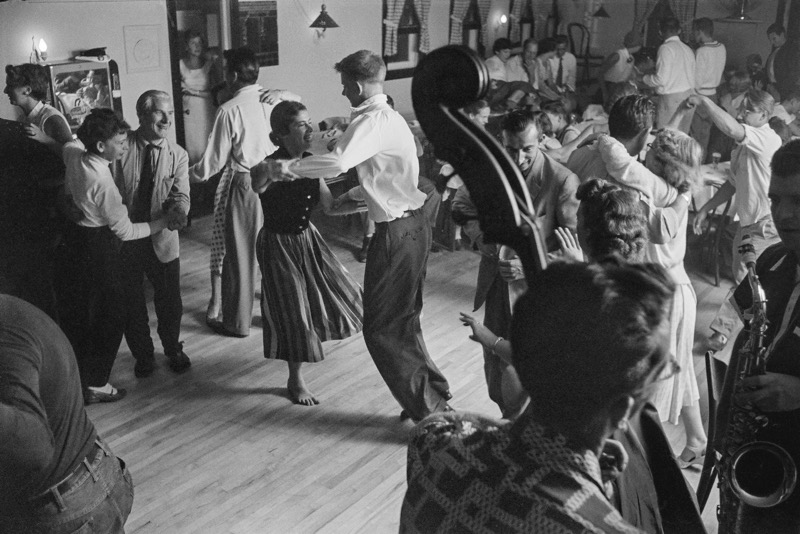

[caption id="attachment_63612" align="alignnone" width="800"] "An East Hampton Dance Party," taken in 1953. Willem de Kooning is dancing, at left, and Leo Castelli's daughter is dancing center. Tony Vaccaro photo[/caption]

"An East Hampton Dance Party," taken in 1953. Willem de Kooning is dancing, at left, and Leo Castelli's daughter is dancing center. Tony Vaccaro photo[/caption]

By Michelle Trauring

“Photography can take us to a place as if you had never left it.” — Tony Vaccaro

Seated at the desk of his Long Island City studio, Tony Vaccaro surveys the room. Familiar faces stare back at him. Faces who were his friends. Faces he photographed.

They belong to Willem and Elaine de Kooning, Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner. Larry Rivers, Constantino Nivola, Fairfield Porter and Leo Castelli. The East End artists’ colony whose presence is still felt to this day, but whose likenesses were never developed by the legendary photographer who captured them.

Until now.

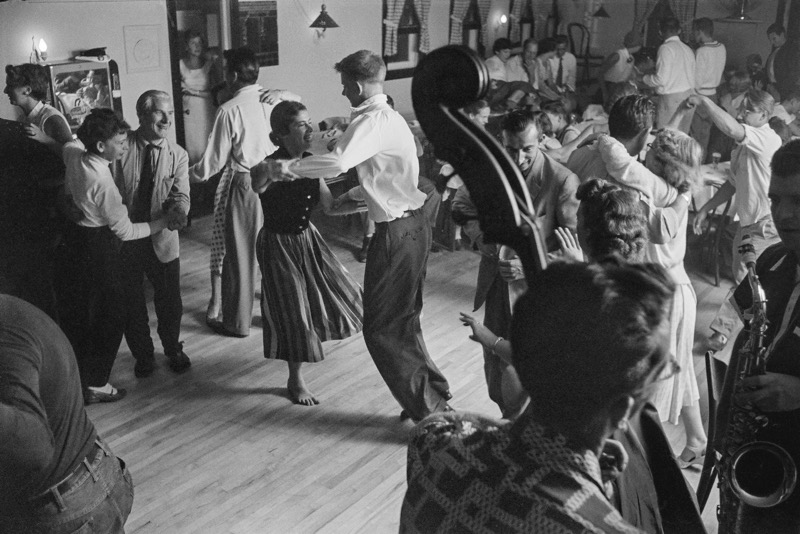

[caption id="attachment_63611" align="alignright" width="454"] Tony Vaccaro inside his studio on his 94th birthday, December 20, 2016. Manolo Salas photo.[/caption]

Tony Vaccaro inside his studio on his 94th birthday, December 20, 2016. Manolo Salas photo.[/caption]

“When you have billions of negatives, many disappear and then, suddenly, they reappear,” a now 94-year-old Mr. Vaccaro mused, the words rolling off his tongue in a thick Italian accent. “There is no mystery. Suddenly a negative’s lost, and it reappears—especially those negatives that I shot in the early days of Pollock and de Kooning. I knew all of those people, you know.”

The never-before-seen photographs — which will be on view starting May 4 at the Pollock-Krasner House & Study Center in Springs — represent a bygone era that will never repeat itself. A time Mr. Vaccaro can recall with remarkable detail and vividness, as he does with most of his early memories.

Born as Michael A. “Tony” Vaccaro on December 20, 1922 in Greensburg, Pennsylvania, his earliest memory is of his mother, waiting for him at the top of the cellar steps. He had been playing with his toys downstairs and started crawling up to her.

“I remember the clothes she was wearing, her dress, and I take one knee over a step at a time and she would say, ‘Come on, come on,’ encouraging me to go up,” he said. “And that’s when, I arrived up, came the embrace, which is what kids love. A mother’s embrace.”

His father was in charge of the city’s road maintenance, a job the mafia had its eye on. When the immigrant family began receiving threatening letters, the patriarch decided to move them back to the motherland—Bonefro, Italy—and he returned to Pennsylvania to sort out matters.

But news of a tragic accident, one a young Mr. Vaccaro witnessed himself, waited for him.

“When he arrived in Greensburg, there was a letter on the table for him. His beloved wife had died, and then my father …”

He trailed off as the phone hit the desk and a sob escaped his throat. “I’m sorry,” he collected himself, putting the phone back to his ear. “I’m sorry, I had no idea. These memories stay with you forever.”

He would be an orphan by age 4, and while his sisters were placed in an orphanage, he was sent to live with his uncle, who put him to work on his farm and beat him black and blue every day, until he returned to the United States in 1939.

While attending high school in New Rochelle, New York, the young boy dreamt of being a sculptor, and showed one of his teachers, Mr. Lewis, a statue bust he had done of Lincoln — which sits on his desk to this day.

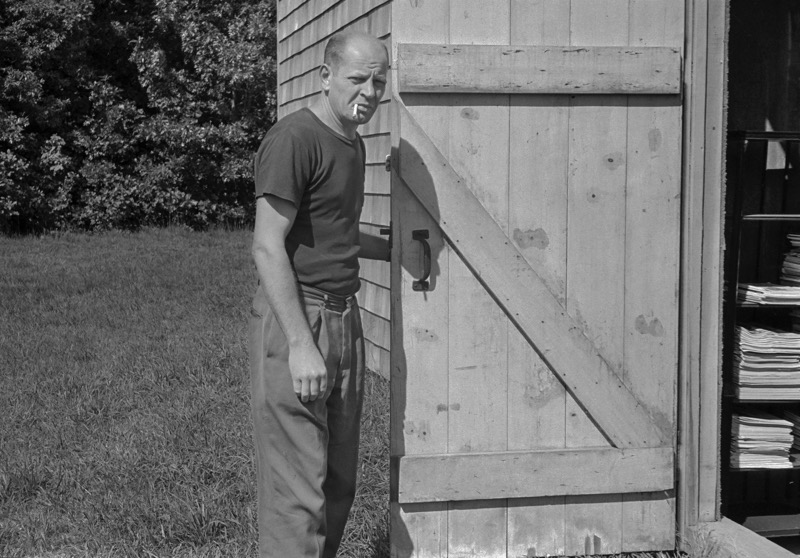

[caption id="attachment_63609" align="alignleft" width="356"] Leo Castelli with Willem de Kooning in back. Vaccaro photo[/caption]

Leo Castelli with Willem de Kooning in back. Vaccaro photo[/caption]

“He said, ‘From what I have seen, Tony, you are a born photographer,’ he told me,” Mr. Vaccaro recalled. “What the basis was for him to say this, I have no idea.”

Cameras had fascinated Mr. Vaccaro from the time his mother took him for his passport portrait, he said, so when he was drafted into the US Army right after graduation, he tried to join the Signal Corps as a World War II photographer.

They said no.

“The Army said he was too young to be a photographer,” according to his daughter-in-law and studio manager, Maria Vaccaro. “He said, ‘I’m not too young to kill and shoot someone, but I’m too young to take a photo?’ He decided to go against the rules and take the photos anyway.”

He shipped off to Europe, a frontline combat infantryman in the 83rd Infantry Division—a gun in one hand, his Argus C3 around his neck, though he sometimes hid it under his jacket. In his 272 days in combat, he snapped more than 8,000 photographs, 25 percent of which have survived.

He got the photos no one else did, and went so far as developing them in Army helmets. He captured all aspects of war, from the mundane logistics of mail delivery and food preparation to unspeakable carnage and firefights that reduce him to tears to this day.

“I was wounded twice, but when I realized I was still alive, I thought it was a miracle,” he said. “For me, to have gone through the war, from Normandy to Berlin, to have seen the blood of Hitler, to have looked at his girlfriend who had just killed herself with a pistol—I didn’t take a picture, I didn’t want those people to be part of history—to have spent that one crazy month in the Hürtgen Forest …”

His voice hitched. “Makes me cry now,” he said. “How many soldiers we lost there, how many friends I lost there. I hope man never has another war.”

Mr. Vaccaro vowed to never return to combat photography, though it was his poignant image, “Death in the Snow” — hanging on his studio wall, just one meter to his right — that caught the attention of Fleur Cowles, editor of Flair magazine.

“She said, ‘Did you take this picture?’ I said, ‘Yes,’ and she said, ‘Can you do fashion in this manner?’ I said, ‘Yes,’” he recalled. “Next thing I know, I have a job. And that’s how I got a job from Fleur Cowles, who out of this one thing made me a pretty great photographer.”

He laughed to himself. “You have to tell the truth, you know. I tell the truth at least to myself.”

[caption id="attachment_63610" align="alignnone" width="800"] Jackson Pollock. Vaccaro photo[/caption]

Jackson Pollock. Vaccaro photo[/caption]

For the next three decades, he would go on to freelance for nearly every major publication, his photography gracing the pages of Life, Venture, Harper’s Bazaar, Town and Country, Quick, and Newsweek, among others. In August 1953, Look magazine asked him to visit East Hampton — specifically, Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner.

“I am looking now at my portrait of Jackson Pollock, where he holds his chin and he’s squeezing and you can see it’s going into his flesh,” he said. “Photography gives us so much of the world that we see. It looks as if it were just yesterday.”

For one month, Mr. Vaccaro rubbed elbows with the East End artist elite, winning them over one by one.

“We know Jackson Pollock was not friendly about being photographed. Willem de Kooning was not happy being photographed while painting, and here we have Tony photographing him,” Ms. Vaccaro said. “I found them about a year ago when I started going through Tony’s archives and opening box after box after box. At first, I didn’t realize who I was looking at.”

Then, it clicked. There was de Kooning dancing, Larry Rivers on the piano, their closest friends smoking, drinking and having a great time. All the while, Mr. Vaccaro was a fly on the wall, occasionally putting his camera down to join in the festivities.

“To have been part of Pollock and de Kooning was something extraordinary. And, in a way, I was proud of it. I still am,” he said. “Right now, I am in my studio and I’m looking at all the pictures of de Kooning, Pollock, all the others. They are in my room and they’re all around me and it was history that we made in those days. History I will never forget.”

“East End Art World, August 1953: Photographs by Tony Vaccaro” will be on view from __, May 4, through July 29 at the Pollock-Krasner House & Study Center in Springs. Hours are from 1 to 5 p.m. on Thursdays through Saturdays. Admission is $5, or free for members, children under age 12, and SUNY/CUNY students, faculty and staff. For more information, call (631) 324-4929, or visit pkhouse.org.