The majority of the architects who created some of the grandest and most unusual complexes during the golden era of leisure homes (1880 to 1930), when the Hamptons became the American Riviera, received their training at the L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

Architecture in this era was a gentleman’s profession, and most of these architects came from wealthy, socially connected families. While many of these professionals attended Ivy League schools and continued their architectural education at the few schools that offered formal architectural curriculums—schools such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Columbia University, the University of Illinois and Cornell University—the school with the highest standing and finest training was L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts. And, of course, Americans at this time still emulated the European tradition, particularly when it came with a pedigree.

More than 500 Americans studied at L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts from 1850 through 1968, when it closed its doors. Admission was open to foreigners by competitive examinations conducted in French.

In any given year, 600 students would apply for 30 places. The curriculum centered on the Beaux-Arts teaching method, which involved design in a studio setting, an atelier, each named after its patron professor.

While the older students helped the younger, the professor was always a practicing architect. Although theoretical design along with scientific courses rounded out the studies, the core of the program revolved around the esquisse, a rendered, preliminary design that would solve a sketch problem in a time frame usually under 10 hours and ending en charrette.

In French,

charrette

means “cart,” which alludes to the carts that were wheeled through the studios for the collection of finished drawings at the 11th hour, right before the critique. This system is still used in many schools today, and the term “charrette” still brings back vivid memories of my own architectural education at Syracuse and a grueling race against the clock.

The rationale behind this exercise was to teach mental fortitude and disciplined thinking from the outset of a project.

The Beaux-Arts method also encouraged the illustration of shades and shadows for the final rendering in order to articulate the significance of light and texture on an architectural surface. The work produced in these ateliers favored traditional styles, mostly neoclassical.

All of this, however, is not to be confused with “Beaux-Arts style” and the “White” architecture of the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago (also known as the Chicago World’s Fair), which the architect Louis Sullivan, a graduate of the L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts, said would set back architecture in this country by 50 years.

At first glance, the estates in the Hamptons designed by graduates of L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts might suggest a classical symmetry rooted in the aforementioned design methodology. A closer look, on the other hand, reveals a highly imaginative and eclectic collection of buildings that take cues from their clients’ programme as well as a sensitive response to site, context and environment.

McKim, Mead & White created the Montauk Association houses between 1882 and 1884 in the original shingle style. More than 125 years later, the houses still reflect an uncalculated simplicity in their massing and details.

These buildings served as the concept models for the larger commissions to follow and have been inspirational to generations of architects working in derivative styles such as post-modernism and the new shingle style (“McMansions”).

Edward Delano Lindsey (the fourth American to graduate from L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts), creator of the fanciful Maycroft (1886) in North Haven, paid careful attention to the orientation of the house on the site, which faced both the bay and Sag Harbor in the distance.

For Wooldon Manor (1900), architects Barney & Chapman concocted a seaside Victorian cottage with heavily draped interiors of dark wood paneling and ornamental moldings. The integration of exterior landscaping on an otherwise flat and open site turned the property into a little fantasy world all its own.

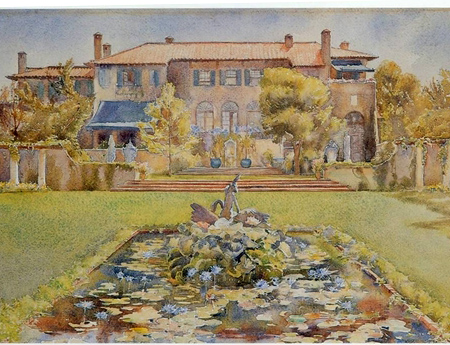

Black Point (1916), the 60-acre Gin Lane estate of Colonel Henry Huddleston Rogers Jr., designed by Walker & Gillette, was inspired by the Italian villas of the Renaissance. This mansion, used for entertainment, embodied the notion of procession as a theme against a backdrop of grand vistas. Main rooms, accessed one flight up, overlooked both the ocean and the formal gardens.

For the Woodhouse Playhouse (1917), Francis Burrall Hoffman Jr. devised an Elizabethan hall with a steep gabled roof and church-like nave. This was very much in keeping with the theme of Anglophilia, so prevalent in East Hampton’s architecture, as evidenced in half-timber shingle and stucco or thatched roofed houses. These homes are a constant reminder of the descendants’ proud heritage and their Puritan ancestors in Kent, England.

Bayberry Land (1918) and Chestertown House (1926), both by Cross and Cross, were completely different from one another. The former, a sprawling 314-acre estate on Peconic Bay, presented a stuccoed Arts and Crafts-inspired exterior with a slate roof against a formal Georgian interior. The latter, an oceanfront estate, exhibited a Georgian brick exterior of whitewashed bricks in a symmetrical façade facing Meadow Lane.

Each house was enormous, but the architects went out of their way to make both appear smaller. The roof at Bayberry Land, sweeping across two stories, made the three-story house look like two while anchoring it low to the landscape. Behind Chestertown House’s modestly proportioned street-side façade were two other wings, layered front to back, that truly concealed the 35,000-square-foot bulk of the house. Unlike the exterior, the asymmetrical interior reflected a programmatic agenda of separating private, public and servant spaces in order to showcase Henry du Pont’s collection of Americana.

Port of Missing Men, Colonel H.H. Rogers Jr.’s hunting box on 1,200 acres on Scallop Pond, was built as a retreat from the hustle and bustle of life in Southampton Village. And unlike anything the architect John Russell Pope had ever done before, he incorporated the existing 1661 Jackomiah Scott cottage into a larger H-shaped colonial revival house.

Pope, who was once called “The Last of the Romans” by Joseph Hudnut in an article in the “National Gallery of Art,” did include a natatorium in the classicist style. But, despite this one gesture toward his well-known style, the Port of Missing Men compound was basically woven into the historic fabric of the site and existing neighborhood.

L’Ecole des Beaux-Arts graduates William Lawrence Bottomley, Grosvenor Atterbury, Treanor and Fatio, Katharine Budd, Carriere and Hastings, Peabody, Wilson & Brown, and Trowbridge & Livingston, among others, also contributed to the fecundity of the Hamptons as an epicenter for new ideas and for articulating design values that continue to influence the art of architecture to this day.

Anne Surchin is an East End architect and co-author of “Houses of the Hamptons, 1880-1930,” Acanthus Press.

More Posts from Anne Surchin

More Posts from Anne Surchin