By Annette Hinkle

They were known as Zwi Migdal.

They were a Jewish mafia of sorts, and from the 1870s until 1939, members of the organization brought an estimated 150,000 to 200,000 young women to South America from Europe and Russia under pretense of a better life. Because they were suffering through pogroms and poverty, families were often more than happy to send their daughters across the sea with nice Jewish men who had made it big in the new world and came touting promises of marriage or a good job.

But once the deal was sealed and the ships set sail, the truth of the women’s situation became painfully clear — they were bound for a new country and a life of sex servitude, forced into prostitution.

In her novel “The Third Daughter” (HarperCollins Publishing), Bridgehampton author Talia Carner uses historical details from the period 1892 to 1910 to tell the story of her fictional 14-year-old protagonist, Batya, one of those young women brought to Buenos Aires by Zwi Migdal, which operated legally as a mutual-aid union of Jewish traffickers.

On Tuesday, July 7, Carner will take part in a Zoom presentation offered by John Jermain Memorial Library to discuss the book. In a recent phone interview, Carner explained that her initial inspiration for “The Third Daughter” came from a short story by Sholem Aleichem, the popular Yiddish storyteller whose tales of Tevye the Dairyman and his daughters who marry against his wishes were the basis of the musical “Fiddler on the Roof.”

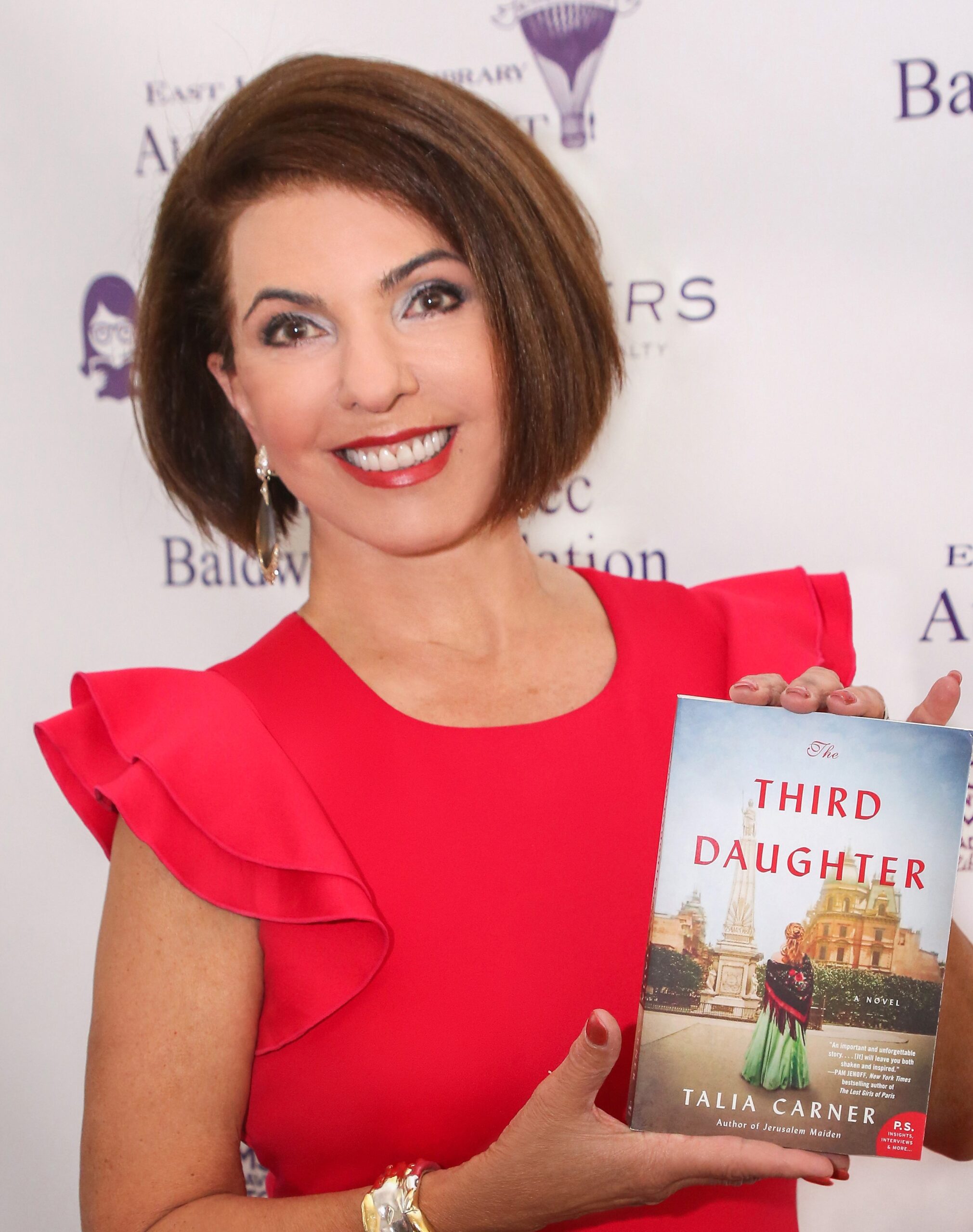

[caption id="attachment_101743" align="aligncenter" width="474"] Talia Carner at the East Hampton Library's 15th Annual Authors Night Benefit, on August 10, 2019 in Amagansett. (Photo by Sonia Moskowitz/Getty Images)[/caption]

Talia Carner at the East Hampton Library's 15th Annual Authors Night Benefit, on August 10, 2019 in Amagansett. (Photo by Sonia Moskowitz/Getty Images)[/caption]

“In 2015, I went to see Fiddler on the Roof again — in my life, I’d seen quite a lot of dramatic representations of Tevye,” Carner explained. “I grew up in Israel and I know Tevye had seven daughters. In Fiddler, they only show the three daughters.”

It turns out that Aleichem had written hundreds of stories about life in the Russian shtetl in the late 19th century, and she ordered a collection of his writings titled “Tevye the Dairyman and the Railroad Stories,” which includes Aleichem’s 1909 story, “The Man From Buenos Aires.”

“The railroad stories are constructed in a way that the author is on a train in Russia and characters come on and tell him stories,” explained Carner. “Unlike Tevye, who is a warm guy who loved his wife and daughters and was a philosopher giving both the questions and answers, the man from Buenos Aires gave me chills.

“He is a sleazy character who is a chatterbox bragging about his business, success and money,” she continued. “He says he has an eye for merchandise and a keen smell, but doesn’t answer what his merchandise is.

“I knew it had something to do with prostitutes and pimps,” she added.

Since 1995, when Carner attended the World Conference on Women in Beijing, she has been interested in working for causes to help end the subjugation of women in all forms. A former adjunct professor at the Long Island University School of Management and a marketing consultant, Carner is an honorary board member of several anti-domestic violence and child abuse intervention organizations. Her focus of concern and her writings have encompassed a range of issues affecting women and girls — from the use of rape during wartime, to clitorectomies imposed on women in Sub Saharan Africa, the burning of brides in India, or the killing of baby girls in China.

“The use of rape as a tool of war to break a woman’s heart and her family’s also tears the fabric of the whole community and breaks the national spirit,” she said. “Back in New York, I started to attend NGO meetings of organizations affiliated with the United Nations and found myself interested in the issue of sex trafficking, never thinking I would one day write about it.

“I’m a feminist,” she added. “But I’m a soldier rather than a general. I need to write novels.”

Coincidentally, back in 2007, long before she read Aleichem’s railroad stories, Carner had occasion to visit Buenos Aires when she and her husband, Ron Carner, who served on the board of Maccabi USA at the time, traveled there for three weeks for the Maccabi Games (often referred to as the Jewish Olympics). While she was there, Carner visited the new AMIA (Asociación Mutual Israelita Argentina), a center that houses Buenos Aires’s Jewish organizations and had been built to replace the AMIA building that was destroyed in 1994 in a suicide bomb attack that killed 85 people.

While visiting the AMIA, Carner made her way to the library where she talked to the librarian.

“I don’t speak Spanish, so we spoke in English and after we talked about the archives, I asked her, ‘What’s the story of prostitutes here?’” recalled Carner. “She suddenly forgot her English. I realized I had stumbled upon something unpleasant and I left it alone.

“But now in 2015, I’m reading ‘The Man From Buenos Aires,’ and knew what he was talking about,” she added.

Carner began researching the topic, and soon learned that Zwi Migdal operated legally in Brazil and Argentina in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

“Enslavement and prostitution was legal. Once these women were captured, they became the property of the brothel and were owned by the brothels,” she said. “Until the age of 21, they were owned by women, and then they were owned by men. They never got freedom.”

And they likely never saw their families again. Many of these young women committed suicide as a way to escape their fate.

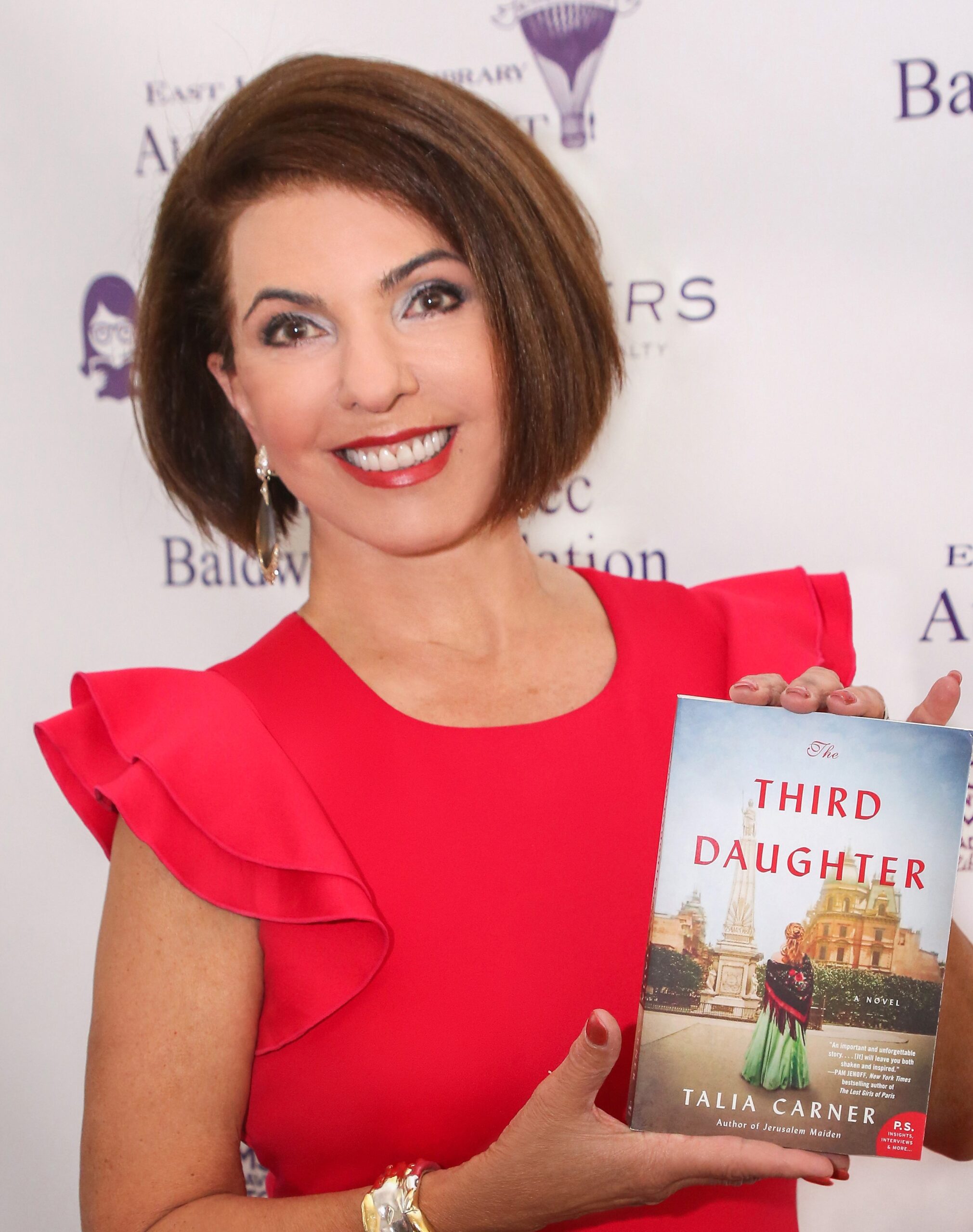

[caption id="attachment_101745" align="aligncenter" width="600"] Screenshot from a 1925 silent film called "Jewish Luck," directed by Alexis Granowsky. The film stars Sholem Aleichem's character, Menakhem Mendl, who is scheming a quick-money venture of exporting "brides" to America. The photo is a dramatization of that man's dream.[/caption]

Screenshot from a 1925 silent film called "Jewish Luck," directed by Alexis Granowsky. The film stars Sholem Aleichem's character, Menakhem Mendl, who is scheming a quick-money venture of exporting "brides" to America. The photo is a dramatization of that man's dream.[/caption]

“I started reading books and dissertations and continued to read about it. I found that at one time, there were 30,000 women employed, from South America and Beijing, to the Lower East Side,” Carner explained. “In my statistician’s head, I created a pyramid — over 70 years with a life expectancy that was short, that’s 150,000 Jewish girls and women at least.

“From that point on, I was a goner. I tried not to write about it, but I couldn’t. The voices of these women wouldn’t leave me alone,” said Carner, who also learned that the tango was developed in the brothels and even took a year-long private lesson in order to write about it with authenticity.

In constructing her story, Carner felt it was natural to pick up the tale from where “Fiddler on the Roof” left off. The “Third Daughter” begins with Tevye the dairyman and his wife (named Koppel and Zelda in Carner's book) on the road with Batya and her younger sister, Surale, having been driven from their shtetl with the few possessions they can transport on a handcart. Batya’s two older sisters have already defied their parents by marrying outside tradition and have left to start lives of their own.

“That’s when they meet the man from Buenos Aires,” she said. “He’s looking good and well-dressed in an area where Jews are suffering from pogroms and squalor and forbidden from owning property.”

It’s under those circumstances that the stranger offers Batya marriage and a new life in America.

“It’s such a godsend and the hope was one person leaves the country and brings the rest of them along later,” she said. “That’s how the story begins.”

But that’s not where it ends, and Carner explained that the well-dressed man, like the one in her novel, was a Jew who had left the shtetl for South America and came back on expeditions. Because not all Zwi Migdal members were young and handsome, younger men worked throughout Eastern Europe to gather the girls.

[caption id="attachment_101746" align="alignnone" width="10500"] Screenshot from a 1925 silent film called "Jewish Luck," directed by Alexis Granowsky. The film stars Sholem Aleichem's character, Menakhem Mendl, who is scheming a quick-money venture of exporting "brides" to America. The photo is a dramatization of that man's dream.[/caption]

Screenshot from a 1925 silent film called "Jewish Luck," directed by Alexis Granowsky. The film stars Sholem Aleichem's character, Menakhem Mendl, who is scheming a quick-money venture of exporting "brides" to America. The photo is a dramatization of that man's dream.[/caption]

“They would say, ‘You’ll stay with my cousin,’ or they’d bring them to the boat in Odessa,” Carner explained. “He’s supposed to be the groom, but would say, ‘I’m sorry. I have business to attend to. My associate will take you, and I’ll meet you there in three weeks.’”

But of course, the groom would never arrive.

As an organization, Zwi Migdal reached its peak of power in the 1920s. No doubt, it operated so long because the Argentinian government profited greatly from prostitution — in 1920, Carner says a quarter of the state’s revenue was generated by brothels.

But eventually, one federal police commissioner in Buenos Aires, Julio Alsogaray, was motivated to act. He had forged an alliance with other Jews who condemned the traffickers and in 1930, met Raquel Liberman, a native of Poland who had been brought to Argentina seven years earlier and forced into prostitution. Widowed and the mother of two boys, she had tried more than once to start a new life by investing her savings in an antique shop, but Zwi Migdal had repeatedly sent goons to wreck her shop, forcing her back into the brothels.

Liberman’s cooperation led Alsogaray to conduct police raids on Zwi Migdal, whose members quickly began fleeing the country. Public opinion finally turned against them. Though Zwi Migdal was weakened, it continued to operate throughout South America until 1939 — ironically, once Hitler invaded Poland, traveling there to “recruit” was no longer possible.

Though the story of Zwi Migdal is now history, the truth of sex servitude and the subjugation of women through forced prostitution continues unabated. For her part, Carner’s goal is to put a face to the countless victims who never were able to provide a better life for their families.

“I know now why I want to write — to show the humanity of my protagonist,” said Carner. “A girl has been trafficked, and we fall in love with her and get so deeply involved in her dilemmas. I don’t think a single reader can think bad of her — and we understand today’s victims.”

And the librarian in Buenos Aires who suddenly “forgot her English” when Carner asked about the history of prostitution in the city?

“I understand why, if you have a community so badly tainted by it,” she said. “Now, viewing it with my 21st century sensibilities, I see them as victims.”

Talia Carner discusses “The Third Daughter” on Tuesday, July 7, at 4 p.m. in JJML Live, a Zoom event sponsored by the John Jermain Memorial Library in Sag Harbor. Register at johnjermain.org orhttps://us02web.zoom.us/meeting/register/tZEkc-urqDwjHdUaWXXnBjaLpwnNkH86IDUO.