Before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, accessing mental health services was already a challenge, especially for children and teens. Many therapy centers were forced to put potential clients on waitlists, especially in more rural areas.

The fallout from the pandemic caused such a sharp spike in demand for services that many centers simply stopped offering a spot on a waitlist, knowing it would be months, even upward of a year, before they’d have any open appointments.

It’s something Joan Stong has witnessed firsthand, in her role as a child therapist at New Hope Rising, the Westhampton Beach-based health and wellness center that offers therapy services for adults and children. She says that demand has “increased dramatically” in an area where counseling services for children and teens were already limited.

It’s a problem therapists have been facing for nearly two years now. Most children and teens across the country have returned to in-person schooling, many are vaccinated or newly eligible to get vaccinated, and they have been seeing the resumption of several aspects of normal life. Still, the effects of living through a pandemic are exacting a heavy toll on their mental and emotional health.

In a moment when the worst of the pandemic seems to be in the rearview mirror, but the future is still unclear, therapists like Stong, as well as other health professionals, educators and parents, are still working through the process of finding their way forward and doing the best they can to help the children in their care.

While they agree that there are still many challenges ahead, they also expressed optimism that things are heading in the right direction for today’s youth — and that important lessons have been learned.

When you’ve got a soil-speckled earthworm wriggling in your palm, and your mask pulled down under your chin, it’s easier to forget about COVID for a while.

That’s something students at East Quogue School have learned over the last 20 months. Like students at many other elementary schools in the area, they’ve been spending more and more time outdoors, with teachers opting to take them for an exploration in the sprawling school flower and vegetable garden, where they can get a mask break and immerse themselves in nature.

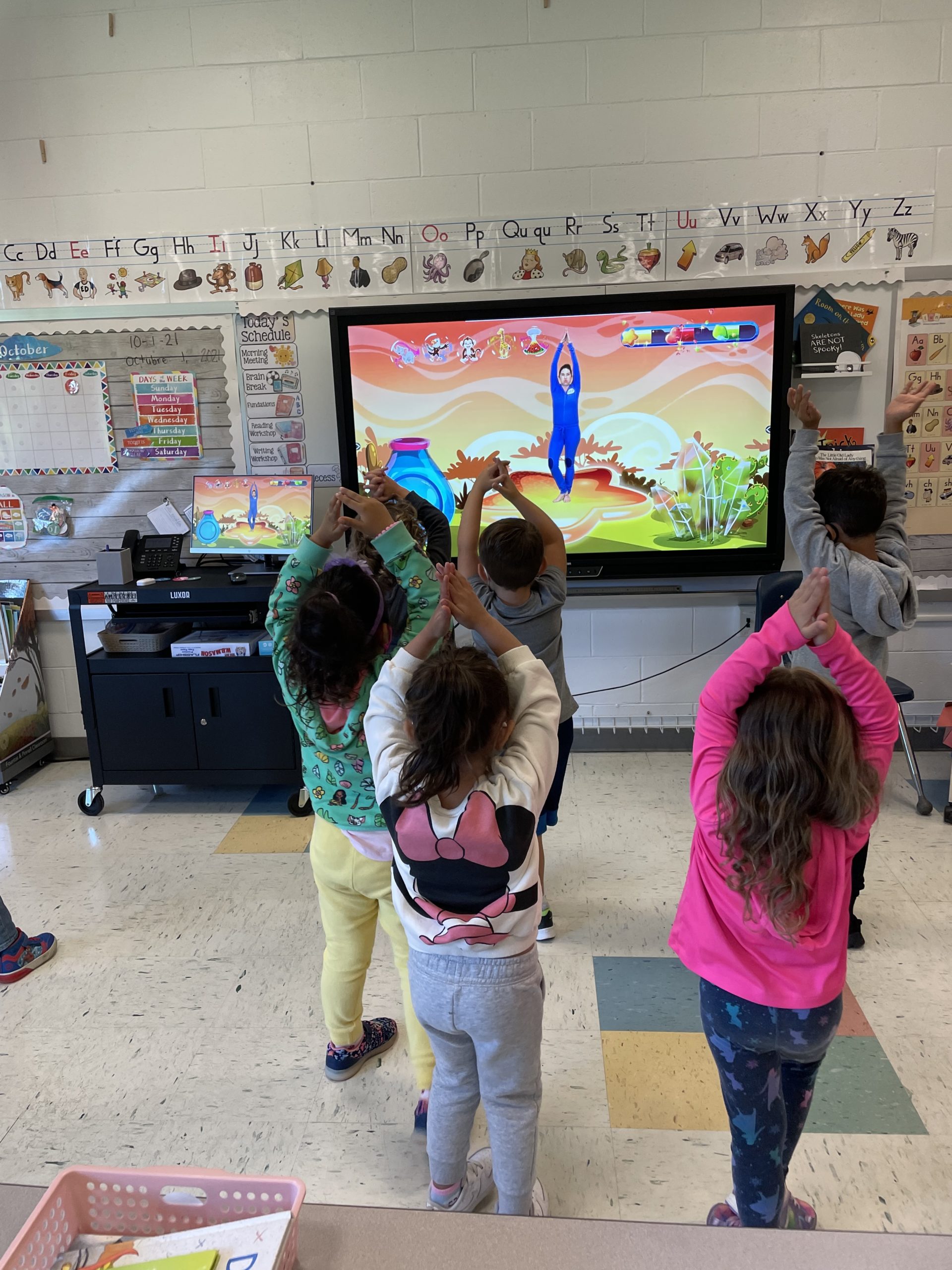

It’s one of several components the school has emphasized in its mission to help support the emotional well-being of the kindergarten-through-sixth grade students as they’ve entered their third school year affected by the pandemic. Whether it’s taking their kids outside to literally smell the flowers — and handle the wildlife — in the garden, or enjoying a few minutes of Cosmic Kids yoga alongside classmates, teachers are taking extra steps to help their students cope.

For Superintendent/Principal Rob Long and Assistant Principal Kelly Freeborn, finding ways to protect the mental health of students and staff has been at the top of their priority list.

“There’s a lot of things we’ve done here on a social and emotional level,” Long said. “Everything from our Responsive Classroom to our outdoor learning initiatives, to the additional staff we’ve hired.”

Spending more time outdoors has helped “lift spirits and make school more interesting,” Long said. Knowing that an outdoor break is coming in 20 minutes is the lifeline some kids need to make it from one part of the day to the next.

“You know you’re going to pick some vegetables, maybe find a worm or a turtle,” Freeborn said. “It gives the kids a chance to relax, get some fresh air and regroup.”

One step several schools have taken is having their guidance counselors and school psychologists play a more active role inside the classrooms, instead of having individual students who may need help going to them. Freeborn said the guidance counselor and psychologist are in constant contact about students who may need extra support, understanding that the challenges they faced or are still facing that have been brought about or exacerbated by the pandemic still need to be addressed.

“There have definitely been family dynamics that have changed, whether it’s parents having to return to work, or being in a new job or a student having a new family make-up, or an immigration situation,” she said. “Students may have home lives that are more strained or more anxiety around the home, and students bring that with them here.”

Some of the same strategies are being employed in the Sag Harbor School District. Michelle Grant is a guidance counselor in the school and has been spending a lot more time in the classrooms as well.

She said this year has been an “interesting balance,” noting that students have been “excellent” about wearing their masks, with barely any complaints, and adding that they seem to be responding well to more time outdoors, either in phys ed classes, in the garden, or when classroom teachers take them outside for a lesson or two during the day.

“I think we’ve always sort of had permission to be outside, but now it’s almost mandated,” she said.

There are challenges at every age level, and Grant said they’ve tried to pay particular attention to the kindergartners, who came into the building with much less socialization than they would have in a normal year.

To address that, they’ve been getting a once-weekly workshop, taught by Grant, on social-emotional learning, focused on themes like self-awareness, self-regulation and decision making, something Grant said she’s always been eager to incorporate into the curriculum in that way.

“We’ve been focusing on them understanding the concept of feelings, and how feelings can be big or small but they’re never wrong,” she said. “It’s about how you handle the feeling.”

While the younger students may need more of this kind of education than the older students, Grant pointed out that in many ways, surviving the pandemic has been easier for them.

“For the most part, the kids are rolling with things, especially the 5-year-olds, because they’ve been doing this since they were 3 years old, so it’s become such a big part of their lives already,” she said. “The older kids are the ones who feel like they’ve missed out on more.”

Dr. Wilfred Farquharson is a licensed child psychologist and the director of child and adolescent psychiatry services at Stony Brook University. He said continuing to find creative ways to help stimulate the mind and switch up routines has been especially important for young children.

“You have to have creative ways of getting a young person’s thoughts and feelings out,” he said. He’s seen parents work very hard to do that for their children, too, especially back when most children were in remote schooling, but said it’s hard to replicate what professional educators do, and being back in a classroom setting has been a big step in the right direction for children battling mental health challenges.

“Kids need structure and stimulation,” he said. “Not having that social learning component adds to the lack of stimulation and structure.”

Of course, the return to school after so many months learning online has created challenges for children of all ages this year as well.

“Kids who struggled with anxiety before [the pandemic], we knew we’d have trouble getting them back into school,” he said. “That environment is always tough for those kids anyway, and compound it with the fact that now everyone has to do social distancing and adhere to new protocols. They’re having homework again, too. The educational demands are increasing as they’re trying to get back to normal, and it’s resulting in more distress for young people.”

There’s a long list of reasons why children of all ages could benefit from therapy, and Stong has noticed that living through a pandemic has erased some of the stigma or reluctance associated with seeking out help.

“Kids are saying now that therapy is actually kind of cool,” Stong said. “It doesn’t have to be drudgery — it can be interesting and empowering.”

Stong said that over the last year she’s seen fewer kids putting up resistance and more kids who have been “willing participants” in the process. Stong has one client, a 12-year-old, who told her she researched her online, and that children will even talk about their therapists in their friend groups.

While the increased levels of cooperation can help therapists more effectively do their jobs, Stong said, there still are plenty of challenges. Addressing socioeconomic disparities that have always existed and have in many cases been widened because of the pandemic are key to helping certain children.

“The reality is that families or individuals can come into my session for 45 minutes to an hour and we can teach them coping skills, but if they go home and they can’t put food on the table for their kids, it will have an impact on them,” she said. “As social workers, we really try to also provide clients with access to resources in the community to help them with that.”

As the pandemic has moved forward in time, the issues therapists and social workers are addressing have shifted and evolved as well. The return to in-person schooling is an undisputed benefit for kids, but transitioning back into the classroom can be its own kind of trauma for certain children. For younger children, separation anxiety has been an issue, while for older children, transitioning back into social settings has been a challenge. Young kids who may have always had a hard time detaching from their caregivers at school drop-off now may have extra fears, coupled with many months of being unaccustomed to having to leave their side.

“There are fears of, what will happen to Mom if I’m not there? Could she get COVID and get sick or die?” Stong said, adding that children with those issues regressed during the pandemic, and working back to where they were has been an ongoing process.

Despite the challenges that still exist, and in light of new ones that arise, there is broad agreement that there are plenty of silver linings for children and their parents after living through a pandemic that has lasted much longer than anyone was initially expecting.

“Kids are so resilient,” Stong said. “It’s amazing to see how kids who have experienced different traumas have been able to move through it using different resources.”

So many months in isolation have certainly had many downsides, but Stong said that in many instances the big increase in time families have spent together over the last nearly two years has been helpful.

“The integration of family and connections between family members has evolved a bit more,” she said. “In homes that were pretty functional, it strengthened the family relationships.”

That is key for success in any kind of therapy situation, according to Stong.

“One of the things to really drive home is how important it is for parents to be involved in their child’s treatment,” she said. “As a culture, we become so focused on these larger social issues, that sometimes we don’t focus on what we have control over on a day-to-day basis, and that control resides within our homes and what we give to our children.”