By Michael Shnayerson

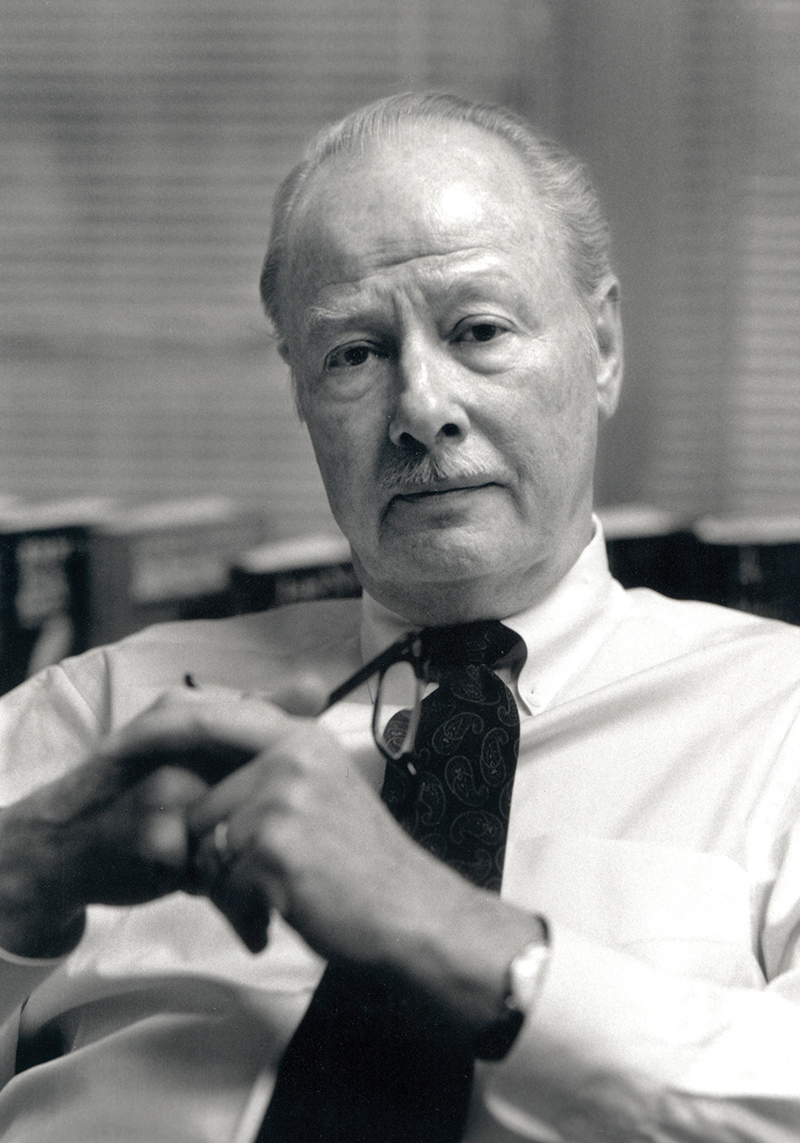

Robert D. Loomis, one of the last of the great post-war book editors, widely admired for his devotion to writers in his more than 50 years at Random House, with a breathtaking roster of prize-winning titles, as many in fiction and non-fiction, died earlier this week in a fall from which he failed to regain consciousness, surrounded by his wife, his son, and his pregnant daughter-in-law. He was 93.

Mr. Loomis was at Duke University in the late 1940s, the son of two doctors from Conneaut, Ohio, when he befriended a fellow undergrad as passionate about literature as he. As an editor at The Archivist, a student magazine, Loomis published stories by this young William Styron, and a legendary working relationship was born.

For a while, after graduating from Duke in 1949 and serving in the Army Air Forces, Mr. Loomis roomed with Mr. Styron in the campus town of Durham, North Carolina, in a house that became the backdrop for Mr. Styron’s great novel “Sophie’s Choice.”

Mr. Loomis had no thought of writing himself — his efforts were “just college stuff,” he later said. Instead, he eventually landed an editor’s job at Random House in New York, in 1957, in the golden days of publishing. The company’s founding editors, Bennett Cerf and Donald Klopfer, were still there, promulgating a devotion to writers, great books, and liquid lunches.

“Double bourbons,” recalls literary agent Esther Newberg. “Jack Daniels. And he could always function after lunch, which made you feel like such a lightweight.”

Mr. Styron was one of Mr. Loomis’s first Random House authors: the two worked on nearly everything Mr. Styron wrote.

“They could not have been more different,” explained Mr. Styron’s daughter, Alexandra. “Bob was soft-spoken and a gentleman. I never heard him speak above gentle tones, and my father was irascible and challenging.” Mr. Loomis was a calming influence; Mr. Styron was at his best with him. At their weddings, the two were each other’s best men.

With his calm and patience, Mr. Loomis edited many books that took years. Shelby Foote’s history of the Civil War began as one volume but grew to three — in longhand — over 20 years, a literary classic.

Mr. Loomis edited Neil Sheehan’s “A Bright Shining Lie,” a literary biography of Lieutenant Colonel John Paul Vann that became a history of the Vietnam War. That one was 14 years in the making and won both a National Book Award for nonfiction (1988) and the Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction (1989). In that same flush of brilliant success, Pete Dexter won the l988 National Book Award for his Loomis-edited novel, “Paris Trout.”

Few editors take on both fiction and non-fiction and win prizes for both: Mr. Loomis was the exception. He just liked both genres and saw no reason to choose one over the other. He edited all of Mr. Styron’s novels — and his dark late-life memoir, “Darkness Visible” — and all of Maya Angelou’s 20-some works.

Yet he also edited Jonathan Harr’s “A Civil Action,” a non-fiction investigation of a toxic river in Massachusetts — for which the research went on so long that Mr. Harr was reduced to maxing out his credit cards and sleeping on friends’ sofas — and saw it win the National Book Critics Circle Award.

He edited Calvin Trillin, whose impish humor mirrored his own, and Robert Massie, the Pulitzer-winning biographer of czars. Any one of these would have made an editor’s reputation.

Mr. Loomis was famously genteel and candid in his editorial comments. A writer would find lines of dots in the margins, usually with one word and a question mark, a word like … “boring?”

For most of his 54-year-career, the marks were made in pencil; he was the last Random House editor to switch to a computer.

Once in a great while, a book didn’t work, and Mr. Loomis had the painful task of having to say so. He drove from his house in Sag Harbor to Peter Matthiessen’s in Sagaponack to say he just didn’t feel confident about taking on books two and three of Mr. Matthiessen’s Florida trilogy; there was tension in both households for months.

He had to tell Mr. Styron that a war novel he had struggled with for years didn’t work. Mr. Styron was furious, recalled his daughter, but eventually grateful. “It was hard to do with literary lions,” Al Styron noted. “No one was a better lion tamer than Bob.”

Mr. Loomis’s first marriage, to the literary agent Gloria Colliani, produced a daughter, Diana, but ended in divorce. His second was to Hilary Mills, who started as a reader at Random House in 1973; the novelist Toni Morrison set them up on their first date. After they began living together, Ms. Mills wrote a critically-acclaimed biography of Norman Mailer. They married in 1983, and had a son, Miles, who is finishing his Ph.D. on China for Chicago University.

Miles’s wife Cara is finishing her own Ph.D., on Turkmenistan, for Cambridge College. The two are expecting their first child at the end of April.

Mr. Loomis was a long-time resident of Redwood. He loved Sag Harbor and was never happier than at the controls of his Cessna 172, which he kept for years at the East Hampton Airport. (He had trained as a pilot in the Army Air Force.) He loved flying up for the day to visit the Styrons on Martha’s Vineyard, or just buzzing around the East End with sometimes nervous riders.

“He always played the same joke,” recalled his friend Steve Byers: “‘I’m not feeling well, let me give you a few tips in case I can’t land this …’”

At social gatherings, Mr. Loomis could be reserved, and some friends struggled for conversation starters. Biographer Robert Caro learned the secret: you just asked Mr. Loomis what he was reading, and out came his boyish delight in whatever it was.

“I sort of always looked for him at parties,” Mr. Caro said. “When I got to know him better, I came to understand why I did that. Just to chat with him about a book — what could be better than that?”

Mr. Loomis’s retirement in 2011 shocked his authors, but Mr. Loomis himself had no regrets. Publishing had become a blizzard of sales conferences and PR obligations, far from the joy of working through a manuscript with its author, word by word. “I asked him, ‘Do you miss the work?’” recalled fellow Random House editor Peter Gethers, “because he was such a workaholic. But he was so totally relaxed with retirement.”

Mr. Loomis still read the occasional draft as a friend. He read James Salter’s last novel, the bestselling “All That Is,” “not as Jim’s editor,” noted Mr. Salter’s widow, Kay Eldredge, “since Jim already had a terrific one, but simply as a friend. ‘Have you ever thought of reversing the position of the last two chapters?’ Jim recognized immediately that Bob was right — and made the change.”

Two nights before his fatal fall, Bob and Hilary Loomis checked in with friends for “ZOOM” cocktails, and talk turned to what each guest was reading. One Zoomer was just starting in on “Our Man,” the biography of statesman Richard Holbrooke by New Yorker writer George Packer. Mr. Loomis had read it already, and his face lit up. “It is so great,” he enthused. “So well done.” He laughed. “And so gossipy!”

“He was part of this generation that’s almost all gone now,” Mr. Caro said. “Men and women who cared about every word. And he was one of the greatest of them. “