Joe Bartolotto began his career as a high school art teacher in the Sag Harbor School District in 1995. He has always been one of those teachers the students love, and not only because he teaches a subject that is fun and relatively stress-free, one that allows students to explore their creativity.

Over the years, he has been willing to have fun himself. Once he agreed to a bet with the field hockey team that if they defeated their longtime rival, and his high school alma mater, he’d dress up as a Pierson field hockey player. They won, and he did — complete with plaid kilt and wig.

He also shows a desire to connect with students. For example, he will often ask what music they are listening to, and take a listen himself.

Developing strong bonds with students by engaging in their interests and meeting them where they are has been one of his keys to success. But in the latter stages of his career, he’s found that increasingly harder to do, for a very specific reason: the pervasive presence of cellphones in schools, and, in particular, the way they’ve proven to be a powerful force causing distraction and disengagement for teenagers in so many vital aspects of their lives.

Constantly policing students and their cellphone use has become a frustrating and consistent everyday problem for teachers in middle schools and high schools — and even, sometimes, at elementary schools — across the country over the last decade-plus.

The East End has not been immune to that national trend. Districts have had to develop cellphone policies, and then it’s up to teachers and other faculty members to enforce them, with varying degrees of success.

Pierson as a Pioneer

The Sag Harbor School District took what could be considered a radical step this school year, becoming the first district in Suffolk County to ban access to cellphones while school is in session.

In March 2023, the district invited Andrew Richards, a representative from the company Yondr, to offer a presentation about the product his company offers at a Board of Education meeting. Yondr sells a patented cellphone pouch that locks when it is closed. The magnetic lock can only be unlocked by a small, handheld circular device similar to the mechanism used to remove security tags from clothing sold in retail stores.

Companies like Yondr have popped up in recent years to meet a demand for restricting access to cellphones at concerts, private parties and other events, as well as in schools and workplaces.

In schools it partners with, Yondr works with administrators to develop a plan and policy for implementing the pouch system, and then assists with other aspects of community engagement and implementation of the system.

Pierson Middle/High School Principal Brittany Carriero and Sag Harbor School Board member Jordana Sobey were involved in bringing the presentation to the board, and Carriero explained at that meeting that the district decided to reexamine its cellphone policy because the high school’s shared decision-making committee had become concerned about cellphone use in schools.

Sag Harbor administrators, teachers and parents expressed their support for the system, and it was implemented at the start of the current school year.

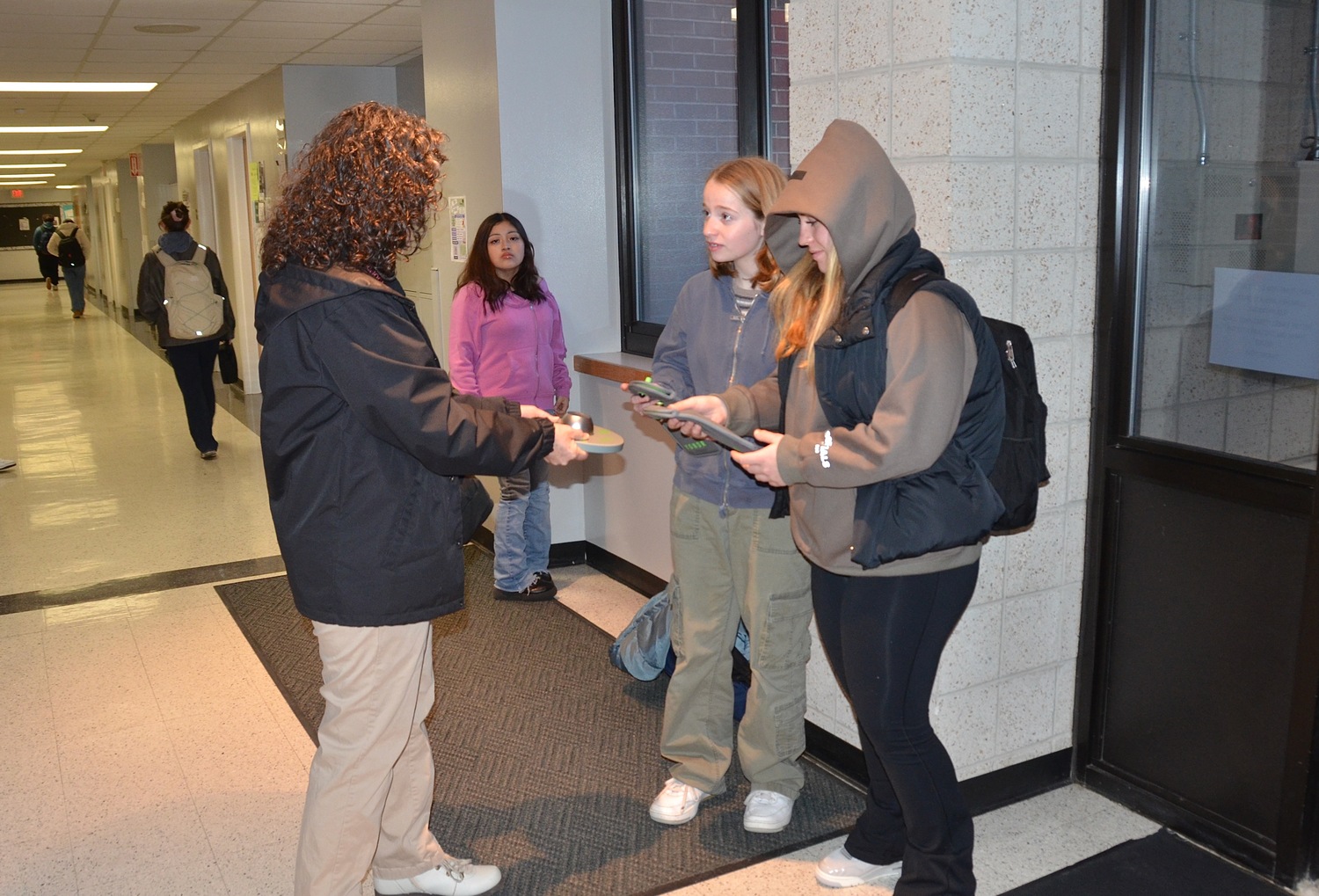

Now, every day when they arrive, middle and high school students are required to place their phones in Yondr pouches and have the pouch locked, under the guidance of staff — to ensure that they don’t find creative workarounds, like slipping a stick of deodorant or a dummy phone into the pouch in lieu of their real phone — and then report back to a faculty member again at dismissal to have their pouches unlocked.

Bartolotto is one of many teachers in the school who say they’ve seen a night-and-day difference in the school day since the arrival of the Yondr pouches.

“It’s reduced negative interactions with students by a ton,” Bartolotto said. “It’s tremendous. Now you’re not arguing with kids who are trying to post something on Snapchat or calling home because they forgot their cleats for a game. It’s been really great.”

The stress and frustration that accompanied constantly having to tell kids to put their phones away, or take their AirPods out, sending them down to the principal’s office for repeated infractions, having to repeatedly reprimand students for surreptitiously staring at the phone while giving a lesson or providing instruction — it’s been eliminated, Bartolotto said.

“It was just way too much,” he said. “I was always arguing with them. Now I don’t have to do that anymore.”

Varying Approaches

The implementation of the new system has made Pierson an outlier and a pioneer on the East End, and indeed in Suffolk County, when it comes to cellphone policies.

Sag Harbor is currently the only district in the county that has implemented the system, according to Kat Panayotov, Yondr’s education partnerships manager for New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania, as well as Latin America, although she said Yondr is currently in use in 3,000 schools worldwide.

A decade ago, the Westhampton Beach School District had a full ban on cellphone use in schools, although Superintendent of Schools Dr. Carolyn Probst said that in recent years the school updated the policy to allow for cellphone use in the hallways and cafeteria, but not in class.

“As cellphones became much more prevalent and more a part of everyone’s daily life, it felt a little draconian to tell a student to put the phone away everywhere,” she said, pointing out that vital communication goes on between students, their parents and their classmates when it comes to last-minute dismissal plan changes, making arrangements with a fellow student about an assignment, and other issues.

Probst added that there can be value in letting students have access to their phones for part of the day, mainly because it forces them to deal with the consequences of any negative outcomes that may result if they lack self-discipline.

“Some of what we have to work on, too, is preparing students to leave us and go out into the world, and they need to have some of those regulatory skills,” she said. “When you go to your job, if you’re busy and wasting time on your phone, not attending to your job will be a problem. So it’s about learning those regulatory measures of, I have to focus on something else.”

Hampton Bays Superintendent of Schools Lars Clemensen spoke about finding the happy medium between mitigating the negative effects of cellphone use at school and recognizing that smartphones continue to become further entwined in nearly every aspect of life — and often can be an effective tool with many different applications in many settings, even in schools.

“It has become an almost inseparable part of all of our lives, and students are no different,” he said. “So we have approached this by managing the what, when and how.

“There are apps and platforms out there, like EHallPass, that do require the use of a phone or tablet,” he added. “As the world becomes more digital and districts seek out solutions to make our lives more efficient, it does require that we keep this topic on the top of our mind. How do we integrate the use of technology, through a smartphone or other device, in a way that helps but also is still managed in a way to prevent issues that phone usage has sometimes caused in the past?”

It’s a question that will yield different answers and opinions depending on who’s being asked.

Thus far, reviews from administrators and staff at Pierson have not been mixed — they love the Yondr system and enthusiastically tout what they say are its many benefits and practically no drawbacks.

They say the feedback from parents has been mostly positive as well. And while they admit that the reviews from the students themselves vary, they are quick to add that any grumbling and complaining about the new policy quieted over time, as students adjusted to the new normal.

Differing Philosophies

Nicholas Dyno is the superintendent of schools for the Southampton School District, which, he said, has faced the same challenges and has had similar concerns as Pierson when it comes to student cellphone use. Like Pierson, Southampton adopted a new policy this year but took a different philosophical approach.

“Going back to when Sag Harbor made the decision, we were also struggling with cellphone use in the schools,” Dyno said in an interview last month. “It’s just become so overwhelming, with the desire of students who want their phones, with parents who want their students to have phones in case of emergencies, and then the need to not have students pay attention to their phones while we have teachers teaching and classes going on and content being delivered.

“But we looked at it a little bit differently,” he continued. “Our hope was to not remove the phones from the students, but our hope was to help make students more responsible with their phones. So we did develop a set of procedures and processes on cellphone use.”

Southampton’s policy states that “Cellphones and personal devices, inclusive of earbuds and headphones, are not allowed to be visible and/or heard in instructional spaces (all classrooms, the school library during regular school hours, and school assemblies). Students may use cellphones in the school only in noninstructional settings inclusive of lunch and study hall periods.”

“This is what guides the processes we’re using at the high school,” Dyno said of the new policy. “It tells kids what to do, it tells kids and parents what the disciplinary consequences are. All the teachers have bought into this, all staff have bought into this, all students are reminded of this, and we’ve seen a great impact of this, this school year.”

Dyno said that adopting a system like Yondr is “not on the table at this point” and shared his thoughts on the devices and the phone locking system.

“What I know of it, I think it can be a solution for some schools,” he said. “My worry is, in case of an extreme emergency, when parents want their kids to have the cellphones the most — and when we all believe kids should have their cellphones — to get them back into the hands of the student body in a quick and efficient way, while we’re worrying about emergencies, is what scares me.”

Dyno and the rest of the students, staff and parents got a taste of what that could feel like last fall during a districtwide bomb threat, forcing an evacuation and momentary chaos, fear and confusion.

It is the proverbial elephant in the room in the debate around whether students should have access to cellphones during school hours — the “God forbid” X factor.

Dyno does not have conflicted feelings about whether students should have access to their phones in an unexpected emergency situation, and he said the bomb threat, which turned out to be a hoax, was a learning experience, as well.

“It’s absolutely a good thing — and that’s what we learned from the scare we had last year, is that the students’ phones that were kept in pocket organizers in the front of each classroom, and then when the emergency dismissal happened and students weren’t allowed to retrieve them, we learned a lot from them,” he said.

“It put parents in a panic, it put students in a panic, and the two or three seconds to retrieve them on the way out of the classroom wouldn’t have made a horrific difference.

“And so now we’ve instituted that in our protocols to make sure they’re returned to students and to make sure that whenever we do collect them in an instructional space, it’s close access to the students, that they can have them in emergencies.

“So we did learn from that, thank God, that it’s something that we were able to modify in a quick way.”

Creating a ‘Present Community’

The situation Southampton navigated last year was, of course, a consideration for the Sag Harbor School District in discussions about whether to adopt the Yondr system.

Carriero said the local police department and other outside agencies have told the district that cellphones actually can be a distraction and impediment to executing protocols in the event of an emergency or lockdown scenario. “They’ve explained that having phones makes implementing the process when terrible things happen more challenging,” she said.

Carriero added that because the Yondr system allows students to still keep their phones with them while they’re inside the pouches, there are still ways to gain access to them by opening the pouch in an emergency measure, even without the device to unlock them.

Implementing the Yondr system in Sag Harbor was not simply about changing the cellphone policy, Carriero said. Rather, it was an intentional, proactive move that has more to do with creating a collective culture around cellphone use.

“We were trying to create a present community,” she said. “The kids can be present knowing that their phones are put away, and they’re able to have wholesome, deep, rich conversations instead of using an app on their phone.”

The benefits of the new system, the teachers and staff say, extend beyond the classroom.

Carriero and other teachers note that it has been refreshing to see students making eye contact with them and with each other at lunch, and when they walk down the hallways in between classes, instead of staring down at a tiny screen.

Discipline referrals related to phone use and social media in particular have plummeted, Carriero added. Mid-class bathroom breaks where students meet up and pore over their phones have gone down, as well.

“Kids are more instructionally focused,” she said.

As for concerns about communication barriers the new system could create, Carriero said the district is open to making exceptions for students who may have a medical reason for needing access to their phones. She also said that students are always welcome to use the landline in the office to reach a parent if they need to during the day. Bartolotto has a landline in his classroom that he allows students to use when necessary.

“We’ve never denied a kid who has needed to open their phone to reach a parent, or might have anxiety or concerns about plans for the day or anything like that,” she said.

Breaking the Cycle, And Looking Ahead

At Pierson, both Jaime Mott, the middle school librarian, and Sean Kelly, a high school social studies teacher, said the changes they’ve seen in students have been remarkable.

Last year, Mott would often watch students come to the library to meet up with friends, and they’d all be staring at their phones. Now, in those instances, she sees them sitting and talking to each other instead.

The students who come to the library to complete assignments seem to be having more success doing what they need to do now, she said, where formerly they’d often be sidetracked by their phones. “They’re able to focus better,” she said.

The new system has also resulted in a librarian’s dream.

“The kids are reading more,” she added.

Kelly, who teaches AP world history and U.S. history, said the students are now more engaged with him and with each other. And they’re simply spending more time in the classroom, as well, he said, estimating there’s been about a 90 percent dropoff in requests to go to the bathroom, go see the nurse, or get a drink of water during class.

It’s made for an overall healthier and more productive learning environment on many fronts.

“It’s one thing for the students to be more engaged with me,” he said. “As a teacher, it’s my job to find ways to make that happen regardless of distractions. But a key part of the learning experience is how well can you listen to what your peers are saying. That’s a whole aspect of teaching that I don’t have control over, but is extremely valuable.

“Whether in general class discussion or in groups, they seem to be alert to one another’s points of view. I see more dialogue between the students.”

Grades have also gone up this year for Kelly’s students, and while he can’t prove it, his sense is that it’s, at least in part, because of the new system.

“Rather than test scores, a metric I always use to measure student engagement is homework,” Kelly added. “Missed homework is way down.”

That factor, in particular, suggests that the long stretch of cellphone distraction-free hours the students at Pierson experience five days a week while they’re at school could have a sort of carryover effect at home.

Teachers have shared that in their conversations with students about the Yondr system, they experience a spectrum of reactions, and also mixed feelings.

“I would say there’s a small minority of students who really don’t like it,” Kelly said. “And other kids who would’ve been on their phone a lot but have adjusted.

“And there’s a third group that I think is even more fascinating, of kids who found out because of this policy that they didn’t really want to be on their phones as much as they thought they did. The policy kind of gave them a break and offered them the realization that there’s other things to do.

“Of that third group, I’ve had a lot of kids say, ‘I go on my phone a lot less than I used to.’ It’s breaking the cycle, or something like that.”

It also seems to have broken the cycle, or at least put the brakes on, the kind of trouble that keeps parents awake at night when they fret about their children’s cellphone use: social media.

Pierson guidance counselor Adam Mingione said student reactions to the new system have run the gamut, from outright disdain to mild annoyance, to a kind of casual indifference, but what he thinks is perhaps most valuable about it is how it has blunted the effects of bullying and negative interactions on social media, largely because it has provided a guardrail against a classic adolescent weakness — lack of impulse control.

“Phones give kids a tendency to want constant and instant interaction and reaction to things,” he said. “Now, if something happens in the morning, whereas in the past kids would be texting about it all day long, now they can’t do that. It lets things simmer down a bit. Whereas when they’re reacting all day long, they’re fanning the flames more.

“Now they can’t get to that until after school and maybe until after sports and activities, too, which causes even more of a delay. So maybe by the time they get home, whatever drama it was has already died down.”

One Sag Harbor parent of a seventh-grader, who asked not to be named, said the adoption of the Yondr system was why she decided to allow her child to have a cellphone for the first time this year.

“I was absolutely thrilled when they were even proposing [Yondr] as an option,” she said, adding she hopes it becomes a trend in other schools. “It was the only reason I got my child a phone. I originally wasn’t going to until eighth grade. When I said yes, it was because I knew it wouldn’t be accessible during the school day.”

She said she values the Yondr system for the positive impact it has on students on a social and emotional level, and said most parents she’s engaged with have been happy with the system, as well.

“The parents I directly engage with were thrilled,” she said. “I know that there’s a group of parents who don’t like it, because they want to be able to contact their kids at all times, but the parents I speak to absolutely love it. We have a hard enough time restricting access to the phones in general, so this one is out of our hands. Thanks, school!”

For the time being, it looks like the cellphone policies in place at school districts across the East End will remain the same, and Pierson will continue to be the only outlier when it comes to a radically different policy. The positive reviews from faculty and parents mean that Sag Harbor will stick with Yondr for the foreseeable future, without looking back.

With retirement in sight, Bartolotto has been doing some digging into the past, however, and in many ways, the implementation of Yondr has brought that on.

He recently found an old photo of an art class from the late 1990s, a bunch of his students posing for a photo. A handwritten sign he had posted on the walls listed several classroom rules in large letters, including one that shows just how much things have changed: “no beepers” was one of several restrictions listed as a classroom “law.”

Bartolotto is happy that his classroom is a phone- — and beeper-free — zone now, but said he’d be open to students bringing back one device he would allow in his classroom: a Walkman.

“That’s the only thing I wish we could bring back,” he said with a laugh, adding that listening to music has been helpful for students when creating art. “But I told the kids, send me a playlist, and as long as the songs are clean, I have no problem putting it on Spotify. I love being influenced by the music they listen to.”