By Danny Peary

By Danny Peary

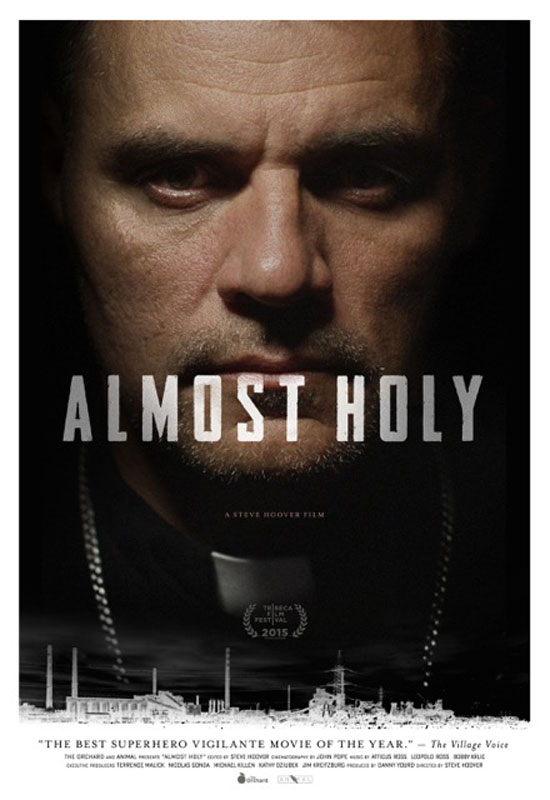

Almost Holy fits my category Movies That Should Play in Sag Harbor. For now Steve Hoover's second feature documentary opens Friday in L.A., and at the Village East Cinema on 12th Street and 2nd Avenue in New York before expanding nationwide. This comes more than a year after its world premiere at the 2015 Tribeca Film Festival under the title Crocodle Gennadiy. Both the new and old titles refer to its controversial protagonist Gennadiy Mokhnenko, a passionate, two-fisted pastor in Ukraine, who since the early 2000s has been forcibly abducting homeless kids, most of whom had became addicted to a lethal cocktail of injected cold medicine and alcohol. He has taken the kids, the film's press notes state, "to his Pilgrim Republic rehabilitation center--the largest organization of its kind in the Soviet Union. Gennadiy's ongoing efforts and unabashedly tough love approach to his city's problems has made him a folk hero for some, and a lawless vigilante to others." From Hoover's Director's Statement: "The journey of this film began in 2012 when some of my coworkers were commissioned to do a promotional video in Ukraine. While in Maripul, they met Gennadiy Mokhnenko and spent a few days with him. After listening to his stories and witnessing his amorphous work, they returned with enthusiasm and proposed doing a feature length non-fiction film on Gennadiy. I wasn't interested in the idea until they shared raw footage with me and further explained some of the context. I was struck by the character of Gennadiy….Gennadiy's former work with drug addled street kids in Ukraine struck a chord with my darker past. Had I been born in Mariupol, Gennadiy would have had me by the collar. I found deeper interest however, not in the kids I empathized with, but in a character I didn't understand….I believe Gennadiy is confounding, so I wasn't comfortable telling people how to think and feel about him. I wanted to show the complicated nature of this character and the world he lives in." I interviewed Steve Hoover in October 2013 about his inspiring debut feature, Blood Brother (https://sagharborexp.wpengine.com/steve-hoover-on-his-inspiring-tribute-to-his-remarkable-friend-blood-brother/), which is about his relationship with his best friend, Rocky Braat, a young man who found his calling taking care of abandoned children with HIV/AIDS at an orphanage in India. Last April, with the film's producer, Danny Yourd, present, I spoke to Hoover again about his new film and the bigger-than-life Gennadiy.

Danny Peary: How well is Gennadiy Mokhnenko known in Ukraine?

Steve Hoover: Gennadiy is marginally famous within different Christian communities in Ukraine. He has been on talk shows on television, so people know who he is in certain places. In the clips we saw, he gets recognized at times on the streets, sometimes by well-functioning adults he actually helped when they were kids. We also saw clips of just random people recognizing him.

DP: Is he considered a threat to anybody?

SH: Now because of the conflict with Russia, and how vocal he is about Ukraine. He’s had death threats from people who stand on a different side and have a different ideology. He is not favored by pro-Russian forces. Also, he creates tension with his religious views. He’s not an Orthodox pastor or priest, and sometimes he’ll put his own personal feelings that some people within religious circles consider spiritual ideals.

DP: Does he preach to the kids he abducts and the people he encounters and always bring God into the conversation? Or if he wasn't wearing his collar, would people even know he is a pastor?

SH: It is a case by case thing. I looked at his conversations to see if the goal of his methods was to bring spirituality to people, and from what I observed it wasn’t. He just had a strong civic duty. However, when he felt it was appropriate, it seemed like he would. I think two of the most telling scenes are the one in the cemetery with his boys, and he’s sort of speculating about life, and the one with him sitting at his desk with his son. He has the opportunity to give a definitive existential answer to his question about death and heaven, but he instead says something vague and without certainty.

DP: How much do you think his troubled childhood as an abused and abandoned kid led to his wanting to help these kids?

SH: It's something. My friend Rocky’s story in Blood Brothers and Gennadiy’s story make me want to explore what makes such people behave like this and make such radical, passionate decisions about helping unfortunate kids. What is the deep psychology that makes them choose to do this? And Gennadiy is aware that his motivations is that he does not want other kids to experience what he did as a child. There’s a really strong, direct connection to that. Especially knowing, on an even more escalated level, what happens to kids and families, when people don't intervene and really intense alcoholism goes unchecked. So I definitely believe his difficult childhood informed a lot of his passion.

DP: Through most of your movie I was thinking that his motives are 100% altruistic, but then he talks about rescuing people from a fire and feeling like a superman. How did you respond to that egotism and admission that he gets personal gratification from helping others?

DY: I looked at him differently seeing him pull kids off the street in the archival footage. I still think he's heroic, but I wrestle with certain things that he does and certain parts of his life. I think everybody wrestles with him. He's complex.

DP: Does that take him down a peg in your view, at all?

DY: I don’t think it takes him down a peg. There are things that he does, walking in a gray area, that I personally would never go into. That’s where I wrestle. But again, we’re cultures away.

DP: In your two movies, you've been extremely tender when it comes to showing a man with young kids. I want to point that out to you. Because of all the news stories we've read about child abuse, many involving the Catholic Church, and what we now see in narrative movies, many directors wouldn't be inclined to include scenes of adult men with kids under their care. Because they would raise red flags. But you include scenes that show men who are kind to kids, and we don't feel we have to be wary of them.

SH: It's provocative idea: a religious figure who abducts kids. Boys mostly, but he’s helped a lot of girls, too. Because we know many terrible things have happened to kids under an adult's supervision, we might think there shouldn't be a relationship between them unless it’s familial. While there should definitely be a sensitivity to it, and people should be cautious, I don’t agree with that. I’m a new father and I cherish my son. I love him more than anything, and I’ve never experienced that before. So when somebody is just trying to help a child, to be family and love and connect with them, I think it’s a beautiful thing to see.

DP: Is he a crusader, a man on a mission or just a man doing his job?

SH: I wouldn't classify it as that. His work is so amorphous and ill-defined, that it's hard to define him. He says there are so many reasons, passions, feelings, that inform his work that there is no one word that sums him up.

DP: Do you feel you know him, and he knows you?

SH: That's a good question. I don’t know if he feels he knows me, but I feel like I know him well through the access he gave us, which was total.

DP: The conflict with Russia stopped him from doing his work with kids. So did it mess up your movie?

SH: It was something unexpected that nobody was anticipating. I wouldn’t say it messed it up, but it had such a big impact on everybody, especially Gennadiy. He’d worked so hard to try to make the country a better place, and then something massive happened outside of his power, that threatened everything that he’d done. He had these sort of shape-shifting adversaries, and the conflict became his greatest adversary. So it definitely had an effect.

DP: Do you think this movie, oddly enough, is also about you, Steve? I ask that because I know from your history with drugs that you identify with the kids Gennadiy helps.

SH: That's a great question, but it’s a hard one to answer. It’s a documentary, it's creative non-fiction, and there were so many decisions that went into finding and shaping the story. I think it is impossible to say that I was completely disconnected, but I mostly was interested in Gennadiy and his conversations and his world, and how that informed who he was.

DP: You were actually a major character in your first documentary, Blood Brother, which dealt a lot with your relationship with Rocky. This movie is different, but It seems like there was a catharsis when making the movie, and you came out the other side a different you.

SH: It was more of a subconscious thing--sometimes I feel I edit stream-of-consciousness, but I do a lot of processing after that--it was never an intentional thing. I was not intentionally telling any story about myself through this film. Watching Gennadiy at work, I can’t relate to it. He’s doing things I’ll never fully understand or emotionally connect to.

DP: Maybe my question should be: did this become, despite being a project brought to you, a really personal film? You spent a lot of time on it, and though you're not in the film you yourself are evolving through the film.

SH: I do think our whole team grew in some way.

[Producer DannyYourd: Steve and I had been working together twelve, thirteen years now and even through our previous films and efforts, we always came out of it somewhat changed. The experiences themselves lent themselves to our possibly looking at life a little bit differently. We entered an environment that was strange and different, and we had a huge separation between language and culture and we just threw ourselves in it as a team of five people. So coming out of that and the experiences that we faced, I think we all changed, and then dealt with stuff throughout the post-production process that changes us as well.]

SH: I didn’t consider making this movie a job. This story fell in my lap, we weren’t commissioned to do it, it was something I connected with. I was just fascinated by Gennadiy. There definitely is a passion in any project I do, but it’s a really fascinating question about whether I tell my own story--it’s something that I could look for in the subtext of my plots, and my films. But I think on every project, even if it is creative non-fiction or a documentary, you feel passion about it and put part of yourself into it, so there might be some reflection of that in the movie.

DP: In this movie, you guys are watching this one man, whom you obviously admire. But did you put him in the hero category, or did you think of a definition of what a hero is? This all had to cross your mind as you watched this guy.

SH: I think for me, Gennadiy was just fascinating to watch-- to watch him and to watch people respond to him, including those he had helped or tried to help. He has a magnetic personality. When he walks through a door, the whole room turns to him. Especially in this place where has had a direct impact on children in the streets, or dying addicts. So he has been a hero to a lot of people and he has that kind of aura about him. He’s aware of what he’s done, but as for me, I just wanted to look at him to watch him. I love the idea of people watching the film and answering that question, asking themselves, "How do I see him? As a hero, or am I just totally boggled by him?" There’s a lot to Gennadiy, and I always tell people that the film definitely doesn’t encapsulate everything he’s done. There are many stories he’s told us that couldn’t make it into the film, and there were things we didn’t film. He's just done too much to fit into one film.

The trailer for Almost Holy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t-uBjW9hhxc

I hope you order a copy of my new book, Jackie Robinson in Quotes: http://www.amazon.com/Jackie-Robinson-Quotes-Remarkable-Significant/dp/1624142443/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1463554187&sr=1-1&keywords=jackie+robinson+in+quotes