The air around the Parrish Art Museum and its grand entryway hung dewy and thick last Saturday evening as the guests made their way to the doors.

Once inside, some grabbed wine or champagne, but most walked determinedly and empty-handed into the Lichtenstein Theater, vying for a seat up front to hear co-curators Terrie Sultan and Colin Westerbeck discuss “Chuck Close Photographs,” the Water Mill museum’s new exhibit—these 100 or so in attendance being the first to see it.

Then, there he was. A woman to his right inhaled sharply. And everyone stopped talking.

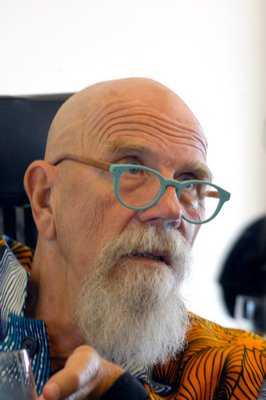

Audience members who were still standing parted for his wheelchair. Chuck Close—wearing a brightly colored, African-patterned, matching pant-and-shirt ensemble designed by his wife, Sienna Shields—divided the sea of guests. His left hand rested limp in his lap, his expression solemn, his eyes staring straight ahead. His overall stillness belied the life found in his artwork.

It was a befitting entrance for Mr. Close, considered to be among the greatest American contemporary artists. But just as Mr. Close, in his work, “loves it when things go wrong,” according to Mr. Westerbeck, one thing was certainly askew that night.

Mr. Close had laryngitis.

And so, the captive audience listened to Ms. Sultan’s and Mr. Westerbeck’s expertise during the preview last weekend for members and guests, including the likes of artists Alice Aycock, Keith Sonnier, John Torreano, Carol Hunt, Laurie Lambrecht, Mary Heilmann and Dan Rizzie.

It is the first comprehensive survey of Mr. Close’s photographic work, featuring 90 images from 1964 to present, including his iconic “Self Portrait/Composite/Nine Parts” and monumental 102-inch-by-208-inch nudes, strategically paired with flowers.

The nudes seem clinical, while the flowers are more erotic in many ways, Ms. Sultan, director of the Parrish, pointed out. “Chuck looks at a flower the way a bee looks at a flower,” she said.

The exhibit explores the full range of his work, from early black-and-white maquettes and intimate daguerreotypes to tapestries and large-scale Polaroid captures, a breadth that screams reinvention.

“One thing about why this is so special,” Ms. Sultan explained, “is that audiences and museums almost never have an opportunity to see the process, to go into the artist’s head. It’s a gift to see the expression. But Chuck is like the bad magician who will tell you how the trick is done.

“And even after we know,” she said, “it’s still magic.”

Born in 1940 in Monroe, Washington, Mr. Close received a bachelor’s degree in 1962 from the University of Washington in Seattle, after two years at Everett Community College from 1958 to 1960, followed by a master’s from Yale University two years later.

“By the time I was 5 years old, I knew I wanted to be an artist—and even that I wanted to be a painter,” Mr. Close explained during a later interview. “When I was 6 or 7, I asked my parents for real paints, and they bought for me the ‘Genuine Weber Oil Color Set’ from a Sears catalogue. My father, who was an inventor and very skilled at making things, made an easel for me.

“When I was in school at Everett Junior College, I discovered the work of Willem de Kooning,” he continued. “I was impressed by the way de Kooning was able to mix figurative elements into Abstract Expressionism. That was a big inspiration to me.”

In 1958, Mr. Close began experimenting with portraiture—first, on himself, he said, while studying at Everett. It was, perhaps, a counterintuitive choice for someone who suffers from prosopagnosia, also known as face blindness, in which he is unable to recognize someone’s likeness. He photographs heads as neutral subjects, Ms. Sultan explained, without interpreting each personality.

“I have always been one to challenge the limits and boundaries of any medium,” Mr. Close said. “I like to push against conventional wisdom of what can and can’t be done.”

The extraordinary facial expressions he pulls out of his subjects are the result of fearless proximity and a bright flash, Mr. Westerbeck said. “Subjects shut their eyes sometimes in response,” he said. “I remember once smelling singed hair.”

Three decades into melding photography with painting, Mr. Close faced a setback when one of his spinal arteries collapsed suddenly. But he continued to work, painting with a brush strapped to his wrist with tape, creating large portraits in low-resolution grid squares.

“Chuck loves difficulty,” Mr. Westerbeck said. “Any medium in which you make mistakes and everything goes wrong, he gets excited.”

As guests circulated through Mr. Close’s vast exhibit, they often stepped back, only to take another step forward, and back again. “It’s the job of the artist to get people to slow down and really look,” the artist explained. “Whatever systems or processes I have developed over time is my way of communicating to a viewer and getting them to pay attention.”

Ms. Heilmann first met Mr. Close at Yale, she recalled, surveying the hanging portraits—Hillary Clinton, Alec Baldwin and Brad Pitt, to name a few, as well as friends of the artist.

“What it is, for me, are just floods of memory coming through with all these people. I know a lot of them,” she said. “And the craftsmanship of the photography and the conceptual way he is dealing with imagery! I’ll be back to spend more time thinking about it.”

“What Mary just said made me think of something,” Mr. Rizzie, who was standing nearby, added. “Even though I wasn’t living in New York at a time where a lot of these pictures were taken, I was spending a lot of time downtown, and all the faces, all the characters, they look familiar.

“I met Chuck when I was student at SMU in Dallas,” he continued. “We went to his studio, and he was painting these huge paintings with just a little bit of paint—black and white. I haven’t seen the whole show yet, and what I have seen is fantastic. I can’t wait to come back.”

“Chuck Close Photographs” will remain on view through July 26 at the Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill. For more information, call (631) 283-2118, or visit parrishart.org.