When he was a young actor in New York City, Steve Hamilton went to see a production of “April Snow” by Romulus Linney at a small, off-Broadway theater.

The two-character play featured a then-unknown Sarah Jessica Parker, but it was her counterpart who caught Hamilton’s attention.

As he watched Harris Yulin for the first time, Hamilton took note of his confident yet low-key stage presence, specifically his stillness.

“He was so still, so real and so deeply committed that it was astounding,” Hamilton said years later. “I had never seen him before, nor had I heard about him before that, so it was a revelation to me.”

This poise and commitment to his craft are some of the most remembered and revered qualities of Yulin, the longtime actor and director who died on Tuesday, June 10, from cardiac arrest in New York City. He was 87.

Born in Los Angeles in 1937, Yulin briefly attended the University of Southern California before enlisting in the U.S. Army. After living in Florence and Tel Aviv for short stints in the early 1960s, he returned stateside to pursue acting at the encouragement of his friends.

After finding acclaim on Broadway, Yulin went on to have a successful screen career and appeared in more than 100 movies and TV shows. A character actor known for playing “bad guys” and other unscrupulous characters, some of his most notable roles included corrupt cop Mel Bernstein in “Scarface,” Judge Stephen Wexler in “Ghostbusters II” and crime boss Jerome Balasco in “Frasier,” the latter of which earned him an Emmy nomination in 1996.

To most of the world, he was the bad guy. But to the East End, Yulin was a shining beacon in the theater community. A longtime resident of Bridgehampton with his wife, Kristen Lowman, it was impossible to talk about local theater and not mention Yulin’s name.

Josh Gladstone, the former artistic director of the John Drew Theater, now known as the Hilarie and Mitchell Morgan Theater, at Guild Hall in East Hampton, called Yulin “a great connecting point for so much of the significant theater work that’s been done on the East End for the last 20-plus years.”

Gladstone first met Yulin in the early 2000s and went on to work with Yulin on dozens of productions at Guild Hall, with Yulin both acting and directing. Initially, getting to work with Yulin was “at first imposing because he had a naturally regal presence.” But the more he worked with Yulin, the more Gladstone saw the lighter side of Yulin.

Kate Mueth, an actor and director at Guild Hall, noted that Yulin’s humor was “always low-key, it wasn’t like he was a guffawing type. He would just say things that were funny or sharp.”

One of the most common ways that those who worked with Yulin described him was as an “actor’s actor,” showing the ultimate sign of respect for his craft.

Gladstone said Yulin “was not a guy that overplayed, he was just a real, honest, truthful artist who was honoring the words and work of other artists.”

Gladstone pointed out Yulin’s sharp eye for reading scripts, while Mueth compared working with him to “sitting at a beautiful country wooden table” for his steadiness in an often-chaotic field.

“When you think about the theater, there are so many moving parts. It’s a tremendous feat,” Mueth explained. “And to have someone in the quieter parts and make it work, be functional and beautiful, is a feat.”

Yulin was also involved at Sag Harbor’s Bay Street Theater. His most notable role there came in 2018 when he portrayed former President Richard Nixon in “Frost/Nixon,” a dramatization of Nixon’s interviews with British journalist David Frost in 1977.

He received widespread acclaim for his performance, with Hamilton noting that Yulin’s performance stemmed from his commitment.

“He was able to inhabit Nixon without mimicking him,” he said. “He was drawing from experience of Richard Nixon from living in the ’60s and ’70s and not making a judgment about the character.”

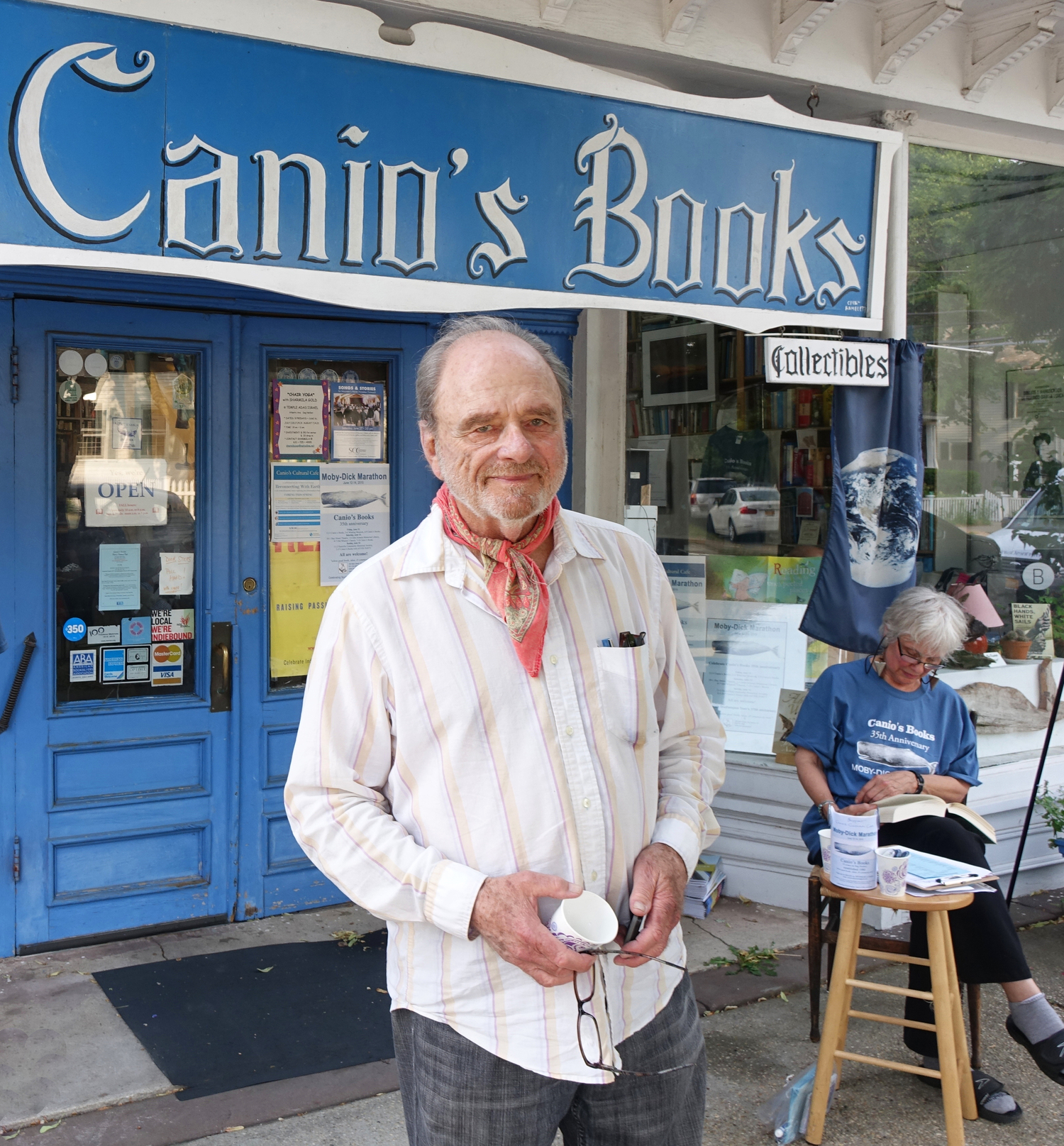

In addition to his work on stage, Yulin was a frequent visitor at Canio’s Books in Sag Harbor, where he would peruse the back shelves and regularly have wide-ranging conversations with those inside.

Starting in 2015, Yulin began participating in the shop’s annual Moby Dick Marathon, where attendees would read Herman Melville’s 1851 classic novel aloud. Yulin would read the part of Father Mapple and recite the extended sermon the character does at the New Bedford chapel.

Another local reading Yulin took part in was a marathon session last summer of John Steinbeck’s “Travels With Charley,” a travelogue focusing on Steinbeck’s 1960 cross-country road trip. Yulin read a chapter where Steinbeck met a traveling actor, a role that seemed perfect for him.

“He resonated with the spirit of an actor traveling and pursuing their craft, whether it be a small audience or a large stage,” said Canio’s Books co-owner Kathryn Szoka. “It kind of captured Harris’s sort of unique view of how to bring his craft to many people, not just people who can afford a Broadway ticket.”

Hamilton was also at the reading, where he sought advice from Yulin about his latest directing task, a production of “A Streetcar Named Desire” at Bay Street. Yulin recommended that Hamilton read Harold Clurman’s review of the 1951 film version, a gesture that resonated strongly with Hamilton.

“That really informed my thinking and plan for ‘Streetcar,’” Hamilton said. “His ability to lead you in one direction because he had such a clear sort of presence, such a clear integrity, because he was an artist at the theater, not just an actor.”

In his final East End theater performance before his death, Harris starred in “Scenes of Mirth and Marriage” at LTV Studios. The show featured Harris alongside Mercedes Ruehl, a longtime collaborator of his, as they performed scenes from various playwrights.

Yulin stayed busy up until his death as he prepared for a role in upcoming MGM+ show “American Classic.”

Two weeks before he died, Szoka spoke with Yulin and noted that his voice still sounded strong.

“He had an indomitable spirit that kept moving him forward,” she said. “I was happy to have a conversation with him, not realizing how near the end would be.”