The Second World War, the war to end all wars, ended in 1945, 80 years ago, yet a strange fascination about the Nazis persists, including on eastern Long Island.

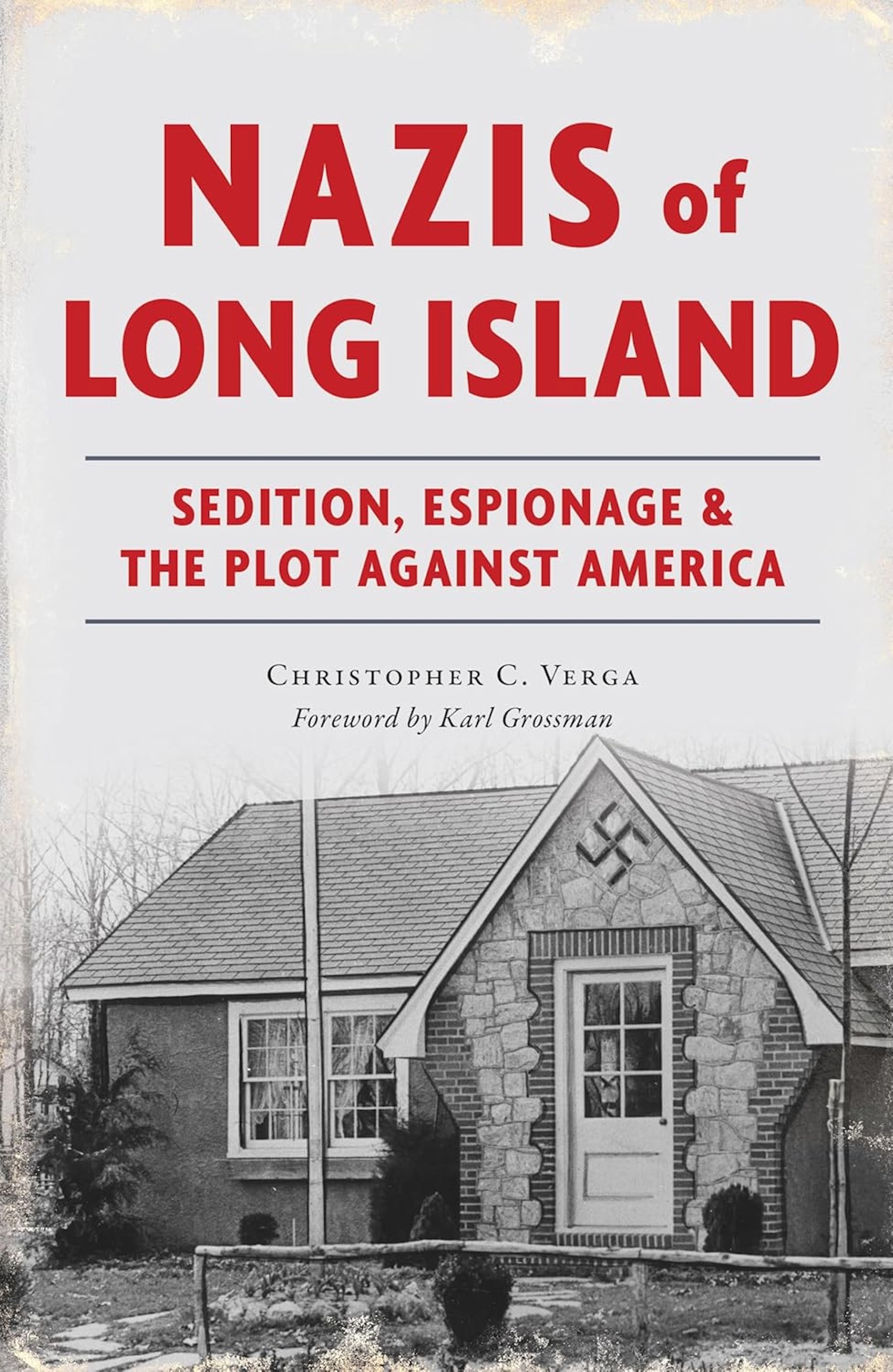

Christopher C. Verga, a Bayshore-based historian and teacher of victimology and the politics of terror, is the author of “Nazis of Long Island, Sedition, Espionage & the Plot Against America” (Arcadia Publishing, 176 pps. $24.99). His book details why the Nazis found Long Island to be a valuable target, serving as a base to help spread their ideology and identify collaborators and supporters among the American public. While Long Island served as a launch pad for spies entering the United States as well as a bustling hub of military production and scientific advancement, a youth camp in Yaphank became a thriving breeding ground for furthering Nazi propaganda during World War II, playing a key role in cultivating the so-called American Nazi.

“It can happen again,” said Verga in a telephone interview when asked about the periodic preoccupation with Nazi ideology around the world. “It started with politicians blaming minorities. Rhetoric led to a surge of paramilitary and other like-minded groups.”

Global leaders also played a role in stoking the flames of hyper nationalism, much of which led to World War II.

“This was the time of the rise of dictators like [Benito] Mussolini, [Josip] Tito and [Joseph] Stalin,” Verga said. “They helped to spread a we’re-the-victims cult.”

The German-American Bund was an extremist organization dedicated to raising support for Nazis among German-Americans. Camp Siegfried in Yaphank became Ground Zero for spreading the ideals of an “American Reich” largely among young people with the ultimate goal of having personnel in position to support a fascist overthrow of Washington.

“It was indoctrination through youth camps,” said Verga.

Bund members swore a loyalty oath to German Chancellor Adolf Hitler. Nationwide, there may have been as many as 25,000 U.S.-based, dues-paying Bund members at its peak during the late 1930s. Membership was strongest in the northern and eastern United States. Many historians describe the Nazi-based activities in Yaphank, as one of the greatest hidden threats to war efforts of the United States. As word spread, however, local opposition groups countered the proliferation of Nazi propaganda in and around New York City and Long Island.

The Nazis’ focus on Long Island went beyond spreading ideology, however, as there were also geographic and technical interests. Hundreds of miles of sparsely guarded coastline provided easy landing spots for spies to infiltrate Long Island’s factories or gain entry to New York City via the Long Island Railroad.

“There was a lot of transition taking place on Long Island during the time leading to the Second World War,” said Verga. “It was changing from an agriculture and tourism neighbor of New York City to an industrial area.”

Jutting eastward from New York City, Long Island was home to numerous defense plants largely engaged in various aspects of the aviation industry, a railroad that dependably shipped food, supplies and troops, plus numerous small ports. On its western tip was the Brooklyn Navy Yard, where literally thousands of boats of all sizes were designed, built and launched as part of the war effort. On the eastern tip, a large government facility was built on Fort Pond Bay in Montauk to test torpedoes to be used against German U-boats. Similarly, the New London, Connecticut submarine base and Plum Island-based Fort Terry, which stood guard at the mouth of Long Island Sound, were each only a few nautical miles away.

On the evening of June 13, 1942, a U.S. Coast Guard seamen on patrol in Amagansett happened upon four suspicious-looking men walking on the beach shortly after midnight in violation of the curfew, claiming to be local fishermen who had run aground. It was actually their U-boat which had run aground on a sandbar about 100 yards off the coast. The men had come ashore in a rubber boat with explosives, cash and tools as well as intentions to travel by Long Island Rail Road to New York City to infiltrate the East Coast and sabotage American war efforts. By June 19 they were each taken into custody. The same railroad also delivered thousands of supporters to the gigantic pro-Nazi rally at Madison Square Garden organized by the German American Bund in 1939, an event many today are surprised to learn actually occurred.

“Aviation was widespread on Long Island. There was a lot of groundbreaking innovation taking place in the labs and factories here,” Verga said. “Sperry developed advanced bomb sights for planes and autopilot technology. Many aviation advances were developed on Long Island. The Nazis wanted access to these secrets.”

The P-47 Thunderbolt, nicknamed the “Jug” was a workhorse World War II fighter plane produced by Farmingdale-based Republic Aviation from 1941 through 1945 and ironically was partially designed by Russian refugee-scientists. The Thunderbolt introduced the famous “bubble” canopy as well as “water injection” for increased engine power. Later versions featured a “dorsal fin” for better stability at high altitudes. Technical advancements such as these helped win the war and many of them were created in part or in full on Long Island. Other companies like Columbia Aircraft and Grumman also had a large presence on Long Island; each contributed technical advancements. Grumman produced several Navy fighters, such as the F4F Wildcat and F6F Hellcat, as well as the TBF Avenger torpedo bomber. Columbia, based in Valley Stream, produced the J2F-6 Duck, an amphibious biplane for the Navy.

Mass production, however, required its own “army” of skilled workers, not all of whom were thoroughly vetted.

“They needed a lot of people and it was impossible to thoroughly investigate each one,” Verga said. “Some spies slipped through the cracks. Many also worked as double-agents. It’s hard to estimate how much damage Nazi espionage caused, but spying cost U.S. lives and most spy rings consisted of Bund members.”

On January 3, 1944, the USS Turner, a battleship built in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, suffered a series of mysterious, internal explosions in its ammunitions storage area and sank off Ambrose Light near Rockaway Point, close to New York Harbor. Rescuers pulled 153 sailors from the freezing waters while 139 of the 292-man crew were declared “missing in action.” The tragedy received limited media coverage due to government censorship. In January 1942, a Nazi U-boat sank the British supply tanker Coimra 60 miles off Montauk Point, killing 36. The ship, which was carrying lubricating oil, had departed from Bayonne, New Jersey and was heading for Halifax, Nova Scotia.

While the U-boat terror across the Atlantic was real, crews needed information to know when targets would be available and what type of cargo they would be carrying. U-boats sank hundreds of ships off the East Coast, more than 200 by 1945.

“Things like maps, port timetables and shipping information were very valuable,” Verga said. “During blackout drills, Nazi crews could see U.S. landmarks. Events like the sinking of the Turner, so close to New York City, did more than kill men and destroy material. It hurt morale, made people fearful.”

In his book, Verga also spends considerable time discussing how quickly Nazi infiltrators mastered the U.S. media in order to sway public opinion to their cause. While rallygoers were often met by hostile crowds in New York City as news of their movement spread, the amount of support such groups received from sympathetic organizations that turned a blind eye to their atrocious activities is alarming.