have done the expedition without every single one of them. It’s not only about being the geologist or being the archeologist, it’s about the expedition and the excitement of it all.”

While Zaleski has now mapped thousands of kilometers by plane, boat and foot, her origin story begins on the East End — Hampton Bays, to be specific, where her father opened Long Island’s first-ever scuba diving shop and fostered her deep admiration for the water and what lurked beneath. Growing up across the street from Shinnecock Bay, Zaleski was digging for clams with her toes by age eight, snorkeling for scallops at Little Pond in Southampton shortly after, and scuba certified by age 13.

After earning a bachelor’s degree in computer science, she decided to pursue her master’s degree at Stony Brook University, this time studying marine and environmental science, with a focus on geological oceanography. “I walked into Stony Brook, I smelled seaweed and dead fish,” she recalled, “and I’m like, ‘I’m home.’”

While surveying Long Island’s south shore using multibeam sonar as part of her studies, Zaleski stumbled across RPM Nautical Foundation, a research and educational organization that does much of its work in the Mediterranean — and happened to be seeking a marine geologist with precisely her expertise for an upcoming nautical archeological expedition looking for shipwrecks off the coast of Spain.

“Two weeks after I got my master’s, I was on my way to Key West, Florida, outfitting two vessels for an expedition,” she said. “Who doesn’t want to go to Spain for the summer and go look for lost shipwrecks? That was pretty much my reaction.”

The two sunken Spanish ships in question, the Santísima Trinidad and the Argonauta, were key players in the Battle of Trafalgar — the final battle between the British and the combined forces of the Spanish and French at Cape Trafalgar on October 21, 1805, during the Napoleonic Wars.

When the French and Spanish surrendered, the Santísima Trinidad was Britain’s biggest prize of the battle, regarded the greatest warship of its time. Despite its four decks, 136 guns and sheer reputation, the English decided to scuttle the Spanish flagship alongside the Argonauta — and just ahead of the battle’s 200th anniversary, it was now Zaleski’s job to find them, aboard the maiden voyage of the 37-meter research vessel, Hercules.

“I landed in Cadiz and go to the boat and everyone was so excited,” she said. “Multibeam had not been used for finding shipwrecks, so we were really pioneers in this. Being a survey manager of such a huge expedition right out of graduating was a lot — between maintaining two boats, making sure all the data was right and, ultimately, trying to make the expedition as successful as it could be.”

The next three months were a whirlwind of science, math and ever-evolving technology, navigating language barriers and learning history, eating tapas and even dancing the flamenco. As for the expedition’s findings themselves, curious young readers will just have to finish the book.

“It was just an amazing expedition, an amazing summer,” Zaleski said. “The takeaway for me was, at the end of the day, people are more alike than they are different. So no matter where you come from, no matter what kind of degree, if you have an adventuring spirit, there’s a spot for you.”

As a scientist, mother and grandmother, the marine geologist is a firm believer in keeping children engaged in math and science — the book, as well as the virtual Zoom lessons she has taught during the COVID-19 pandemic, being a small part of that mission, she said.

“I’m just so grateful that it finally found a port and is not lost at sea,” she said of the book. “Really, why I wrote it, as a female scientist, we lose girls to math and science between fourth and sixth grade. They stop raising their hand, they start thinking they’re not smart. It’s so important to keep girls engaged in math and science.

“Not only do girls need a role model that there are female scientists out there, but boys also need to see that there’s women scientists,” she continued. “And even moreover, science is fun! Who gets to go searching for lost shipwrecks? Scientists do!”