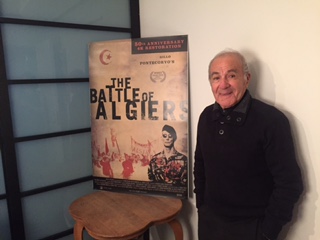

[caption id="attachment_56612" align="alignnone" width="320"] Saadi Yacef. Danny Peary photo.[/caption]

Saadi Yacef. Danny Peary photo.[/caption]

By Danny Peary

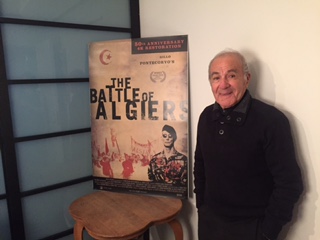

[caption id="attachment_56613" align="alignleft" width="300"] Jaffar was played by and based on Saadi Yacef.[/caption]

Jaffar was played by and based on Saadi Yacef.[/caption]

For 50 years, Italian director Gillo Pontecorvo and, to a lesser degree, screenwriter Franco Solinas have been given full credit for the seminal political thriller, The Battle of Algiers. I admit that I made that same mistake in my writings about the film over time. But now it’s clear that there was an unsung third force behind this remarkable, one-of-a-kind quasi-documentary, Saadi Yacef. Yacef was a producer on the film and played Jaffar (Djafir), the FLN leader in Algiers in the mid-fifties during the brutal Algerian War against France that led to independence in 1962. Significantly, Jaffar was closely based on Yacef, who provided his real-life story to Pontecorvo and Solinas that became the movie. Last week, I posted a small piece about the film to coincide with a 4K restoration print playing at the Film Forum on Houston Street in New York City. (https://sagharborexp.wpengine.com/great-news-battle-algiers-4k-restoration-film-forum/). As a followup, here is an interview (through a translator) that I and two other journalists had the exciting opportunity to do with the charming one-time freedom fighter this week at the Film Forum. I note my questions.

Q: What was your relationship with Gillo Pontecorvo?

Saadi Yasef: I actually paid Pontecorvo and Franco Solinas, who was the scriptwriter, to make the movie. I paid them half in advance and the balance when the film was done. They spent eighteen months in Algiers at my expense and they scouted the locations and really got to know the people. I helped with the small details but Pontecorvo really had the big job to do. He has since died [in 2006], but he came to Algiers not long before then and it was almost like a pilgrimage for him. He wanted to go back to all of the locations where we filmed. And the people loved him. He was a very good director. And he was a good guy.

Q: How much of your memoir was lost in the transfer from book to film?

SY: Sixty percent was lost. As far as the battle of Algiers is concerned, I lived it. And I’ve got three bullets in my thigh to prove it. I was the chief of Algiers, so I knew 100% of what was happening. Nothing in the film did not happen--I experienced it—but for me there are a lot of gaps in the story. Pontecorvo argued a lot about the details. He did a good job but he’d say, for example, “The guns were shot that way,” and I’d say, “No, they were shot this way.” He’d say, “The bombs were built that way,” and I’d say, “No, we built the bombs this way.” He’d argue that he wanted to show what was best cinematically but I’d say that’s not how it really was. I did double the size of the crowds in the demonstrations, but I helped the movie show the reality of what happened. I actually went to the local hospital and gathered all the children who were missing an arm or leg and brought them to the set to be used as extras. The house that the French blow up [with Ali La Pointe and Jaffar’s nephew and a daughter inside] in the film really was blown up and those inside died. When we were going to film that scene, I rebuilt the façade and interior of the house just so we could blow it up again. Also in the film, a bomb is set off in a club in the Casbah and it kills seventy-five people. We rebuilt that club in the exact location where it was before it was blown up, so it could be blown up in the movie. Pontecorvo didn’t want to do it, but I did so we could show exactly what happened.

Danny Peary: Why did the rise against the French happen in the 1950s and not earlier or later?

SY: There was a political party that existed for about thirty years in Algeria. It was an organization that was in place at the time. Algeria had been promised that it would be rewarded in some way, perhaps with independence, because it assisted France during the Second World War, but it didn’t happen. So the time came for the people to make a choice and I was among a small group that decided it was time to declare war against France. At the time the French empire had become very weak so we thought this was the appropriate time to take action against it. The French had a consistent record of trying to take over places and failing. Over the years, they were in Madagascar and failed. And there were failures in Tunisia and Morocco. Vietnam ultimately failed. Basically it was an empire that was trying to remain an empire but was failing and after one hundred and thirty two years of colonization of Algeria we decided this was our time to move. So we did. I was in control of Algiers—that was my area of responsibility. You have to understand that what’s called “our period of terrorism” was only a span of about ten years. At various places, there were explosions and we began to take over certain places. There were 400,000 foreigners that had been put in Algeria to help populate it for France, so we had those people to deal with, too. Here you had a colony that didn’t want to be a colony anymore. We had a handful of people to start but then people began to join us. Old people, young people, women, all of these people joined us because they realized it was the time to do it. It’s almost like a war horse. It’s something that’s very quiet and calm until something incites it into taking action. I think this is a lesson that could be taught to world leaders, this idea of a war horse because if it is calm and the people are calm everything will be fine. But once the war horse begins to get aroused warlike behavior will follow. A few years ago I was here at a conference and I was speaking to a gentleman who may have been a professor. He told me that the Algerian War was won by General De Gaulle. I looked at him and said, “The fact that the French couldn’t get out of there fast enough is proof they didn’t win.”

DP: Are you and the other leaders of the National Liberation Front considered heroes in Algeria today?

SY: I have to say that I am the last survivor of that group of people and the Algerians today are not particularly happy because we made the war and they didn’t.

DP: Have you done promotion for The Battle of Algiers in the past?

SY: Over the years I have done different promotions for the film. When the movie just came out, I brought the film here and it was shown in Los Angeles and won the Academy Award as the Best Foreign Film of 1966. Because of that, the film had a strong reputation. I went to a lot of the theaters where it was being shown and I noticed that American audiences really responded to it. They appreciated what the film said and adopted it. So the film got a lot of publicity and the people at CNN knew about the film, and just before the invasion of Iraq, I came to the States and was asked to give my opinion about what the war in Iraq would mean, in general, for the United States. I did give that television interview and tried to indicate to them what was involved and what could be expected.

DP: What did you say?

SY: I was asked to explain why I had made the film in the first place. I did that and explained why I had committed myself to become involved in the struggle for liberation myself and really combat the monster that was France, which at the time was the third most powerful country in the world. The CNN interviewer was trying to draw parallels between the situation in Algeria in the 1950s and what the possible situation might be in Iraq after the invasion. I was told that President Bush had invited some military officers from the Pentagon to watch the film. I said, “I was visited by agents from the FBI and CIA in Algiers, who came to talk to me what was involved, and I told them that it is important to understand that geographically, economically, and even in regard to how the population behaves, Iraq is a very different place than Algeria. Vietnam was not Algeria either. There may be some similarities but you can never compare one with the other.” I told them quite clearly, “If you go into Iraq today, this is the day you will lose the war. Because if it’s done for the reason of there being some weapons of mass destruction or something else, eventually you’re going to face a population of people with knives who ultimately have the potential to humiliate you. So you’ll lose on the very day that you invade.”

Q: I think it’s natural for people today to look at the arguments for a local population to rise up and use torture and engage in terrorist acts against an occupying country. That happened in Algeria, as shown in you movie, and people try to make connections to what they see today. What do you think contemporary audiences across the world can learn from you film?

SY: It’s very difficult because it’s not the same situation. Iraq was incredibly different.

DP: Donald Trump tries to scare Americans into voting for him by constantly speaking about the link between terrorism and Muslims. In the movie, the word terrorism is used and seems acceptable to the characters and filmmakers, but while the word Arab is used the word to describe the Algerian insurrectionists, the word Muslim appears in the screenplay only a couple of times.

SY: We did not consider ourselves to be terrorists. There should be no direct correlation between Islam and terrorism. In Algeria in the last ten years we have fought our own fight against the Islamic fundamentalists. We got rid of them. I’m going to digress. One of the things that is most important now all over the world is and what everybody wants to do is find peace. Let’s look at the United States. It never had a black president before Obama but if it can now accept a black president, I think it is a country that will accept doing things that bring about more peace. That’s not just talking about it, but doing something about it. Human beings have evolved to the point where “the wolf is eating the wolf,” to quote Socrates. Human beings have a lot to be proud of, such as all the inventions in history like electricity and the telephone, but human beings also invented explosives and other things that give them the ability to kill other human beings. This is something unimaginable in nature. If you want to talk about bringing about peace and ending terrorism, you have to stop building and selling weapons.

DP: There are many scenes in the movie that show violence being perpetrated against the occupiers, including civilians. So how important to the movie is a quiet scene in which the most moderate of the four FLN leaders, Franco, tells the most militant, Ali, that while terrorism is a starting point, violence never wins wars or revolutions?

SY: It will never win. It is a very important scene. Franco recognized the ambition to dominate and he understood it, but at the end he doesn’t want to be part of it. He realizes violence was necessary to begin the struggle but was not necessary to maintain it. For example, if you live in New York and I come to your apartment and try to take it away from you, how are you going to get rid of me? Something strong may be necessary to trigger your getting rid of me but what happens next? Franco worries what happens after the war is won.

Q: The Battle of Algiers was a communal effort between Algerians and Italians to make the film in the Casbah. Considering all the changes that have taken place in Algeria, do you think another film about this subject could still be made there, particularly by a foreign director?

SY: Never. I was there and know exactly what happened. They would have to invent everything.

Note: I also want to recommend indie auteur Kelly Reichardt’s poignant Certain Women, which opens at the IFC Center in New York City on Friday after screening at the New York Film Festival. Of the three stories in the movie, one of the quietest films I have ever seen, the one I keep thinking about stars Kristen Stewart and Lily Gladstone.

On Saturday, definitely check out the Investigation Discovery Channel for the broadcast premiere of Deborah S. Esquenazi’s powerful documentary Southwest of Salem: The Story of the San Antonio Four. This Oscar-contender highlights the ongoing injustice that Elizabeth Ramirez, Cassandra Rivera, Kristie Mayhugh, and Anna Vasquez, are still enduring. They are four Latina lesbians wrongfully convicted of gang-raping two little girls in San Antonio, Texas, despite a lack of evidence. The baseless accusations helped garner the support of the Innocence Project.