By Michelle Trauring

Jane Weissman usually travels alone — by both circumstance and design, she said — and she loves paper maps.

If she can, she rents a car and plots her routes by hand, avoiding interstates as much as possible. It gives her a truer sense of a place, she explained during a telephone interview from her apartment in Greenwich Village, eight months back from a road trip around the Southwest, though the fine red rock sand likely lingers.

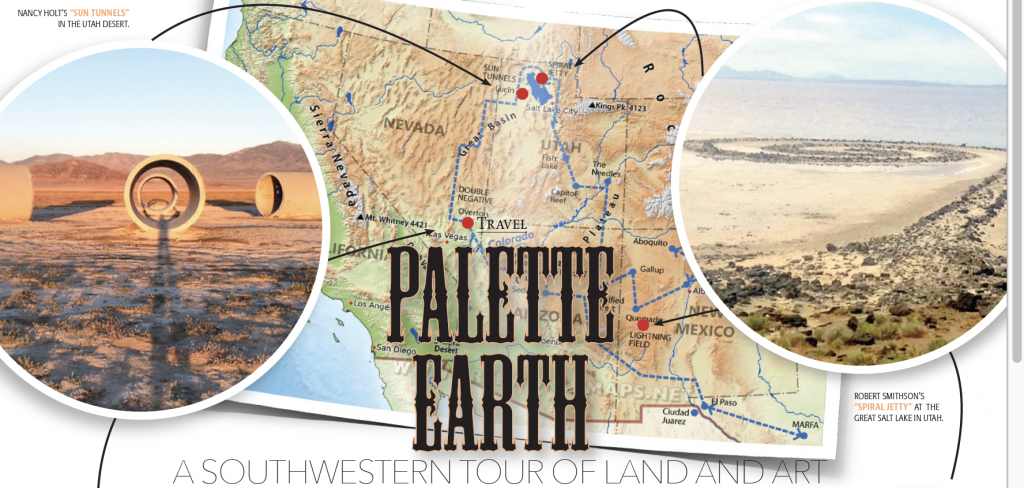

She had landed in El Paso on May 31, picked up her Nissan Rogue — “which I thought was extremely funny,” she said — and started a month-long journey that would see five states, 4,566 miles and four iconic land art sites — the impetus for the trip, and subject of her talk, “Isolation & Light: 1970s Land Art in the American Southwest,” on Saturday at Golden Eagle Artist Supply in East Hampton.

[caption id="attachment_75907" align="alignright" width="432"] Jane Weissman in the Sun Tunnels.[/caption]

Jane Weissman in the Sun Tunnels.[/caption]

“In the early 2000s, a book appeared called ‘Spiral Jetta,’ where a young woman from Chicago goes on a journey visiting land art sites. And I read the book and I said, ‘Well hell, if she can do this, I can do this,’” said Weissman, who is a mural artist and historian. “Ten years later, I’m 71 and I say, ‘Okay, this is the year. This is when I’m gonna do it.’ Here is this movement that is not well known, and even if we know about these sites, who’s been there? They’re not easy to get to.”

That is precisely the point. In the late 1960s, a group of pioneering artists began rejecting traditional museums and commercial galleries, regarding them as “stale,” “senseless” and “dead,” Weissman said. They wanted to leave the big urban centers and boring experiences behind, and use new materials.

So they headed to the Southwest: Nevada, Utah and New Mexico. Boundaries were breaking everywhere, from the anti-war movement to the environmental movement to the Civil Rights movement — and now in the art world, as well.

“These guys wanted to get away. They were looking for big, wide-open spaces that were far away from everything,” she said. “And that’s why I called my talk ‘Isolation & Light.’ Those are words that are used by the artists in different contexts. They found what they wanted out west.”

Early sculptures using natural materials like dirt, rocks and plants evolved into process-based explorations and site-specific interventions that incorporated the surrounding landscape, introducing new objects and, in some cases, subtracting — as was the case with Michael Heizer’s “Double Negative” at Virgin River Mesa in Nevada, where he and his crew carved out 240,000 tons of rock from facing cliffs to form two gargantuan vertical trenches.

“When it was created in 1969, it was 50 feet deep, 30 feet wide and the sides were sheer. So it was very clear that this was a human intervention. Now, almost 50 years later, the sides are pretty eroded. So these two big holes in the ground look like any other canyon that you would come across when you’re driving around,” Weissman said. “I have to say, and I realize this later, I wasn’t terribly impressed with ‘Double Negative.’ I mean, it’s two big holes in the ground, and he talks about that. He said, and I’m paraphrasing, ‘Just because there’s nothing doesn’t mean it’s nothing.’ And, of course, it’s true. It’s about negative space.”

Weissman had the opposite reaction to her next stop in the northern Utah desert, where she camped for two days outside four 18-foot-long, 9-foot-wide, open concrete cylinders laid out in an open X configuration near the Great Salt Lake — for only the most devoted of land art enthusiasts to see.

Artist Nancy Holt called them “Sun Tunnels.”

[caption id="attachment_75906" align="alignnone" width="640"] The Sun Tunnels.[/caption]

The Sun Tunnels.[/caption]

“It’s just so beautiful. It’s flat and the colors are gorgeous and you just come across the tunnels. I arrived at three in the afternoon and there was a mother and a daughter there, so it was nice to have companions for my first night,” Weissman said. “We just watched the sun play on these tunnels. At night it’s golden; in the morning it’s purple and orange. The second day, I was alone for 24 hours and it was just glorious. I would have been glad to have just stayed there another few days on my own, but I ran out of food.”

She sighed at the memory. “I had no idea I would respond to it in the way I did.”

On the opposite side of the lake sits “Spiral Jetty” by Holt’s late husband, Robert Smithson, who died in a plane crash in 1973 — just three years after he created his masterpiece. He was 36.

“I think many of us have grown up enamored with the idea of ‘Spiral Jetty,’” Weissman said. “It was created in 1970. Within a few years it goes underwater; it doesn’t emerge until 2002, and when it did, the descriptions were that it was white rock and pink water, where the salt and algae had colored the basalt rock used to create the jetty. It’s like, ‘What is this about?’”

As the years passed, and much to Weissman’s surprise when she walked down to the lake, the white and pink morphed back to black and blue.

“Smithson expected it to change over time and he didn’t mind that. He welcomed it,” she said of the artist, who was the quasi-philosopher of the land art movement. “But for me, it was like, ‘Wait a second. Where are all the rocks? Where’s the pink? Where’s the white?’ This was more like a nice sand spiral with a few rocks, so it took me a while to figure it out.”

Her final stop took her to a small cabin in the remote high desert of New Mexico, where Walter De Maria planted 400 20-foot poles, spaced 220 feet apart, in the ground, a site called “The Lightning Field” — its specific location a well-kept secret, and host to no more than six visitors per night.

“I didn’t see any lightning, but the experience was lovely. It was more of an intellectual one than an emotional one,” she said. “You have to be there for 24 hours. That was stipulated by Walter De Maria. You have to reserve a room, and it’s not easy to get one. I was on a waitlist. But I got one and it was perfect because they gave it to me for June 22, which allowed me to make it at the end of my trip and do this wonderful circle.”

On June 30, Weissman returned her Nissan Rogue in Albuquerque and flew back to New York, reflecting on her trip from the air.

“All I can say is I’m so glad I did this. I just felt great that I had seen these things, that I navigated these roads. It was an amazingly easy trip, oddly enough,” she said. “Except I did get stranded overnight on Brin’s Mesa in Sedona. I lost the trail while I was hiking. Yeah, whoops.”

During an exit interview with the search and rescue team the following morning, the lead ranger asked her what she would have done differently. She would have brought a sweater, she said, clothed in nothing but shorts and t-shirt, as well as more food and water, and a knife — to which he nodded.

But it was only when she suggested a hiking partner that he said, “Bingo.”

It was the last item on her list.

“You probably can get a sense: I don’t have any fear. Obviously, I wouldn’t have been going up Brin’s Mesa on my own,” she said. “There is something about doing these things on your own. It’s a challenge. And it’s not a value judgment, but some people aren’t wired for this kind of thing. I remember when I hiked in Nepal, a friend writing me, ‘You’re paying to do that? I would pay not to do that.’ And it was like, yeah, okay, I get it. It’s not for everyone.

“I like being with people, but I am not good in a group,” she continued. “Nobody can tell me we’re going to do this now. I need to do it in my own way, my own rhythm. It’s just a lot more fun, and you discover more that way. And isn’t it really about discovery?”

Jane Weissman will present her talk, “Isolation & Light: 1970s Land Art in the American Southwest” on Saturday, January 27, at 5 p.m. at Golden Eagle Artist Supply, located at 144 North Main Street in East Hampton. Admission is free. For more information, please call (631) 324-0603 or visit goldeneagleart.com.