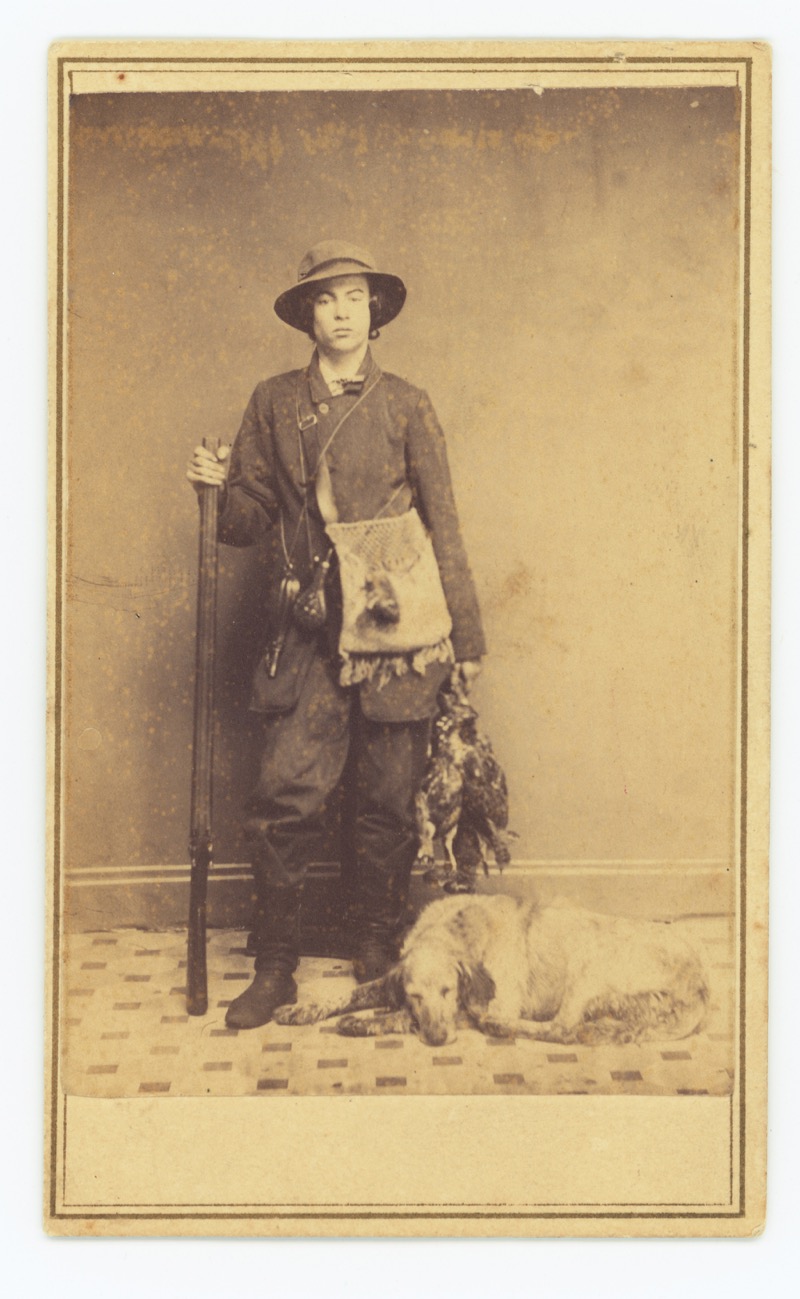

[caption id="attachment_53339" align="alignright" width="408"] Edgar L. Miles Jr., a druggist who worked with his father in one of Sag Harbor's earlier pharmacies, the Botanic Depot on Main Street, in hunting gear.[/caption]

Edgar L. Miles Jr., a druggist who worked with his father in one of Sag Harbor's earlier pharmacies, the Botanic Depot on Main Street, in hunting gear.[/caption]

By Douglas Feiden

There was a widespread belief held by many of the citizens of Sag Harbor in the 19th century that in the hands of Dr. Edgar L. Miles, the roots, bark, herbs, shrubs, stems, spices, weeds, bulbs and tubers that grew in the wilds had wondrous, even magical, powers to restore and rejuvenate and promote healing and wellness.

Now, the Sag Harbor Historical Society is exploring the world in which blackberry was used to treat dysentery, pinkroot to expel worms, Lady’s Slipper to induce sleep without narcotics, hops to treat toothache and dandelions “to correct derangement of the digestive organs and excite the liver and kidneys when languid.”

The life and medical times of Dr. Miles, a so-called “eclectic doctor” who operated his popular village practice from 1845 until three weeks before his death in 1899, is the subject of “Pills, Plants & Poultices,” an exhibit of artifacts, pharmacopoeia, period books, bottles, ads, scalpels and tooth extractors at the Society’s Annie Cooper Boyd House and Museum at 174 Main Street.

At a time when toxic mercury, arsenic, lead, copper, gold, leeches, purgatives and bloodletting were in common use, Dr. Miles was a “medical rebel,” said Deborah Anderson, the society trustee who conceived, curated and directed the exhibition. He rejected the accepted view that disease arose from an “excess of vitality” and could only be defeated by violent means, a regimen known as the “kill or cure” method.

“Nowadays, we know that mercury kills, lead kills and copper kills,” Ms. Anderson said. “These were treatments that did not cure, and in fact, they often killed the patient. And a doctor’s job is always supposed to be, ‘First, do no harm.’”

So along with other like-minded eclectic practitioners, Dr. Miles broke with the “killer cures,” as they were also called, and used plants and herbs — many of which he found right in the village or its surrounding woods, and others that were shipped from afar — to create his own compounds and employ them for medicinal and therapeutic uses.

Operating from the Botanic Depot, an early pharmacy he ran for 54 years from the northeast corner of Main and Washington streets, he found a better way to treat patients by “going back to the old root doctors, who were inspired by Native Americans,” Ms. Anderson said.

[caption id="attachment_53344" align="alignnone" width="800"] An exhibit of the life and artifacts of Dr. Edgar Miles at the Sag Harbor Historical Society's Annie Cooper Boyd House. Michael Heller photo[/caption]

An exhibit of the life and artifacts of Dr. Edgar Miles at the Sag Harbor Historical Society's Annie Cooper Boyd House. Michael Heller photo[/caption]

“Everything that’s old is new again,” she said. “It’s a cycle: The Native Americans understood the use of medicinal plants and herbs. But then came the killer cures. Then Dr. Miles helped to pioneer a movement that said. ‘We want to move away from lead, mercury and arsenic, and go back to the natural herbs and plants that were used by Native Americans.’

“Then cycling forward, we moved toward the use of chemical compounds and pharmaceuticals. And now, there has been a backlash, or a return to alternative or homeopathic medicines, with people again looking at more natural methods of treatment used by Native Americans, which include physical exercise and fresh air. So the cycle keeps going back and forth, back and forth.”

The exhibit also tracks the career of Dr. Miles’ son, Edgar L. Miles Jr., a druggist who worked with his father and had wanted to become a doctor until his eardrums were severely damaged and he lost much of his hearing after he got too close to the fireworks at a Fourth of July picnic in Greenport.

The younger Mr. Miles took over the Botanic Depot, eventually selling the family business in 1908.

And both father and son were prolific advertisers: “Pulmonic Syrup,” one ad proclaims, “lessens the Cough, removes the pain of the chest, gives strength and energy to the system, and has cured many persons who have had every symptom of genuine CONSUMPTION.”

Another ad touts a “Vegetable Composition” known as the “Woman’s Friend” that is “confidently recommended as an excellent compound for Female Weakness and Obstructions” that “warms and purifies the blood, imparting healthy action to the whole system.”

[caption id="attachment_53338" align="alignright" width="268"] Portrait of Dr. Edgar L. Miles, an "eclectic doctor" who practiced in the village from 1845 to 1899 and ran the Botanic Depot, an early pharmacy, on the corner of Main and Washington streets.[/caption]

Portrait of Dr. Edgar L. Miles, an "eclectic doctor" who practiced in the village from 1845 to 1899 and ran the Botanic Depot, an early pharmacy, on the corner of Main and Washington streets.[/caption]

During his 54 years of uninterrupted service in the village, Dr. Miles treated the whalers, fishermen and foreign traders who plied the port, and maritime maladies was one of his specialties.

He apparently used dogwood to treat malaria, boneset for fevers, skunk cabbage for scurvy, cinnamon bark for diarrhea, laudanum for pain and lobelia for syphilis and gonorrhea, according to source material unearthed by the Historical Society that includes a copy of his 1841 medical textbook, which outlines the protocols and practice of a “botanic family physician.”

Fresh from the South Pacific or the Japanese archipelago, whalers would often pay for their herbal treatments with exotic seashells or other barter. Dr. Miles’ wife, Frances, who had journeyed to Sag Harbor with her husband from Connecticut as a 16-year-old child bride, was an avid shell collector, and some of her treasures are on display at the museum.

Of course, in a village with dozens of saloons, thirsty mariners and the occasional rumpot also needed medical attention: “Sweet oil would be most useful in soothing a stomach after a night of strong drink,” according to an exhibit storyboard describing the remedies he provided to suffering sailors.

From 1845 to 1882, Dr. Miles lived and maintained a practice in an old saltbox that is still standing at the corner of Hildreth Street and Brick Kiln Road near Ligonee Brook on Sag Harbor’s western boundary.

“He used a horse and wagon to make house calls, but even then it was far from the village, and sometimes, people would die before he could get there,” Ms. Anderson said.

So Dr. Miles packed up and moved to the corner of Suffolk and Jefferson streets in what is now the Sag Harbor Historic District, closer both to his patients and the Botanic Depot, and lived there with his wife and three of his six children, including Edgar Jr., who never married, until he died 17 years later.

The home at 20 Jefferson Street stayed in the family for four generations, eventually passing to the doctor’s granddaughter, Anita Anderson, who died there in 2005 at the age of 101, and then to her son, Miles Anderson, the great-grandson of Dr. Miles.

Sag Harbor has always been defined in part by its personal family connections. And it just so happens that Miles Anderson is the husband of Deborah Anderson, who directed the exhibition — on her great-grandfather-in-law — with research assistance from, Deanna Lattanzio, Dan Sabloski, Dorothy Zaykowski and society trustees.

In fact, it was in the attic of the Jefferson Street residence where Dr. Miles and his heirs stored most of the artifacts, instruments and other paraphernalia that were used to create the show.

“There was never any room to play in the attic when I was a kid because that was always where all my great-grandfather’s things were stored, along with the Christmas boxes and decorations,” said Miles Anderson.

Those devices came in handy from time to time in the 1950s: More than a century after they were first used, Mr. Anderson recalls, his grandfather would employ one of the implements of Dr. Miles to provide first aid around the house.

“Anytime I would get a wooden splinter when I was a kid, from playing outdoors or in the barn on the property, my grandfather would get out my great-grandfather’s old medical instruments and go to work,” he said.

“There was this tool that had a dark-colored handle made out of either bone or wood and a long stem with a little pointed hook at a right angle at the end of it. He would take the hook and a pair of tweezers and dig out the splinter.”

What happened to that splinter-removal tool? It was actually part of a student dissection kit and is now on display in a glass cabinet at the Annie Cooper Boyd House.

“We’re recycling,” Ms. Anderson said. “It’s a device of many uses.”

[caption id="attachment_53345" align="alignright" width="478"] An exhibit of the life and artifacts of Dr. Edgar Miles at the Sag Harbor Historical Society. Michael Heller photo[/caption]

An exhibit of the life and artifacts of Dr. Edgar Miles at the Sag Harbor Historical Society. Michael Heller photo[/caption]

In 2006, the Andersons sold the house to Bob Weinstein, who painstakingly restored the oldest section on Suffolk Street, which dates to the 1780s, and the newer 1834 Colonial portion facing Jefferson Street, as well as the old barn or carriage house. And it was in that accessory structure that the enduring presence of Dr. Miles again asserted itself.

In the eaves of the carriage house in 2007, Mr. Weinstein found 27 little glass medicine bottles in a cardboard box that appeared to come straight from the manufacturer. Embossed on the bottles, which were sea-blue and translucent, were the words “E. Miles” and “Sag Harbor.”

“They honored the history of the house,” said Mr. Weinstein, who has them proudly on display in the master bathroom.

The exhibit was in the works for at least a year, said Jack Youngs, co-president of the Historical Society.

“Dr. Miles was way, way ahead of his time,” he said. “Doctors were still bloodletting people back then, and here he was in Sag Harbor, using information and methods that the Indians used to help patients with their ailments.”

“Pills, Plants & Poultices: The History of Dr. Edgar L. Miles, Eclectic Doctor, in Sag Harbor” is on display at the Sag Harbor Historical Society’s Annie Cooper Boyd House and Museum at 174 Main Street. The exhibit is free, but donations are suggested. It can be viewed on Saturdays and Sundays, from 1 p.m. to 4 p.m., and by appointment, through mid-October.