[caption id="attachment_61202" align="alignnone" width="1024"] A fan brought back from Southeast Asia is part of the Southampton Historical Museum's whaling artifact collection. Photos courtesy of the Southampton Historical museum[/caption]

A fan brought back from Southeast Asia is part of the Southampton Historical Museum's whaling artifact collection. Photos courtesy of the Southampton Historical museum[/caption]

By Michelle Trauring

Shoved into the back corner of the Southampton Historical Museum archives lies the remains of a lost era, collecting dust for the last 70 years.

From a 3-inch piece of intricately carved scrimshaw to a boat with 15-foot oars, the massive whaling artifact collection has always fascinated Emma Ballou from afar. This year, she decided it was finally time to get up close.

"We haven't been able to get them out because they're really big—whale bones, harpoons and a lot of artifacts," the curator said of the collection. "The last great exhibit was in the 1950s, and it hasn't been touched since. It's kind of daunting to think about getting them out again. I was like, 'This is it. We're doing it. I've got to get them out of there.'"

For nearly two centuries, one of every two people in Southampton was somehow involved with or touched by the whaling industry—an integral part of the town’s history and a key chapter in its development—and witnessed its rise, height and downfall, according to executive director Tom Edmonds.

When the industry bottomed out in the 1850s—a perfect storm between overfishing and the onset of the Gold Rush—the East End spiraled into a deep depression, only to be saved by rich New Yorkers two decades later.

"Everybody forgot about whaling," Mr. Edmonds said. "It's old here. Whaling started 12,000 years ago with paleo-Indians coming over and settling and looking for big game. And the Shinnecock helped teach the English pioneers in the 1640s how to process whale meat from whales that washed up on the shore. It was an unbelievable gift from heaven—blubber, hide, all this stuff they could use. So whaling, the Shinnecock had been doing offshore before the English got here. It's kind of ancient history."

[caption id="attachment_61204" align="alignright" width="395"] Scrimshaw that's part of the Southampton Whaling Museum's collection of whaling artifacts.[/caption]

Scrimshaw that's part of the Southampton Whaling Museum's collection of whaling artifacts.[/caption]

A full 100 years before Sag Harbor was even on the map, there was Sherverson, founded by John Ogden, the first captain to obtain a patent for commercial offshore whaling in the colonies. Once located at Conscious Point on North Sea Harbor, it was the third largest port in the Northeast―landing him not far behind Boston and Philadelphia—until Sag Harbor supplanted it, with its deeper harbor allowing for larger ships.

This sort of industry—one filled with equal parts excitement and danger—attracted a cast of local characters, who will anchor the first of two whaling exhibits at the museum, "Hunting the Whale: The Rise and Fall of a Southampton Industry.”

"I'm really interested in the day-to-day life of people from different time periods because I think that's how you can most easily relate to somebody," Ms. Ballou said. “But it doesn’t really explain all of the artifacts that will be on display in the Sayre Barn later this spring.”

It is not an easy slice of history to dissect, she noted, despite the whaling industry’s romanticized, nostalgic charm today. In reality, the industry was a perilous one, often keeping men out at sea for years at a time, leaving their families wondering whether they would ever return home.

“It was very much like hero worship a little. Everyone wanted to be a whaler. Every boy, man wanted to be a captain and going on whaling voyages. It was the cool thing to do at that time,” she said. “While they were at sea, it was easier to process the whale on the ship. SO I have this image in my head of this fuel-soaked whale oil everywhere—it was very flammable—and these wooden ships just coated in it. And they would have to process the oil and all these ships would be set on fire all the time.

“And the whaling and hunting itself? It was this brutal, horrible process,” she continued. “The whales would interact with the whalers, they would see them coming and try to kill them, try to stop it from happening. It got very ugly. We’re just going to be very factual about it.”

A typical day at sea was boring and life threatening at the same time, Mr. Edmonds said. Anything could happen, he said, and there were a lot of accidents.

“The whaling ships would have smaller boats, enough for 12 man to oar, and they would go out to chase the whale with one guy throwing a harpoon,” he said. “Sometimes, the guy who threw the harpoon would go into the water with the whale and get dragged. A whale could turn a whole ship upside down and could attack ships—and a lot of men died from that. It was a live-or-die occupation.”

For one such Captain Thomas P. Warren, a particular voyage in the late 1890s was to be his last. He was a young man with a young family, Mr. Edmonds said, and he told them he wanted to go out one final time.

“He brought his whaling ship to the Bering Strait, up by the arctic circle—by this time, it was the only place to find whales," Mr. Edmonds said—and he got caught in an iceberg.

[caption id="attachment_61208" align="alignleft" width="385"] A hand-carved whalebone toothbrush is part of the museum's collection.[/caption]

A hand-carved whalebone toothbrush is part of the museum's collection.[/caption]

“They were moored for five months,, without any way of getting food,” he said. “Men committed suicide. Some of them survived. A U.S. rescue ship came and broke the ice around them to free the ship, and where do you think they decided to go? They wanted to keep whaling. They didn’t want to go home. They wanted to go out and make the money and come home with cash. It didn’t break their spirits. They could have gotten on this U.S. ship to go home, but they decided to stay out and keep whaling, go figure.”

He laughed to himself, and continued, “Men were men, I guess. Stupid but determined. The guy who left his farm, he died. You can imagine his family, everyone knew he was going out for his last time, and he didn’t make it. What a sad story it was, but a colorful story.”

It can be easy to be blinded by the nostalgic, romantic aspects about any chapter of history, Ms. Ballou said, but emphasized that there is often more beneath the surface.

“This was the height of Southampton, of the East End. Every single person knew somebody who had gone on a whaling voyage. This was their way of life. And at that time, it was accepted. At that time, it was the norm,” she said. “It’s like how the South viewed slavery. Obviously, this is not human beings we’re talking about, but even that period is romanticized. That’s just what people do. They’re nostalgic about the past and that’s why it’s important to think about both sides of it.”

“Hunting the Whale: The Rise and Fall of a Southampton Industry” will open on Saturday, March 4, at the Southampton Historical Museum’s Rogers Mansion, and will remain on view until December 30. Admission is $4. The second part of the exhibition will open later this spring inside the Sayre Barn. Tom Edmonds will give the talk, “The Men Who Hunted the Whale: Southampton’s Many Sea Captains” on Thursday, March 9, at 1 p.m. at the Rogers Memorial Library in Southampton. Free admission. Additional events in conjunction with the ongoing exhibit will continue throughout the year. For more information, call (631) 283-2494, or visit southamptonhistoricalmuseum.org.

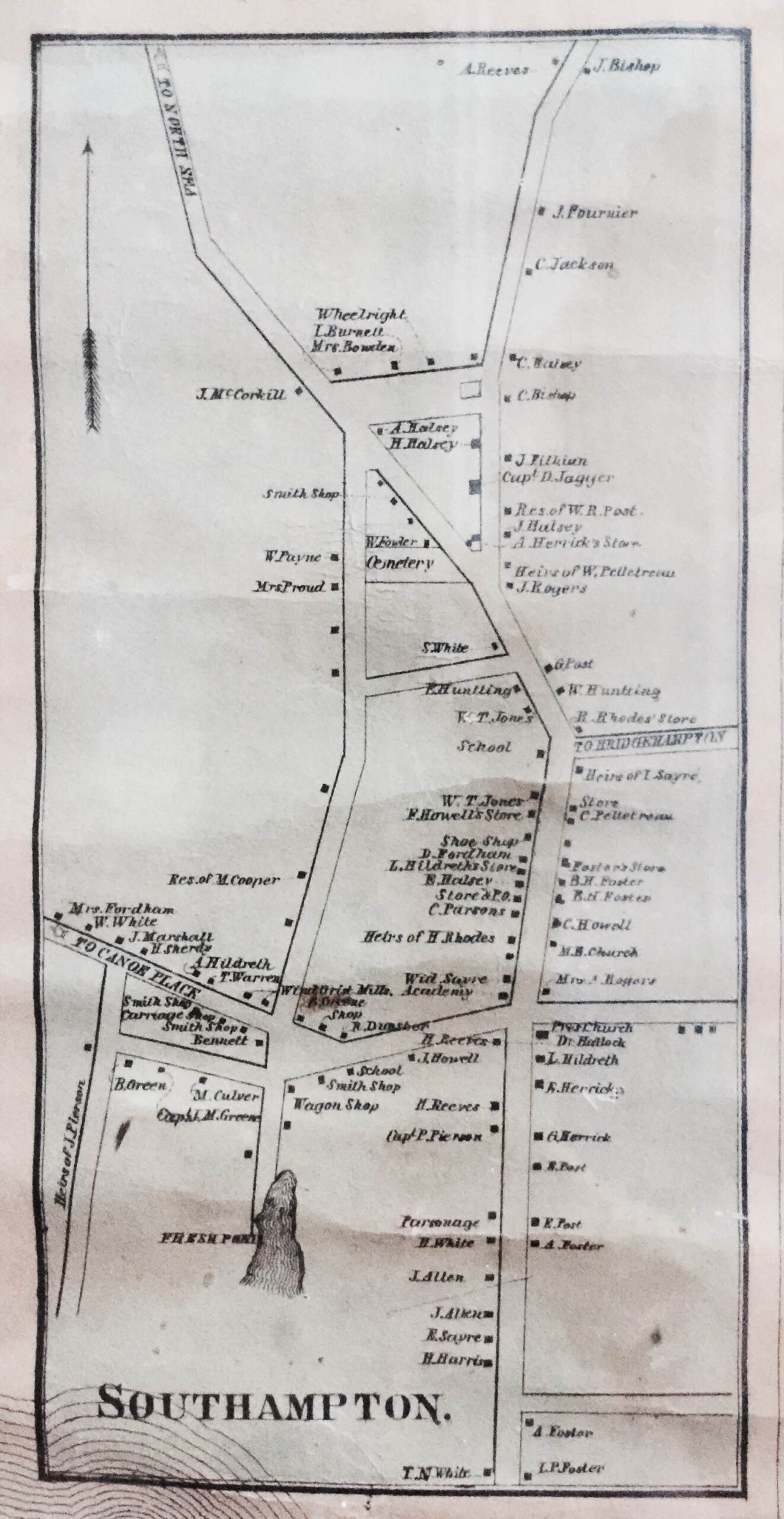

[caption id="attachment_61206" align="alignnone" width="529"] An 1858 map of Southampton Town. See below for key.[/caption]

An 1858 map of Southampton Town. See below for key.[/caption]

KEY - 1858 MAP

1 – Southampton Academy: Erected in 1833 and moved in 1895, the neat, two story building with a bell tower was where three generations received their high school education. Classrooms were on the first floor and a public hall on the second.

2/3 – The Third Public Schoolhouse. Built in 1804, the schoolhouse was cut in half in 1814 and the south half moved to Jobs Lane (3).

4 – Josiah Foster Property – Josiah and his wife Abigail ran an inn in the early and mid-19th century, a stagecoach stop where guests included James Fenimore Cooper and Daniel Webster. The building was subsequently purchased by Samuel Parrish and moved to First Neck Lane.

5 – Captain Howell House – Captain Howell, who married Mary Rogers in 1831, purchased the house on Main Street which dated back to 1688; their son George Rogers Howell (b. 1833), who was raised there, became an esteemed NY State Archivist. Capt. Howell sold the south portion of his property to the Methodist Church in 1843. Later the Howell house was purchased by Richard Post and moved around the corner to 30 Wall Street.

6 – Methodist Episcopal Church – When, in 1843 the Presbyterians vacated their 1707 church, they planned to sell it to Major Samuel Bishop for a barn. There was an outcry over the unsuitability of such a use and the Presbyterians ultimately sold it to the Methodists who had bought property from Charles Howell (5). Historian William Pelletreau reports that Captain Albert Rogers was not pleased by the new location adjacent to his own property and made “some energetic remarks” to that effect.

7 – Wind/Grist Mills (The Old Mill Hill Mill) – Built in 1708 on land thereafter known as Windmill Hill. A real hill at the time, it was later graded and the sand used to fill the streets. At one time there were two windmills but following a severe storm, the damaged mill was moved to Wainscott; the other was eventually purchased by a private party andmoved to Shinnecock Hills where it remains on the SUNY Stony Brook Southampton campus

8 – Sayre House – Built in 1648, it was the home of Captain Thomas Sayre and his descendants. Every timber was of hand-hewn oak; the nails were hand-forged and it had the classic lines of a “saltbox,” two stories in front with a long roof sloping down to one story. In 1911, it was condemned and torn down despite vigorous protests.

9 – First Presbyterian Church of Southampton – The third building to house the Presbyterian congregation, which dates back to 1640, it was built in 1843.

10 – Dunster House and Shop – Richard Dunster arrived in New York City from England with his family in 1842. A machinist by trade, he failed to find work in the city and, with his family, walked the length of the Island, landing in Southampton where he found work as a miller and eventually set up his machinist shop on Jobs Lane.

11 – The Home of Captain J.M. Green - One of the many Green family seamen, he built his house sometime between 1820 and 1840.

12 – Captain William White Home – Captain White was the last owner of the Mill Hill Mill, according to historian Lizbeth White, and he lived “up the Hill” [on Hill Street]. But “when Edward Bennett brought home his bride, the ‘Miller’s ‘ house became their home.

13 – “Uncle” Tom Warren Home – A whaleman, though never a captain, “Uncle” Tom Warren joined the company that sailed aboard the Sabina to the gold fields of California. When his seafaring days were over he returned to Southampton where he was a well-loved village character. He lived to see his son and namesake become a captain and, living on to a ripe old age, eventually to become “Southampton’s oldest resident.”

14 – Merritt and Caroline Culver Farm – The Culvers owned a farm on the corner of Pond Lane and Culver Hill and gave the street its name.

15 – Culver Carriage Shop – When George Culver, Merritt and Caroline’s son, returned from fighting with the Union Army in the Civil War, he became the proprietor of the carriage shop on Hill Street. His ad in the local paper states “George Culver: Carriage and Wagon Builder, Painter and Trimmer.”

16 – E.C. Bennett Practical Horse Shoer – Handily located next door to Culver’s Carriage Shop is E.C. Bennett’s blacksmith shop. (The building is now on the grounds of the Southampton Historical Museum.)

17 – Samuel Rodber Veterinary and Horse Shoer – Rodber was a recognized veterinarian but said to have little interest in animals other than horses. The village depended on horses - saddle horse, farm horses, coach horses, delivery horses – enough to keep several shoers in business.

18 – Home of John Fournier – The Fournier family arrived in America in time to fight in the Revolution when John’s forebear signed his name on his military papers “Francis Fournier, Frenchman.” Of the large family only two remained in Southampton. John Fournier built nearest the (future) railroad station. Arabella Fournier charmed the neighbors with her “quaint eccentricities.”

19 – William R. Post House – William R. Post bought the property on North Main Street, which had belonged to his father-in-law, Captain James Parker, a whaling captain who sailed for the gold fields in 1849 aboard the Sabina and died in California two years later. (His grave is in the North End Burying Ground in the company of his four wives.) Post, very prominent in Southampton where he served at various times as supervisor, Presbyterian Church elder and Sunday School supervisor, built the home, which was widely admired as a mansion in its day and up to the present.

20 – Captain “Harry” Halsey House – Harry Halsey, who had apprenticed in New York as a mason, returned to Long Island and bought a plot fronting North Main Street from Annanias Halsey and built his house. Both his brothers became whaling captains but he farmed and worked at his mason’s trade. His title of “Captain” came to him as a wrecking master. One room in the house was where “Miss Amanda” kept her Dame School. Whenever a whale rally broke the routine, Captain Harry would tear into the schoolroom, grab a big pewter horn that hung on the wall and blast the news”: Whale off shore! All hands on the beach!

21 – Captain William Fowler House – Elizabeth Halsey, sister of Captain Harry Halsey and Captain Jesse Halsey, married Captain William Fowler and settled just north of the North End Burying Ground. A whaler, Fowler also spent several years in California during the gold rush. Three of the Fowlers’ sons went on whaling voyages and never returned. In her sorrow, Elizabeth became the neighborhood mother and was fondly known as “Aunt Libbie.”

22 – Jonathan Fithian House – Jonathan Fithian came to Southampton as a very young man (1818) and taught first in the district school and afterwards at the Academy. He married Abigail, daughter of Thomas Sayre and their home was built on substantial acreage, which was long known as “Fithian’s Lot.” Their five lively daughters, “the Fithian Girls,” made their home a popular social center. Their father was a pillar of the Southampton establishment, serving at various times as Town Clerk, Justice of the Peace and Town Supervisor.

23 – Herrick House – Built by silversmith David Howell in 1750, the house, which was occupied by British officers during the Revolution, later passed to the Pelletreau family. Elias Pelletreau, a merchant, built the store that remained many years attached to the house. Austin Herrick coveted the house but acquired it only after shipping out as a whaler, surviving a shipwreck, and persuading the initially reluctant Mary Jagger to marry him. Captain Austin Herrick made 17 voyages before retiring to keep the store. A man with a strong moral compass, he is said to have walked out of the church when the minister preached a sermon in defense of African slavery.

24 – Cooper Hall – Among the most prominent and prosperous of Southampton’s whaling captains, Captain Mercator Cooper extensively remodeled his father’s 1805 house to create the handsome Greek Revival residence on a hill overlooking the village sometime in the 1840s. Cooper began his seafaring career in 1822 at the age of 19. He rose quickly to captain and made many whaling voyages, the most famous being his voyage on the Manhattan when he achieved fame for being the first American captain to sail into a Japanese harbor.

25 - Captain George G. White House – In 1651, John Jagger was granted a home lot which eventually became the property of the White family. Among the most illustrious of the Whites was Captain George White who shipped as cabin boy with Captain Mercator Cooper at the age of 14 and “followed the sea” for the next 26 years. In 1849 he headed for the gold fields of California where he was modestly successful and, in 1851, he returned to marry Elizabeth Fordham and settle into life as a farmer and a political activist, a forceful voice in defense of residents’ rights to the beach and of the area’s natural resources. His reputation for absolute integrity and his daunting courage, even in old age when he faced raging seas to save shipwrecked crews, were never questioned.

26 – Herrick’s – One of Southampton’s oldest commercial structures, it appears on early maps as “store and post office.” Later references are to “H.F. Herrick store,” “B.F. Herrick,” and “Herrick.” Relatively unaltered since 1858, though its merchandise has evolved, Herrick Hardware remains a vital Main Street business today.

27 – Hildreth’s – Established in 1842 by Lewis Hildreth, the business occupies the original structure, appropriately updated and expanded. When it first opened all of its merchandise came by ship to Sag Harbor and was carted to Southampton by horse and wagon. The inventory was vast and varied with everything from groceries and household products to medicines and harpoons for the whalers in stock.

28 – Captain Edward Sayre House – Captain Sayre’s house, built c. 1836, is the mate to the Presbyterian manse (36) further north on South Main Street. Among Captain Sayre’s whaling voyages was one to the South Atlantic in 1834 aboard the ship Neptune that appears to have been very successful. The pages of the ship’s log (on display) show many of the small images of whales that signal a successful kill.

29 – Rogers Mansion - Captain Albert Rogers (1807-1854) was the creator of this Greek Revival mansion in 1843. Standing on land belonging to the Rogers Family since 1645, Rogers lived in it with his wife Cordelia and their children. The splendor of its architecture and graceful interiors testify to his success during the height of the whaling era. The house was later purchased by Dr. John Nugent who sold it to Samuel Parrish in 1899.

30 – The Post House - The Post family brought its name to the property in 1824. George Post was in residence in 1858 and his daughter, Sarah Elizabeth, who married Captain Hubert White, ran it as a boarding house. In his later years, Captain Hubie, as he was known, spent long hours on the porch, reportedly taking the occasional potshot at a passerby with his BB gun.

31 – The Pelletreau House and Shop – Built in 1686, the shop where silversmith Elias Pelletreau and some of his descendants worked at their craft and sold supplies survives, though the Pelletreau home is long gone. Elias Pelletreau, the family patriarch, was a Revolutionary War hero and an extremely successful artist with silver and gold.

32 – The William S. Pelletreau House – The pre-Revolutionary house associated with Southampton’s eminent historian William S. Pelletreau was occupied by British General Erskine during the wartime occupation of Southampton. General Erskine slept there and took his meals across the street in the Herrick house. In the late 1850s, Pelletreau’s heirs were in possession of the house, which burned in 1916.

33 – Hallock House – Dr. George Horace Hallock, Southampton Village’s first doctor, built his house on South Main Street after being “called” to Southampton, which was without a physician. The family remained in Southampton where his descendant, David Horace Hallock, also became a prominent doctor.

34 – Captain Philetus Pierson House – Whaling Captain Philetus Pierson was in residence in this handsome Greek Revival house for most of the second half of the 19th century. His daughter married Captain Jetur Rogers and the couple also made it their home. More recently it was the residence of artist Fairfield Porter.

35 – Reeves House – This Italianate house, a village landmark, is believed to have been Henry Reeves’ boarding house, which could accommodate 50 people in 1877, according to a brochure published by the Long island Rail Road. Originally located closer to Jobs lane, it was moved south from the corner to make room for the tower shops c. 1925.