By Joan Baum

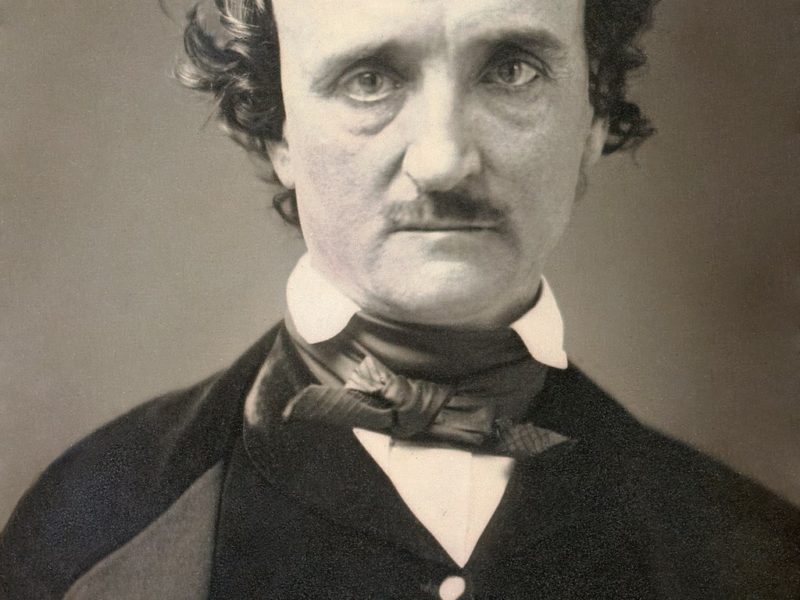

It’s short, free (just google) and, yes, another fictional take on a pandemic, but Edgar Allan Poe’s 1842 Gothic horror tale, “The Masque of the Red Death,” anticipates some of our own dismissive attitudes based on willful ignorance and crass indifference.

It’s ironic that Poe’s story is set “toward the close of the fifth or sixth month,” after Prince Prospero, the ruler of an unnamed kingdom, holed up to escape plague in one of his luxurious crenelated abbeys, along with 1,000 invited royals. The time frame is about the same as ours, when, this past February, leaders of our own land gave begrudging recognition to the fast-moving novel coronavirus, though the acknowledgment was — and still is — accompanied by various kinds and degrees of denial.

Poe, who originally called his tale of bubonic plague “The Mask of the Red Death: A Fantasy,” changed the title three years later to “Masque,” perhaps because he wanted to signify the “masquerade” at the heart of the story: the disguising costume ball that Prospero puts on for his “hale and light-hearted friends” as the plague rages without, having already killed half the population.

As to why Poe dropped “A Fantasy,” it is anyone’s guess, but the change works in deepening the delusion of aristocrats walled up with “gates of iron and welded bolts” and being “well provisioned with all the appliances of pleasure,” as though these could protect against the pestilence. Yes, the poor will get hit first and hardest, but … no one escapes.

The 14th century plague actually wiped out entire towns as partying went on. As Giovanni Boccaccio’s “Decameron” (1353) observes, some people even thought that one way to confront the Black Death (so named for the dark color of the rotting buboes) was to hide away and eat, drink, and be merry.

A master of the short story who memorably wrote about fashioning every detail or aspect to serve a “preconceived effect,” Poe knew what he was doing when he made his first paragraph a grim, dispassionate testimony to the swift triumph of the “hideous” and “fatal” disease. So, before the narrative gets going, the reader knows the outcome.

Prospero’s suite of unlit rooms go from east to west — from blue to purple to green to orange to white to violet and finally to red-black, red signifying “blood,” the “Avatar” of the plague, its “seal” being madness. Indeed, some of the revelers think Prospero is mad, though most, his “followers,” do not. Poe’s spectral sequence hardly reflects Newtonian physics, but it does emphasize the jarring progression of garish hues that lead inevitably to death.

But there’s an oddity. The story, a third-person narrative, inexplicably yields three times to first person as it evolves: 1) “let me tell of the rooms …”; 2) “And then the music ceased, as I have told”; 3) “an assembly of phantasms such as I have painted.” Moreover, the last paragraph’s five sentences all begin with a Biblical “And.” Someone is narrating, but it cannot be Prospero, who succumbs in the next-to-last paragraph. No Ishmael here, no survivors. So who is telling this tale?

Poe, notorious for paying homage to literary forebears by borrowing or plagiarizing, may (or may not) have had in mind Shakespeare’s Prospero, the exiled rightful ruler of Milan in “The Tempest” who learns and dubiously exercises sorcery to hold onto power. But this possible allusion offers no help in determining Poe’s narrator.

As the story drives to its inevitable finish, Poe describes a “gigantic clock of ebony” in the last dark red velvet room, its loud and peculiar hourly chime making orchestra and dancers temporarily halt their frenzy, “confused, meditative” — but then it’s back to the “voluptuousness” of the masquerade. They have been reminded but ignore what the chime tolls.

Until midnight. And then a grotesque masked figure appears, provoking horror. Prospero is convulsed, enraged that no one, including him, has moved to stop this terrifying figure. But finally he takes up a dagger and, with other revelers behind him, confronts the figure. And falls dead.

When the revelers reach out to the mysterious intruder, however, they grasp only “grave cerements and a corpse-like mask.” The clock chimes no more. “And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.”

What to make of it all? Could it be Death who narrates? Is there a lesson here? No need for one — and perhaps that is the lesson.

“The Masque of the Red Death” impassively exhibits the futility of trying to conquer or deny Nature or the human condition, which, in the words of the late Dr. Lewis Thomas, president emeritus of Memorial Sloan Kettering, who used to live on Main Street in East Hampton, includes “ease” and “dis-ease.” Not a comforting thought, particularly for Poe, challenged by his own demons and the tuberculosis that began to ravage his wife the year he composed “The Masque,” but an inferred reminder that it’s not that we live, but how.

Joan Baum is a writer who lives in Springs.

More Posts from Viewpoint

More Posts from Viewpoint