Jim Witker vividly remembers the first time he attended a meeting of the Eastern Long Island chapter of the Korean War Veterans Association.

It was one week before the September 11 terrorist attacks, when he walked into Veterans Hall at the Southampton Arts Center. John McCarthy was the chapter president at the time, and a large crowd of more than 50 men were gathered together — so many, in fact, that they all wore name tags.

“That was the heyday,” Witker said.

A lot has changed since then.

Witker, who is now 91, is one of just three surviving members of the chapter, which will officially disband before the end of this month.

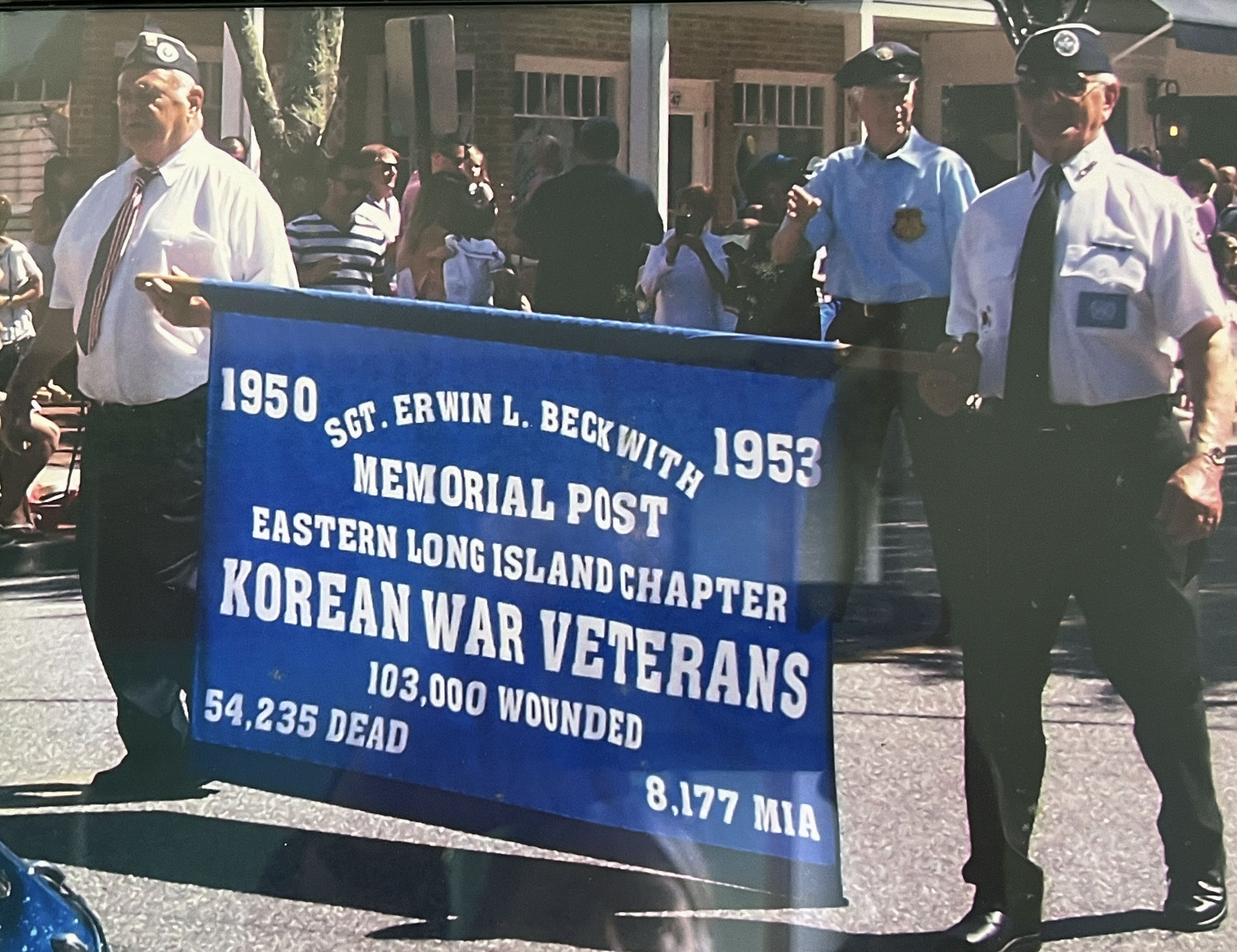

The Korean War began in June 1950, when soldiers from Russian-backed North Korea invaded South Korea, during the Cold War era. That July, American troops were sent to support South Korea. An armistice was reached between the two sides in July 1953, although it was not technically an official end to the war.

Despite the fact that roughly 5 million soldiers and civilians died during the conflict, the Korean War became known as “the Forgotten War” because it never received the same level of attention as World War II and the Vietnam War.

For those who either served in the military or were stationed on the Korean peninsula during the time of the war, contending with that legacy was difficult at times, and did not necessarily become easier after they returned from the war and carried on with their lives, embarking on careers and starting families.

It’s why veterans organizations are so key; they provide the opportunity to socialize, reminisce and build relationships with people who have gone through that struggle, and understand what it’s like.

Because time marches on, the organization is now down to three members: Southampton residents Stanley Penski and James Witker, and Sag Harbor resident Don Schreiber. Raymond Tureski, the most recent president of the chapter, died in September 2023.

Schreiber, 95, is in poor health and politely declined to be interviewed for this story, but both Penski and Witker shared their memories of what it was like to serve during the Korean War, and why the local veterans association was such an important part of their lives.

Tureski’s daughter, Elizabeth Tureski, spoke about her father’s devotion to the organization, the meticulous care and energy he put into keeping it running, making sure they continued having monthly meetings, even as membership dwindled steadily, right up until his death.

Of the group, Witker was the only one stationed in Korea during the conflict. Witker enlisted in the U.S. Army but because of his poor eyesight was not trained as an infantryman. Instead, he was trained as a combat medic.

He said he remembers his mother being “hysterical” about the prospect that he’d be sent to Korea.

“I kept trying to reassure her and saying that I’d be in a big hospital, just carrying bedpans for colonels, not in combat,” he said during an interview earlier this week.

When Witker arrived, he said he “still had hope” that he would not be in a combat zone. The truce had already been signed, so technically the fighting was over, but the reality on the ground was nowhere near as comforting as that sounded.

“That was simply a joke,” he said of the thought that the armistice meant that there was any kind of stability or peace. “There was still fighting going on every minute, along the demilitarized zone.”

Witker and his unit were taken north, across a river, and over to a series of huts right along the DMZ that made up the 44th Mobile Army Surgical Hospital — better known as a M.A.S.H. unit, the same kind that became the basis for the popular TV show starring Alan Alda that ran from 1972 to 1983.

Witker described his experience as markedly different from what was featured in the TV show.

“The first day I was there, the sergeant said, ‘You know the deal here, don’t you?’ and I said, ‘Deal? What deal?’ and he said, ‘Here’s the situation. We’re surrounded on three sides by the North Koreans, and the river we crossed and the bridge we came over on. If hostilities begin again — and that could happen any day, and at any moment — we’re going to be surrounded, and they’re going to blow up all the bridges.’”

The sergeant who delivered that sobering assessment of their situation added, “Keep your fingers crossed that nothing happens.”

Witker was treated to that speech on the first day of what would be 16 straight months there for him.

“Every day, we woke up wondering what was going to happen,” he said. “We were the front line medical station taking care of our own injured or sick or wounded. We had a few very bad sicknesses, like hemorrhagic fever, that guys were catching out in the field. We had a lot to cope with. We were very busy all the time.”

The men like Witker who were combat medics did not have any kind of extensive medical education or experience, aside from what was included in their training once they enlisted. Whitaker ended up becoming a training instructor, teaching his fellow troops how to handle cold weather equipment, repair diesel engines and more.

Everyone in the unit also had to take shifts walking armed overnight guard duty, which he said took a toll in terms of lost sleep and a constant thrum of anxiety.

“We were so shorthanded, and the infantry division we were supporting was also so shorthanded, so they couldn’t give us any guys to take care of our protection,” he said. Almost every other night, the combat medics like Witker would do whatever their jobs and tasks were during the day, and then sleep fitfully while on night duty.

“There were guys still getting killed by infiltrators and bandits,” Witker explained. “Our hospital was a target for robbers and bandits trying to steal our medicine and then sell it for a fortune. Every once in a while, we had to shoot at people coming our way.

“I still have a little PTSD after 70 years,” Witker added. “It rarely surfaces, but I do feel it every once in a while, even at 91.”

The long months working in tough conditions — cold weather, a frequent lack of running water, sleep deprivation — sleeping with his .45 revolver under his pillow, and the constant cloud of anxiety that hung over them because of their vulnerable position, and seeing people suffer, both their contemporaries in the military as well as Korean children and civilians, took a toll on Witker and the men he served with.

“It was very different from the TV show,” Witker said. “There were no pretty nurses, no martinis. We were too busy too cold and too scared, and it was too serious to have anything like that.”

Upon returning home, Witker said it was hard to adjust at first, and that he even briefly considered reenlisting. He eventually found his footing, but said he had some frustrating conversations with people after his return.

“What really upset me was that when I’d go out to a party, people would say, ‘Oh, you were in the Army in Korea? I didn’t know we still had troops there,’” he said. “People just basically started forgetting about the war. It was the placid 1950s — everybody was basically enjoying themselves. People didn’t want to think about boys dying and serving in foreign wars. So I found an indifference, if you want to call it that, wherever I went.”

That experience explains why being part of the Korean War Veterans chapter later in his life was so meaningful for Witker.

“I guess you could say it was like being back in the service, because you’re at the meetings, and getting together, and no matter what rank or branch of service or where you’d been stationed, we were all of the same generation,” he said. “Because of that there was a commonality, a camaraderie that reminded you of your military days. It was a special experience to be among guys that shared the same outlook. If you’re actually in a war and combat situation, it changed your view of life and of reality forever.

“It was kind of an escape to the past,” he added. “We all became good friends.”

Witker said he became close to Schreiber in particular, describing him as a “very funny guy.” “He’d come to the meetings and tell the most outrageously funny jokes,” he said.

Disbanding the chapter on November 16 will be bittersweet, Witker admitted, pointing out that what they’re experiencing is happening with Korean War Veteran organizations throughout the country. They plan to disperse their remaining funds to local charity organizations.

“Of course, we realized there was going to be a time,” he said. “Sometimes we’d make a joke and say, ‘The last one out has to turn out the lights.’”

The drop-off in membership became noticeably steep in the last seven or eight years, Witker said, but he gave credit to Tureski for doing an excellent job keeping it together right up until his death.

“He took the job very seriously,” Witker said. “He was a wonderful guy. He kept in touch with the VA, and any news bulletins they would have he’d share with us. He kept very good records and archives.”

Witker said the last order of business for the chapter before it officially disbands will be to rename it as the Raymond Tureski Chapter of the Korean War Veterans Association.

Tureski served during the Korean War, but was not on the ground in the peninsula during the conflict. He enlisted in the U.S. Navy with his best friend, John Kelly, when they were both still students at Southampton High School, in 1951, and was eventually assigned to the USS Saipan and became a skilled navigator, eventually steering the large aircraft carrier through the Suez Canal.

He saw the world during his four years of service on the ship, also traveling through the Panama Canal. He had a love for photography, and put together a scrapbook of his travels during his time in the service.

Tureski was the youngest of five boys, and they all served in the military. The oldest three served in World War II, and another in Vietnam. All of them survived.

“He loved his time with that chapter,” his daughter, Liz Tureski, said. “He was very close with Jim. They had a lot of similar interests in their life. It was also a fun thing for them to do, like being in the fire department. It was a social thing on top of that — it kept the guys going.”

Penski, who is now 92, enlisted in the U.S. Air Force in March 1950 and spent most of his time in the service in England, as a parachute rigger. He did not end up on the ground in Korea, but spoke fondly of his time in the service, remembering that he was in England during the time that King George died and during Queen Elizabeth’s coronation. He returned to the States in October 1953 where, he said, his future wife, Shirley, was waiting for him. They started a family, had five children, and now have several grandchildren and five great-grandchildren. They will celebrate their 70th wedding anniversary in June.

“I was one of the lucky ones who didn’t have to go [to Korea],” he said. “But if you have to go, you go where they tell you to go.”

These days, Witker, Schreiber and Penski don’t go very far from home. Witker struggles with arthritis, he said, and uses a walker. He has trouble with stairs. But in recent years, he tries to make regular outings for errands or simply to get out of the house for a bit.

Two years ago, he was at the Chase bank around the corner from his home on Cameron Street in Southampton Village. He’s a familiar face there, and often chats with the bank tellers. On that visit to the bank two years ago, he was approached by one of the tellers, who said there was someone who wanted to meet him.

“He called a young lady over, she was Korean-American, and he said, ‘Victoria would like to meet you, Mr. Witker,’” he said, recounting the experience. “She said, ‘My family and I will never be able to thank you guys enough. You guys saved my whole family from total death and destruction. I probably never would have been born if it wasn’t for you. You saved us — you saved the whole country.’

“I was so surprised, I didn’t know what to say,” Whitker continued. “I think I said, ‘You’re welcome.’

“As I walked out of the bank, I thought back to how, over the years, some of my old buddies in the M.A.S.H. used to say, was it really worth it, spending 16 months in this crazy and dangerous place, with all the fear and everything else? Sometimes people would say, it probably wasn’t worth 16 months of my life.

“Walking out of the bank, and coming down the steps, I said to myself, ‘Okay, Jim, was it worth it?’ I thought for a second and said, yeah, it was worth it.”