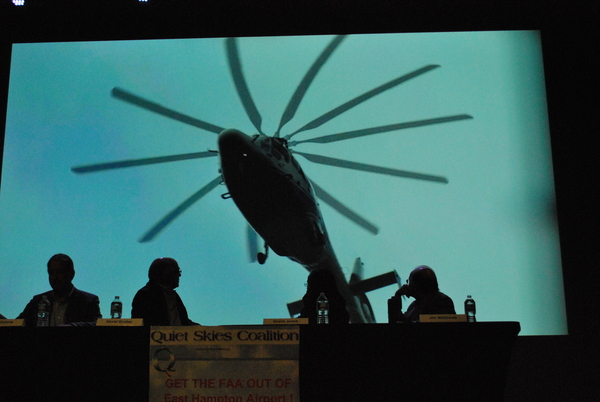

Life-sized helicopters soared across the giant screen at LTV Studios. Members of the audience winced. The film’s volume was set to just 10-percent below the decibel level of an actual flight over Frank Dalene’s Wainscott home.

Members of the Quiet Skies Coalition gathered at the studio, within earshot of East Hampton Airport, on October 26, to present their case that East Hampton Town should stop taking Federal Aviation Administration grants for capital improvements at the airport in order to gain greater local control over flights and cut back on noise. Mr. Dalene, the vice chairman of the coalition, has been recording helicopters passing over his house for three years.

The forum was the group’s response to opponents, led by Councilman Dominick Stanzione and the East Hampton Airport Alliance, who argue that even if the town rejects federal funds it will not be able to simply take control of its skies. They favor other methods of mitigating noise such as installing a control tower and charting a South Shore route for helicopters. On October 11, during a presentation set up by Mr. Stanzione, the Town Board’s aviation attorney, Peter J. Kirsch, said rejecting grants would have little impact on the town’s power to regulate air traffic and trying to impose restrictions would be a costly and risky legal route.

But at the forum last Wednesday, Sheila Jones, an aviation attorney who represented the Committee to Stop Airport Expansion in its 2003 lawsuit against the FAA, said swearing off federal funds would free the town from grant obligations that restrict it from setting curfews and barring certain types of aircraft—a position anti-noise activists argued for years even before they formed the Quiet Skies Coalition in August. The group already has 230 members on the South Fork and is starting a North Fork chapter, according to Mr. Dalene.

Sitting at a table with a sign that read “Get the FAA out of East Hampton Airport!” Ms. Jones told the approximately 35 attendees that a legal rule called the “proprietor’s exemption” allows municipalities to restrict traffic at their airports for the sake of public health or safety, breaking the FAA’s otherwise absolute control over the skies. She said New York City, for example, restricted hours and set noise limits at its heliport, and the rules held up in federal court.

Even if the town were free from grant obligations, the FAA and others could still challenge new airport restrictions in court, Ms. Jones said, although the process would be “radically different” than if the town was still under the grant restrictions. In that case, the FAA would be directly involved in the decision-making process and could claim breach of contract if the town defied the agency.

Because the Committee to Stop Airport Expansion and Ms. Jones reached a settlement with the FAA in 2005, the FAA agreed to not enforce four key grant assurances after 2014, according to Ms. Jones. The result, she said, is that East Hampton Town will be able to restrict aircraft traffic that year. Mr. Kirsch, though, has said the settlement will not stop the FAA and others from suing the town if it were to restrict access to its airport.

Reached by phone last week, Mr. Kirsch agreed with some the facts Ms. Jones presented, although he said she was playing down the legal risks of trying to restrict air traffic. He said the FAA, pilots and other parties were likely to sue the town if it tried to set curfews or ban certain vehicles—whether the town still has grant obligations or not—and the legal battle could cost the town millions of dollars and lost years.

“They have a tendency to consistently understate the risks associated with the policy they’ve asked us to pursue,” Mr. Stanzione said last week. He added that Mr. Kirsch was hired to provide unbiased legal advice to the Town Board, while Ms. Jones is advocating a particular position on behalf of clients she represented.

“If I was in litigation I would aggressively pursue the position that Sheila Jones argued, because that would be my job as an advocate,” Mr. Kirsch said. “And to be perfectly frank, I would hope she’s right.”

Mr. Kirsch disagreed, though, with Ms. Jones’ statement that the most severe penalty the FAA could impose if it won in court would be to deny the town grants and end its authority to impose certain charges. Mr. Kirsch said a judge could impose a permanent injunction preventing the town from putting certain rules in place at its airport, which he said has been the result of past cases.

Ms. Jones said East Hampton Airport could also ban the loudest class of aircraft—known as Stage 2 aircraft—which includes helicopters, by following steps outlined in the Airport Noise and Capacity Act of 1990. It can restrict quieter aircraft, known as Stage 3 aircraft, by following the same steps and getting additional FAA approval.

Mr. Kirsch has described the process as long and expensive, because it requires multiple studies.

The entire Quiet Skies Coalition forum, which included a question and answer session, is available on LTV’s website, ltveh.org, under “Video On Demand” and “Specials.”