The Big Duck is a 20-foot-tall by 30-foot-long ferroconcrete building in the shape of a Pekin duck in Flanders, located in the northwest section of the Town of Southampton. It was first conceived by duck farmer Martin Maurer in 1931 as a retail shop for duck eggs and poultry and was initially located in the Upper Mills section of Riverhead.

As conceived, it was both functional and symbolic—an actual location for purchasing duck products, and a locally iconic landmark heralding the rise and strength of Long Island’s burgeoning duck farming industry, which, at its height, included approximately 90 duck farms.

But since that time, with the decline of the duck farming industry, resulting in just one remaining farm—Crescent Duck Farm, founded in 1908 in Aquebogue—the Big Duck’s function has also shifted dramatically. You can no longer buy edible duck products inside the structure, but you can purchase duck memorabilia and learn about the history of Long Island duck farming.

Despite those changes, the notability of the Big Duck endures. It has been a subject of popular and artistic treatment, in cartoons by Saul Steinberg on the cover of the New Yorker, and in comic strips and countless works of art.

Despite its popularity, it narrowly escaped destruction in the late 1980s, due in part, no doubt, to the strong outpouring of support it received from Suffolk County administrators and local politicians, the now defunct Friends for Long Island’s Heritage, as well as members of the local community.

Most white-tablecloth dining establishments around the world have featured “Long Island duckling” on the menu. The Pekin duck, chosen for its quick birth-to-slaughter-weight time, has become inextricably linked to eastern Long Island, despite not being native to the area.

The multimillion-dollar Long Island duck industry was hatched from one drake and three ducks, which were brought to New York from China in 1873. Long Island’s sandy terrain, waterfront properties, temperate climate and proximity to New York City markets made it an optimal environment in which to breed and raise ducks.

After much experimentation with the breed, duck farms crept up all along the shorelines of Long Island, though the greatest concentration was between Eastport and Riverhead. Some of the earliest farms were Hallock’s Atlantic Duck Farm (1858); Wilcox’s Sea Side Ranch, subsequently named Oceanic Duck Farm (1883); Lukert Farm (1894); and Asa Fordham/A.B. Soyars Duck Farm (1902).

Initially, raising ducks was labor-intensive and required many human hands. Duck farmers would raise their own breeding stock and hatch their own eggs. Pekin ducks stood out among other duck breeds available because they were good breeders, usually laying about 150 eggs a year.

Four weeks were needed to hatch an egg, and the first were hatched with “setting hens” until kerosene heated incubators were introduced. The ducklings would be stored in young brooder houses and fed a homemade fattening mixture. Farmers devised a track system with trains that would bring the feed out to the ducklings.

At about six weeks, the ducklings were sent to the waterfront.

During the early years of duck farming, it was widely accepted that breeding ducks experienced increased fertility by swimming and benefited by having access to water for drinking and cleaning their feathers. As a result, most duck farms were located along freshwater streams on the south shore that fed into bays. If the duck yards did not run naturally into a stream, farmers took great pains to dig artificial canals from the stream to the yards so that their birds would have access to clean water.

Killing day for the ducks came after 10 to 12 weeks. After slaughter on site, the ducks were washed and carried to the picking room. Almost all parts of a duck were incorporated into food or other products. Mostly female pickers would pluck around 50 to 100 ducks per day, and then the feathers would be sold. The ducks were packed in vats of ice and sent to restaurants and New York City markets.

John Westerhoff opened a legendary restaurant in Eastport in 1900 that served Long Island duck and was famous for its duck dinners and signature dish of duck with bing cherries and coleslaw. The restaurant later moved to Southampton; it closed several years ago.

Modern innovations were gradually introduced to the duck farming business, such as electric incubators, food pellets, and the Long Island Duck Growers’ Cooperative, founded in 1921. After setting hens, farmers relied on hot water incubators until the first electric incubator was introduced on Long Island in 1928. The electric incubators cut down on the risk of fire and maintained a stable temperature during the hatching period, turning the eggs three times a day to prevent the embryos from sticking to the shells.

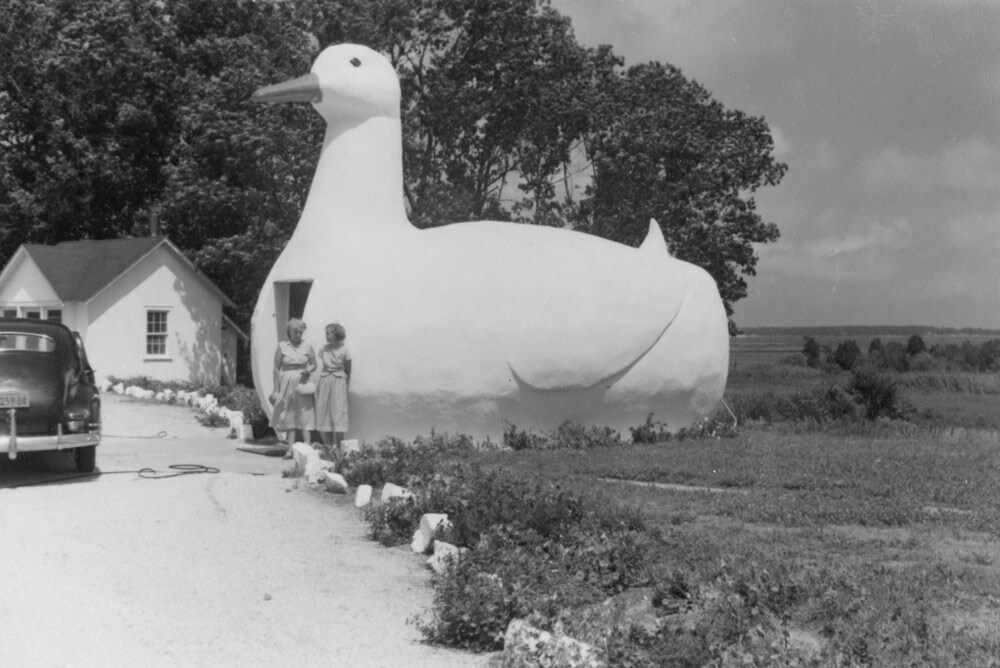

From the 1920s to the 1950s, Long Island duck farms were at the height of business. It was during this time when the Big Duck was erected by duck grower Martin Maurer on the former land of the Pugsley farm in Upper Mills, Riverhead, in 1931.

Maurer was born in 1883 in New Jersey to German immigrants. In the throes of the Great Depression, Maurer and his wife, Jeule, went on a cross-country trip to Los Angeles and, after visiting a coffee shop in the shape of a coffee percolator, he had the idea to build a building in the shape of a duck to sell duck broilers and duck eggs on a farm that he managed on West Main Street (Route 25).

Maurer enlisted the help of local architect George Reeve and theater set designer William Collins, who, along with the assistance of his brother, Samuel, constructed the wooden framework and covered it with wire mesh. Masons Smith and Yeager were hired to do the plasterwork and added four coats of Atlas cement.

When the head was finished, someone got the idea to include Ford Model T taillights, which lit up red at night, for the duck’s eyes.

The Big Duck was completed in June 1931 and, unsurprisingly, did not go unnoticed. Maurer capitalized on all the attention garnered by the Big Duck and marketed it fiercely. He consistently ran newspaper advertisements announcing its opening every March, touting its modern and sanitary facilities, and printed brochures with recipes for duck dinners.

Maurer’s marketing plan worked, and he grew successful enough that he purchased his own farm on Route 24 in Flanders (formerly Naber’s duck farm) in 1936—and took the Big Duck with him in 1936. The Desson family bought the farm from Martin Maurer in 1952. They sold it to Mario and Jean Colombo in 1970.

The Big Duck was most famously canonized in 1972 by postmodern architects Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown in their book “Learning from Las Vegas,” in which they used the term “duck architecture” to classify any building that was a symbol, that took the shape of its function, or “where the architectural systems of space, structure, and program are submerged and distorted by an overall symbolic form.”

After that, any building that took the shape of its function was called a “duck,” no matter the shape.

The height of duck farming on Long Island occurred immediately after World War II: In 1948, 50 percent of the of national duck production was produced by Long Island duck farms. Unfortunately, the continued growth of the farms led to increased pollution of South Shore bays and inlets.

By May 1960, 44 farms formed the Long Island Duck Farmers Cooperative to centralize processing and share costs. In the 1970s, stricter New York State environmental regulations were introduced, specifically focusing on water pollution. As a result of these new policies, Suffolk County Executive H. Lee Dennison vowed to make Suffolk County “a duckless county.”

Farmers were forced to construct wastewater treatment plants and move their ducks inside. Faced with increasing property taxes, and higher costs of grain and labor, rather than invest in updated facilities, many of them chose to sell their valuable real estate to developers and move their farms to the Midwest and Pennsylvania.

By the mid-1960s, the number of duck farms on Long Island dwindled to 48, falling to approximately 27 farms in the late 1970s. By 2009, only three duck farms remained. Chester Massey and Sons in Eastport, the penultimate holdout, closed its doors in 2015, making Crescent Duck Farm in Aquebogue the last duck farm left on Long Island.

President Douglas Corwin credits their longevity with their willingness to evolve and their large investments in wastewater treatment and updated facilities.

The gradual decline in the number of duck farms also threatened the existence of the Big Duck.

The Colombos sold the Big Duck property in 1981 to Kia and Pouran Eshghi, a couple who had emigrated to the United States from Iran. Kia, an accomplished sculptor and painter, hoped to transform the land into an artists’ residence; however, the permits never materialized, and the fate of the Big Duck became uncertain.

The Eshghi’s operated the Big Duck as a poultry shop for two to three years, until they sold the land to a real estate developer in 1986. The same year, at the urging of J. Lance Mallamo, director of Suffolk County Division of Historic Services, and Jerry Kessler, president of Friends for Long Island’s Heritage, the Eshghis donated the Big Duck to Suffolk County to save it from demolition, on the condition that it be moved from the property.

In 1988, the Big Duck was moved a few miles southeast to the 1,000-acre Sears Bellows County Park in the hopes that it would be the crown jewel in a museum of roadside attractions. But the plans were not realized. Once at Sears Bellows, the Big Duck was given a new foundation and restored. It remained there for 19 years, reopening as a gift shop and East End welcome center in 1993.

The Big Duck stood at the entrance of Sears Bellow County Park from 1988 to 2007. During this time, the site of Maurer’s Big Duck Ranch on Route 24 remained undeveloped, and the Town of Southampton purchased it in 2001. There were calls to move the Big Duck back to Flanders.

In 2007, the Big Duck was returned to its original location on Route 24, where it continues to operate as a gift shop and welcome center. The surrounding buildings were restored and a multimedia exhibition of the history of Long Island’s duck industry, curated by David Wilcox and Lisa Dabrowski, was installed in the barn.

Today, the Big Duck is now on the National Register of Historic Places and considered to be one of Suffolk County’s most popular historic sites. It receives approximately 10,000 visitors a year, not including the countless numbers who stop to take a “selfie” in front of the Big Duck.

Similarly, Crescent Duck Farm is still thriving, with the family’s fifth generation of duck growers. A recent Newsday article listed their revenue at $13 million, producing 1 million ducks a year (4 percent of the nation’s duck supply), with plans to build a state-of-the art duck hatchery.

Many other reminders of duck farming on Long Island still persist, including the Long Island Ducks baseball team, Duck Walk Vineyards, and small family-run poultry farms. Like Idaho potatoes and Maine lobsters, duck remains synonymous with Long Island; indeed, one could argue it is the greatest food association that exists to the region.

Despite H. Lee Dennison’s promise to make Suffolk a “duckless county,” with the help of a devoted following and devoted farmers, it will continue to be offered on menus in many restaurants.

Susan Van Scoy, Ph.D., is a professor of art history at St. Joseph’s College, Patchogue, where she specializes in the history of photography. Text and images are excerpted from her book, “The Big Duck and Eastern Long Island’s Duck Farming Industry,” published in March 2019 by Arcadia Publishing.