For decades, pilot Joe Moser didn’t talk about what had happened to him during World War II.

That’s because when he came home from the war in Europe, nobody believed him.

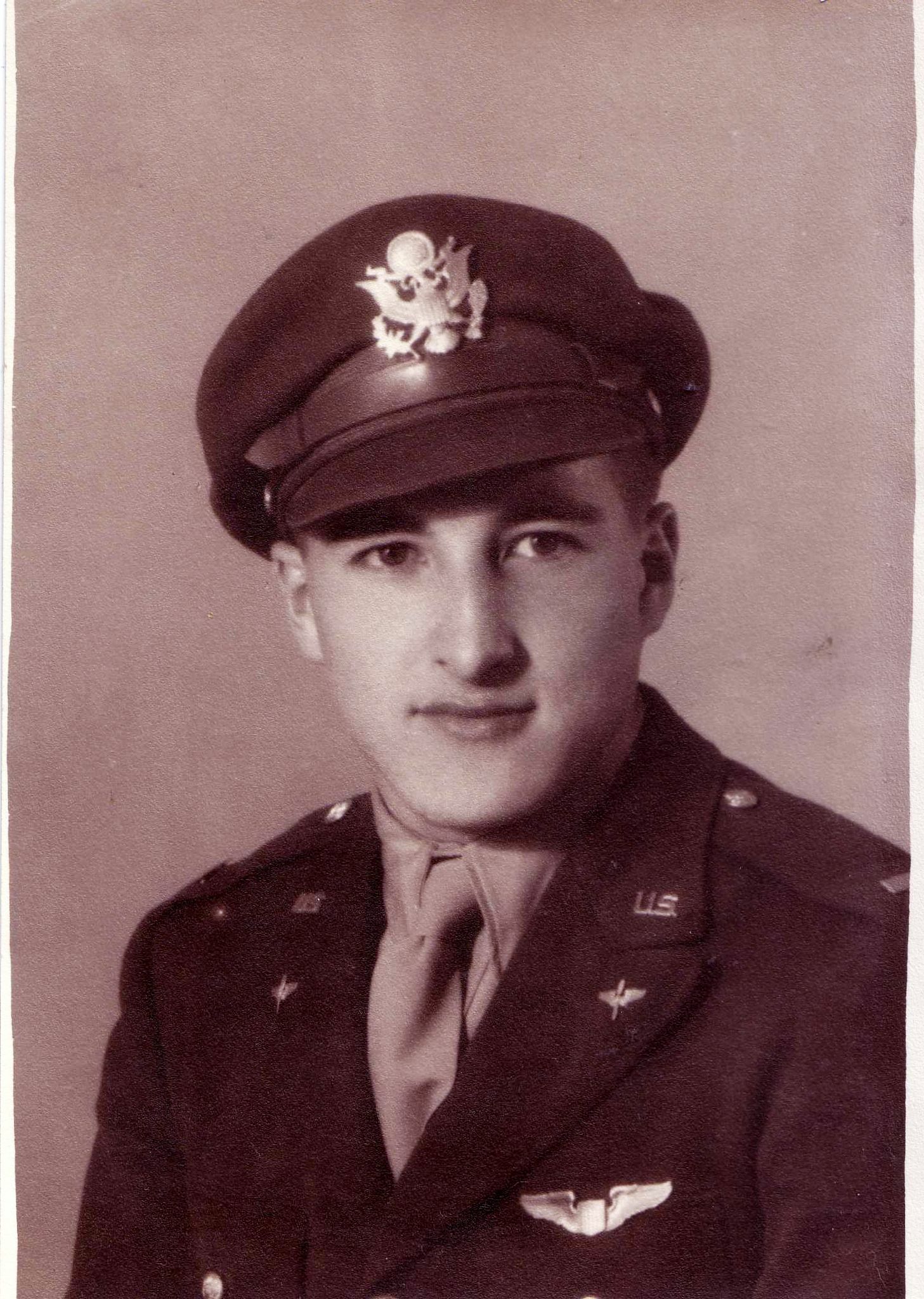

His story began on August 13, 1944, when Moser, who flew P-38 Lightnings as a lieutenant in the Army Air Corps, was on his 44th combat mission over occupied France. After being hit by enemy fire, he bailed out of his burning plane and, despite assistance from local farmers who tried to hide him, was soon captured by German soldiers. He was taken to the infamous Fresnes Prison near Paris where political prisoners had been housed since Nazi occupation began, and days later, found himself crammed onto a noxious and overcrowded cattle car heading east.

The final destination? Buchenwald, one of Nazi Germany’s deadliest concentration camps.

Moser, a 22-year-old farm boy from Ferndale, Washington, was one of 168 Allied fliers imprisoned in the notorious concentration camp during the final months of the war. Sag Harbor author Tom Clavin tells the little known but harrowing true story of Moser and his fellow pilots in his newest book, “Lightning Down: A World War II Story of Survival.” On Wednesday, December 8, at 1 p.m., Clavin will be at Rogers Memorial Library in Southampton to talk about the book.

Though Clavin has written many books about WWII, this tale was new to him and one he stumbled upon when he discovered an online obituary for Moser, who died on December 2, 2015, at the age of 94.

“Other than his time in the service, he never left his hometown,” Clavin said. “I got the obit from the local newspaper in the town where he lived. I saw he was one of 168 pilots sent to Buchenwald in 1944, and I’m thinking huh? A downed pilot sent to Buchenwald?”

That’s because throughout the war, in keeping with the terms of the Geneva Convention, captured Allied forces were housed in German POW camps where they received a modicum of care and occasional Red Cross packages.

But a concentration camp?

“The war had been over for 76 years. I thought, there can’t be any new stories,” Clavin explained. “We had heard new stories of pilots going to POW camps — and we all saw ‘Hogan’s Heroes.’ But why did they end up in a concentration camp?”

Being sent to Buchenwald was a case of incredibly unfortunate timing for Moser and his fellow fliers. Having been shot down two months after D-Day and with the Allies on the verge of liberating Paris, the Nazis were getting desperate, realizing they were on the brink of defeat. So they changed the classification of pilots like Moser to that of “terrorfliegers” (terror fliers) and, labeling them terrorists, justified sending them to Buchenwald instead of a POW camp.

“I found out there was a larger, untold story about captured pilots sent to die in a concentration camp. It’s the only time I’ve seen them designated as terrorists — which meant you didn’t qualify for the Geneva Convention,” Clavin said. It was one of the increasingly desperate Nazi motives.

“It seemed to be punitive, to punish these people and set an example,” Clavin added. “The Germans realized they were losing their grip on occupied France. They decided to start shooting civilians who helped the Allies and ship pilots off to concentration camps.

“This is the only transport I could find and a lightning strikes situation,” he said. “It’s a narrow story of these pilots and how they survived, though not all of them did survive Buchenwald — Joe got down to 105 pounds and was not in good shape.”

The Buchenwald pilots were not just Americans, also among their numbers were Canadians, Brits and even one Jamaican. Clavin noted that a key reason Moser and many of the fliers did survive Buchenwald was Col. Phillip Lamason, a pilot in the Royal New Zealand Air Force who became the de facto leader of their ranks. Lamason brought order and routine to a truly miserable existence at Buchenwald, and he kept the prisoner pilots as focused and united as could be expected under the circumstances.

“He was a remarkable man — like the Alec Guinness character in ‘Bridge on the River Kwai,’ but without the madness,” Clavin said. “He was maintaining discipline, and they were supporting each other. His words inspired them to stick together. He also faced death several times and at any moment in confrontation with the Germans.”

The pilots were held at Buchenwald from mid-August 1944 until the end of October, and for much of that time, were forced to sleep outside because of overcrowded conditions at the camp. Then Lamason heard through the grapevine that orders had come through that they were all to be executed within a matter of days. With the Allies closing in, Nazi leadership wanted the pilots’ presence totally erased so there would be no evidence of them having ever been imprisoned at the concentration camp. The Buchenwald crematorium would ensure their plan.

The date of execution had been set, but in order to not destroy what little morale there was among the men, Lamason made a decision not to tell the pilots.

“Instead, they came up with a Hail Mary plan,” Clavin explained. “There was at least one German speaking pilot, and he wrote a note and smuggled it to a nearby Luftwaffe airbase.”

That note made it into the hands of Hannes Trautloft, a high-ranking German flying ace who didn’t particularly like the Nazis but was loyal in his service to his country as a pilot.

“He reads the note and said, ‘This can’t be true. If it is, it’s a problem,’” Clavin explained. “It was a code of honor thing.”

So Trautloft and his adjutant arranged to inspect Buchenwald. As a high-ranking German pilot and a national hero, he couldn’t be denied access by those who ran the camp. During his tour, SS officers kept steering Trautloft away from the imprisoned pilots, who, after two and a half months in the camp, looked just like the other emaciated prisoners, right down to the filthy striped uniforms. The pilots had been warned ahead of time not to make a sound during his visit, upon penalty of death.

“He looks around and thinks the note is a fake. He’s turning to leave. One of the men yells out, ‘We’re here! I’m an American pilot. Come talk to us.’ The commandant tried to steer him away, but he has a conversation with them and realizes the note is true,” Clavin said. “There are pilots in the concentration camp, and they are to be shot in three days.”

The desperate plan worked, and miraculously, Trautloft’s report made it up the chain of command and the order soon came to move the pilots out of Buchenwald. Within days, the surviving fliers who were sentenced to death found themselves boarding cattle cars once again, this time bound for Stalag Luft III, a POW camp in eastern Germany, where the conditions and the food supply may have been substandard but was far superior to Buchenwald.

“They do go to a POW camp, and it’s good news for a while,” Clavin said. “But then comes January of ’45. This camp is built for 1,500 and there are 10,000 guys in it. The Russians are closing in on one side, the Allies on the other. It happens to be the worst winter in years.”

The Germans decide to clear out the camp and force the prisoners to march more than for 60 miles in snow and sub-zero temperatures to get to another camp.

“Of 10,000, 1,300 died,” he said. “If a German felt merciful, they would kill them.”

Though it seems that rather than moving the POWs, it would have been easier for the Germans to simply abandon them, Clavin explains that it may have been something akin to a hostage situation.

“The German officers felt if worse came to worse, they could cut a better deal or surrender more easily,” Clavin said. “The Germans also joined the march to get away from the Russians.”

But Moser’s ordeal was far from over. He and the remaining POWs were marched to Stalag XIII-D, and two months later, to Stalag VII-A, as the Germans continued their attempts to evade capture, despite the hopelessness of their mission. The conditions at these two horribly overcrowded camps were as deplorable as those at Buchenwald. Fortunately, in April 1945, the Americans arrived at the camp in time to save Moser, though many others perished in the days and weeks prior to liberation.

“He was laying there near the entrance to the camp with no strength to do anything else when the tank came in the front gate,” said Clavin, who noted that it would take Moser another two months to get a transport back to Washington State.

“When he got home, his local American Legion asked him to talk about his experiences. No one believed him,” Clavin said. “Buchenwald? Death marches? They said he was lying to build himself up.”

So Moser ended up doing what a lot of men from his era did after the war. He got married, had kids (five to be exact), got a job (as an oil burner service man) and lived a quiet life.

“He didn’t talk about it for 40 years. He didn’t even tell his wife and kids,” Clavin said. “He wanted life to be as normal as possible, but he didn’t sleep for 40 years. There was no way of getting this out.”

Then at some point in the late 1970s, several of Moser’s fellow pilots began to reach out and reconnected with one another through the KLB Club (Konzentrationlager Buchenwald), an impromptu fraternal organization they had started during their imprisonment at the concentration camp as a way to boost morale.

“A couple guys said, ‘Let’s revive it and support each other.’ At least they could talk about the fact that they didn’t just dream this,” Clavin explained. “Over time, they were able to talk to others and word spread in the POW community that this had happened.

“As far as anyone knows, this was the only group ever sent to a concentration camp,” he said. “The German efficiency meant that paperwork followed the pilots from camp to camp. After Joe’s POW camp was liberated, one of the original pilots walked into town and found the Gestapo headquarters. He also found their paperwork, and it survived for decades in his basement, and he then distributed it to the other guys.”

Though Clavin only learned about Moser’s harrowing story through his obituary, it turns out that the details of his experience had been documented prior to his death.

“Joe told his family he didn’t want the story to die with him,” Clavin noted. “He went to Gerald Baron, a businessman in Ferndale, and said, ‘I want to put down my story for my family and friends. If I tell you, will you write it down?’ That’s what Baron did. He had it privately printed for family, friends and the local American Legion.”

While that book, “A Fighter Pilot in Buchenwald,” told Moser’s personal story, there was much more for Clavin to uncover in terms of the other players involved in the case of the pilots sent to Buchenwald.

“There was a bigger story that I had to research separately,” Clavin said. “From the time I saw Joe’s obit to publication was six years.”

Some stories just have to be told.

Tom Clavin discusses “Lightning Down: A World War II Story of Survival” on Wednesday, December 8, at 1 p.m. at Rogers Memorial Library, 91 Coopers Farm Road, Southampton. To register, visit myrml.org.