Lee Davis, a man of many careers but one lifelong passion for the musical theater, died on Sunday, August 28, at Southampton Hospital after a long illness. He was 81.

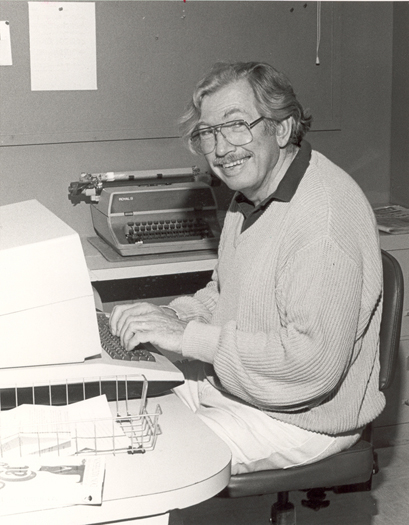

Critic, teacher, radio personality, biographer, impresario and playwright, Mr. Davis, a native of Westhampton, was perhaps best known to local readers for his “Now & Then” column in the Western Edition of The Southampton Press and its predecessor, The Hampton Chronicle, and for his theater criticism, written with the verbal exuberance that was his signature style.

With his gift of gab and broadcaster’s baritone, he also attracted an appreciative audience for his long-running radio program, “The American Musical Theater,” launched in the pioneering days of WPBX from what he once described as “a broom closet” on the campus of Southampton College. The program weathered the station’s many upheavals and eventual transition to Peconic Public Broadcasting and survived for decades as a Sunday afternoon favorite.

In the wider world, Mr. Davis was a respected authority on the American musical theater and its history, having treated the subject in typically lively fashion in his writing, lectures and classroom discussions. In books like “Bolton and Wodehouse and Kern” (1993) and “Scandals and Follies: The Rise and Fall of the Great Broadway Revue” (2000), he shed new light on the development of this uniquely American art form. Such seminal works impressed theater professionals and devotees alike, and he was often asked to lend his skills as scholar, writer, narrator and all-round impresario to put together the kind of theatrical tributes that were familiar to audiences at Guild Hall as “The American Theater Salutes Series.”

The series attracted a very loyal following, according to Josh Gladstone, Guild Hall’s artistic director, who spoke for Guild Hall’s board and Executive Director Ruth Appelhof in announcing that a seat in the John Drew Theater is to be named for Mr. Davis “in honor of all the years he brought a lot of happiness to audiences.”

Mr. Davis’s son and sole survivor, Chris Davis, who has inherited his father’s fondness for the musical theater, often collaborated with him, serving as his lighting designer. What never failed to impress him, he said, was “the caliber of performers” that his father was able to bring together for his shows. The respect and love they felt for his father became especially evident, he said, when, in “an explosion of emails” they spread the sad news of his death.

Born on January 14, 1930, Lee Allyn Davis grew up in Westhampton. In a 2007 interview, he recalled that he knew he was “hooked” by the world of the theater when he was no older that 8 and his parents took him to a revival of Rodgers and Hart’s “A Connecticut Yankee.” Once the spark was ignited, family friends like the librettist Guy Bolton, his sometime collaborator, writer P.G. Wodehouse, and the creator of the Radio City Music Hall Rockettes, Russell Markert, added fuel to the fire, filling the boy’s head with tales from the alluring world of show business.

Mr. Wodehouse and Mr. Bolton, both Westhampton area residents, were patients of Mr. Davis’s father, Dr. Leray Davis, an old-school country doctor whose kind deeds and competence often figured in his son’s columns. As a young boy, Lee Davis occasionally caddied for the two old theater men, who had been creative collaborators in their prime and remained friends in old age. In 2006, Mr. Davis’s thorough knowledge of the third member of the trio, Jerome Kern, made him the obvious choice when the New York Historical Society needed a script and a narrator for its tribute to the composer.

From Westhampton Beach High School, Mr. Davis went on to Syracuse University, where he tried his hand at acting, and even singing, in a production directed by fellow student Jerry Stiller of “Seinfeld” fame. The experience convinced him that he was not an actor, as he later acknowledged, but did nothing to diminish his ardor for all things theatrical.

After Syracuse, a Fulbright fellowship took him to Denmark, where he directed student plays in English, among other things. Then it was on to one of those youthful jaunts around Europe, living by his wits, writing material for comedy routines in the last days of the big nightclubs.

Back in the States, Mr. Davis taught high school English in Westchester, a 27-year pedagogic career during which he directed all of the school’s shows, according to his son Chris, and made his mark with an exciting addition to the high school curriculum.

“He established the first high school humanities program in the nation,” according to his friend Mary Anne Gaetti-Garson, who first met Mr. Davis in the 1970s at an educational conference. They stayed close friends, and after delivering a eulogy at funeral services held for Mr. Davis on September 1 at the Westhampton Presbyterian Church, she elaborated on their friendship, recalling that a few years after the conference Mr. Davis left teaching and “just exploded. He just did everything—books, columns, radio, Guild Hall, teaching at Southampton [College].”

Having inherited his parents’ house in Westhampton overlooking Moriches Bay, Mr. Davis made it his home and launched his writing career in earnest. To make a living, he was sometimes obliged to write on offbeat subjects, but not even a daunting series of books on disasters batted out for Facts on File could distract him for long from what he once termed his “most abiding and indestructible devotion.”

“He and I shared that common interest,” said his friend Michael Disher, who is currently director of theater at the Southampton Cultural Center but cemented his friendship with Mr. Davis when both were teaching at Southampton College. Mr. Disher, whose shows at the college were reviewed by Mr. Davis, recalled that he was initially terrified by the man whose friendship he later came to cherish.

“He could be very pointed, very candid,” he said, though later he realized that “what Lee was always trying to do was provoke and promote us to be better artists, not to settle for mediocrity.”

Melissa Errico, who was Mr. Davis’s singer of choice for his Guild Hall series, also spoke of his generosity in seeking always to bring out the best in performers like herself. “He wanted everyone to shine, and he knew how to choose songs so that every singer would shine brightly,” she said.

Perhaps no one has ever been in a better position to appreciate Lee Davis’s approach to theater and theater criticism than Andrew Botsford, who edited Mr. Davis’s copy for more than 20 years as associate editor at The Southampton Press, and also acted in many Hampton Theater Company productions that were reviewed by Mr. Davis. He could be prickly about his prose and quick to defend it from perceived editorial meddling, Mr. Botsford said of Mr. Davis, but he was quick to add that he very much admired his ability as a critic to express his opinions with absolute integrity and yet do it gently, softening his reservations with words of encouragement.

And when nobody’s professional pride was involved, Mr. Botsford said he liked nothing better than to talk theater with Mr. Davis.

“Because he was a theater critic, and I a lifelong devotee, we both got a big rush discussing what the playwright had in mind, what the director and the actors did with it—all the intricate relationships and interesting nuances.”

Sparks flew, and beneath the excitement was a seriousness of purpose that singer Melissa Errico certainly felt.

“He could listen to ‘They Can’t Take that Away from Me’ or ‘Let’s Call the Whole thing Off,’ and in his eyes you could see that he felt those song were

important

,” she wrote in an e-mail. “He’d want his singers to be silly and passionate and carefree, but underneath he was on a mission that these songs and that era never be forgotten or made crude.”