His shift was almost over when the band saw—as swiftly as it slices through the toughest steaks, bone and all—suddenly severed a large hunk of Carl Jones’s middle finger.

In a split second that Monday afternoon on September 12, Mr. Jones had gone from chopping short ribs with a speedy, toothed metal band—a routine task for the experienced butcher—to facing the far more daunting prospect of having a mangled, bloody digit on his right hand, his dominant one.

What happened next, however, beat the odds, combined modern surgical techniques with medieval methods, and made history in one Southampton Hospital doctor’s book, forming a special surgeon-patient bond in the process.

Mr. Jones, who works in the meat department at the King Kullen supermarket in Bridgehampton, is the father of five children, the sole breadwinner in his family, and is engaged to be married. Butchering has been his livelihood for 17 years and is the only job he knows.

The odds for a successful finger reattachment were already stacked steeply against him. The closer to the fingertip, the tinier the capillaries, veins and blood vessels become, making reattachment surgery that much more challenging. They are so miniscule—thinner than a fine pen stroke on paper—that they are nearly invisible even to a surgeon’s eye under the most powerful magnification.

At a diagonal slant about 2½ inches from the tip, Mr. Jones’s injury meant a diminished chance of using that finger again. Tossing around a football with his children—C.J., 15, Jasmine, 9, Celina, who turns 8 on October 17, Jarred, 4, and Ryan, who will be 11 months old in November—would be greatly inhibited for the athletic dad, a Shirley resident, not to mention common tasks like buttoning a shirt.

Plus, as a pack-a-day smoker for at least 10 years, he faced a greater risk that his blood vessels would spasm than a patient who does not smoke.

“From a purely technical standpoint, it’s the most difficult, successful microsurgery piece I’ve ever had,” explained Dr. James Brady, the surgeon who overcame initial voices of doubt in his head to do what he first deemed impossible and later termed a miracle.

Microsurgical replantation, as it’s known in the medical world, is, hands down, difficult surgery. The window of success closes with each passing hour. Without blood flowing through the vessels, they begin to dry out and clot, leading to irreversible damage, Dr. Brady explained.

“Even in the best of circumstances, the success rate for something like this is maybe 20 percent, 30 percent,” Dr. Brady said, deeply emphasizing the “maybe” and ending his sentence with question-like intonation. In Mr. Jones’s case, the chance of a reattachment successfully working was estimated to be 12 to 15 percent, and the margin of error was absolutely zero, his surgeon said.

The patient looked into Dr. Brady’s eyes and implored him to do his best. He also promised he would quit smoking, cold turkey—which he did.

Fingers are most often chopped off in the workplace, Dr. Brady noted, particularly in the construction industry by builders and carpenters using high-powered cutting tools.

The surgery of replantation itself has changed little from its origins in the 1970s and 1980s, according to Dr. Brady. Yet it blends together some of the most technologically advanced aspects of medicine, including the use of clamps so small and delicate that they could be broken simply by laying them on the table, and some of the most ancient—namely, leeches. One hundred eighty of the bloodsucking worms were used to safely suck the blood out of the reattached part, two and three at a time.

After his repaired finger turned from a ghastly white to a promising pink, it later turned purple, an indication that blood was pooling and needed to be removed, post haste.

“With a replantation out this far [on the finger], the artery is tiny, the veins are impossible to fix at that level,” Dr. Brady said. “So what do you do? You’ve got blood flowing into the piece, but blood can’t get out of the piece, and that can kill the piece also.”

Dr. Brady ordered an emergency shipment of leeches. Fortunately for Long Island residents, the only supplier of medical leeches in the United States is in Nassau County.

After a brutalizing session of bloodsucking, the blood level in Mr. Jones’s body dropped to 75 percent of what it should be. Because of his age, 35, and health, however, he was able to tolerate it.

As hard as the surgery itself was, keeping the amputated piece alive was a critical part of the battle, and that’s where the emergency leech team played a role. In addition to Dr. Brady’s work, a team of round-the-clock nurses and anesthesiologist Dr. Scott Silverberg, who placed a catheter of local anesthesia near Mr. Jones’s clavicle, to dilate the vessels, scrambled to save the finger.

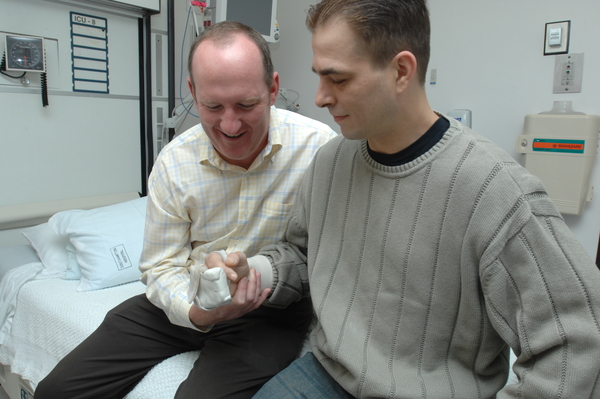

Mr. Jones, who celebrated his 36th birthday on Monday with his newly reattached finger, is full of gratitude for Dr. Brady.

“I’m very fortunate. Everybody thanks Dr. Brady, my whole family,” he said at the hospital on Friday, seated next to his doctor, whose eyes turned teary. “I need my hands as well as anybody else. I don’t have another career, so I will be going back to cutting meat. I still need to be able to hold a knife,” he said. At the other end of the table were his smiling fiancée, Debbie Chambers, 33, and his two youngest sons.

In order to maximize one’s chances of having a successful replantation after chopping off a digit, the key is not to panic, Dr. Brady said. In the moments after his accident, Mr. Jones grabbed the lopped-off piece and placed it in a box of ice—lucky for him, the ice-abundant seafood department was right near the meat department. He was rushed to the hospital by Bridgehampton Fire Department Ambulance.

It is best to save the finger by wrapping it in a moist paper towel, placing it in a bag and placing the bag on ice, Dr. Brady said. If it is put directly on ice, it can freeze and crystallize. And placing it in water can damage the tissues, as the human body contains saline.

Next up for Mr. Jones is another six to eight weeks of letting the replanted bone heal, followed by therapy to recover motion.

Mr. Jones attributed his mishap to being slightly out of proper position, which he said he will teach the younger butchers upon his return. He has picked up one lesson himself: “Go a little slower. Don’t be in such a rush, because you have eight hours in the day for your work. Whatever you don’t get done today will get done tomorrow. That’s the biggest lesson I’ve learned from this whole thing.”

Meanwhile, Dr. Brady is radiating with pride for his patient.

“Nothing makes me happier than to fix people and fix their problems,” the surgeon said. “But I couldn’t be optimistic with Carl, because I knew just how hard it was. And he looked at me and said, ‘Please try’—and I’ll remember that for the rest of my life.”